Welcome to May streaming.

Lately, in the middle of my cinematic studies, I’ve been looking to the birds outside my window. As New York vacillates between sticky early summer humidity and the last chilly breezes of a snapshot spring, I’ve kept the living room window open, watching, with uncharacteristic focus, all the neighborhood birds flocking to our new, humble bird feeder, which sits snugly on the side of our fire escape. They’re vocal. They love Tori Amos. Recently, I found myself completely (and uncharacteristically) alone, sifting through endless film and television content during a temperate Golden Hour, when I made the revolutionary decision to turn off my tv set and simply watch the birds flit too-and-from in silence, taking in the minute sounds of their scurries. No movies… just me and the birds, and a big ole toke of “Neville’s Wreck.” Watching the glacial spectacle of reality, like reading for pleasure, is a muscle that I have to constantly train, particularly when I’m so often engrossed in the decadent pleasures of the moving image (“Reading is so cool. Have y’all heard about this?” I joked to my least judgmental girlfriends after picking up a $3 copy of Tess of the d'Urbervilles from the discount cart at the bookstore, which I read breathlessly and clutched to my chest deep into the evening like a long lost lover, images dancing on my eyelids). The first thing you delve into when studying any kind of moving image is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, when the shadows on the cave wall proved so fascinating to its inhabitants that they chose to stay in the cave and watch the illusion, rather than the real thing; it’s… a whole thing. Lately, I’ve opened my computer so many times to try and write about movies, too preoccupied with the bigness of current events and depressing realities of non-bird-related life, distracted by money, mania, and the lassitude that comes from trying to make manifest a passion project in a world increasingly hostile to activities and interests that don’t further the almighty dollar, Man’s true original sin. But no one wants to hear about that.

So I look to the birds and I try to get this newsletter out, even as days in May slip through my fingers and life seems to pass me by. It’s said that there are two types of people in this world: the ones who entertain, and the ones who observe. Only one gets paid the big bucks. The other’s just in it for the love of the game, and I’m suiting up. It just takes me a little longer sometimes.

This month, we’re packed to the rafters with these kind of thrilling sport metaphors, showcasing the cinematic iterations of two very different sports balls (how ‘bout those Knicks, huh?). Elsewhere: Gaslight Cinema, a (timely) May 4th-appropriate Actors Showcase, and a return to the well of progressive film. Put yourself in my hands…

What Lies Beneath: “Gaslight Cinema”

In the great graveyard where cultural critiques go after they’ve been beaten to death, “gaslight” is decomposing alongside other late Obama-era chestnuts like “mansplaining” and “radical self-care”: real, useful concepts that speak to the ways gender, class, (and race) are weaponized against vulnerable communities (on the macro and micro), which have since been plundered to whitewash all manner of poor interpersonal skills and selfish impulse through pacifying therapy speak. When Merriam Webster named “gaslighting” their “Word of the Year” at the end of 2022, it was the long-overdue death knell for a word wrung out by a culture determined to self-medicate (and absolve themselves of) their complex societal ills. As an avid watcher of the Real Housewives / Extended Bravo Universe, “gaslight”—along with several other therapy buzzwords like “triggered,” “boundaries,” and “toxic”—have been utterly co-opted to defend any number of outrageous actions or statements, both on unscripted reality programming and within the culture at large. Your “inner child” wasn’t “wounded” when you called someone a “stupid bitch,” your “inner child” needs to stop mixing amphetamines with Casamigos Reposado, you know?

Gaslighting, at least originally, spoke to a practice of psychological manipulation over a period of time meant to slowly destabilize the individual’s sense of reality and engender dependence on the perpetrator. Its a concept seemingly native to the medium of film: it’s thought to have been born with the classic 1944 film, Gaslight, in which Charles Boyer routinely turns down a home gaslight to drive his new wife, Ingrid Bergman, into a constant state of frenzy. The film is actually the second adaptation of a hit 1938 Patrick Hamilton play “Gas Light”: an earlier British version starring Anton Walbrook was buried by MGM, who demanded all negatives be destroyed to avoid competition with their star-studded Hollywood rendering of the same material (a common practice at the time, but luckily, they failed). Gaslighting became such a go-to cinematic concept because of its inherent physical association with manipulation of light: when the gaslight is on, we think we see things as they are, trusting the camera implicitly; when the perpetrator turns down the gaslight, casting darkness over proceedings, we aren’t so sure.

As a concept, gaslighting lends itself especially to the conventions of film noir: plays of lights and shadow, moral ambiguity, and a cynical worldview that everyone is ultimately in it for themselves. Men, of course, can be gaslit (we all love The Truman Show, don’t we folks?), but the best Classic Hollywood films feel almost proto-feminist in their presentation of systemic emotional abuse at the hands of emboldened men: movies like My Name is Julia Ross (1945), Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Dragonwyck (1946), Undercurrent (1946), Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), Whirlpool (1949), etc. derive tension in the inherent assumption that women (particularly working class women) are in possession of a comparatively limited amount of resources to escape their personal nightmare. It’s a classic film formula: is she crazy, or is she a victim? In a culture that still lobotomized, incarcerated, and otherwise pathologized “difficult” women, these mind games have potentially horrific consequences. Its a cinematic legacy that found particular relevance in neo-noir, psychological horror, and genre pastiche (Brian De Palma’s fetishistic Hitchcock tribute, Sisters, comes to immediate mind), particularly after second-wave feminism and the psychoanalytic-based analysis of feminist film critics of the 1970s, who (perhaps myopically) interrogated the allegedly patriarchal, predatory relationship between the camera and viewer. In contemporary film, it’s a go-to tool to depict stories of suspense and tales of domestic horror: modern gaslight classics like Flightplan (2005), The Forgotten (2004), and What Lies Beneath (2000) rely on the tension between a female protagonist and her own perception, particularly in the face of society’s indifference to her struggle (why else would all of those films star our very best middle-aged actresses)? There’s so many great films in this program (as well as Don’t Worry Darling), with so many different cinematic slight-of-hands and unique takes on what should be a well-worn cinematic concept at this point, but rarely fails to deliver. In this program, you’ll find Dubiously Real Wives who Disappear from Places like gas stations and hospitals, such as in The Breakdown (1997), Frantic (1988), and Fractured (2019); tales of systemic abuse propagated by shadowy entities in the service of cultural brainwashing, like Chinatown (1974), Orson Welles’ The Trial (1962), Oldboy (2003), and Michael Bay’s The Island (2005), a film I may gaslight you into enjoying; Movies Where Men Are Gaslit, Which Is Still Bad, Of Course; and a full-throated defense of mother! (2017). Have you gone mad, my reader? Or is it I who am mad?

And I Don’t Know’s on Third: Baseball Movies

“Baseball, Ray.”

They say that if you build it, they will come, but when it comes to baseball movies, they should say if you film it, they will come, for how successfully the sport has been canonized on the medium! (Work with me here). You might think me ignorant to the ways of the athletically-inclined, just because I am not athletically-inclined, but I actually love America’s Pastime, and I weirdly love a sports movie. I once even took a class on the intersection of history and sports film, looking at the ways in which thorny historical issues backgrounding major sporting events are smoothly reworked into the crowd-pleasing fabric of the rousing sports movie adaptation (when a nameless black woman throws a foul ball back in 1992 baseball classic A League of Their Own, for example, its as much acknowledgement as it is dismissal that the groundbreaking All-American Girls Professional Baseball League excluded black women, several of whom played alongside men in the dying Negro Leagues instead). One of the oldest sports in the Americas, the rise of baseball coincided with the rise of film technologies (as well as vaudeville), making it our most cinematic contemporary sport (as well as our most musically-inclined by a country mile). With baseball, its simple: run the bases, hit the ball out of the park, score the most points. The umpires call the shots, the fans watch and try to catch the pop flies, the organist hits the keys, and concessions sellers hawk wares to the delicious leitmotif of “Ice. Cold. BEER!” A charming scene, to be sure, though not always the most dynamic: how do you turn a sport that’s infamously a little slow to watch into a compelling feature film? Add comedy? Add sex? Add a monkey (as two films in this program, Ed, and Mr. Go, do)? Ghosts?? In honor of Baseball Season, and at the suggestion of my father-in-law, I’ve rounded up a close-to definitive list of baseball cinema, from the pinstripe sheen of Angels in the Outfield (1951/1994) and Field of Dreams (1989) to minor league gems like The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976) and John Sayles’ “Black Sox Scandal” dramatization, Eight Men Out (1988), to international interpretations of the sport from Japan (Takeshi Kitano’s Boiling Point) and South Korea (Baseball Girl), cultures who have their own unique interpretations of a game largely represented as Authentically American. At The Ballpark in Arlington (RIP), where I once watched my beloved Texas Rangers play (which was also the filming location for Dennis Quaid’s 2002 not-quite-family-baseball-classic The Rookie), the park would play the stirring final theme from The Natural every time the Rangers hit a home run, alongside fireworks, transforming the mundane patter of baseball into the truly cinematic. I have no real love for The Natural (1984), if truth be told, but when that theme song dropped in a ballpark environment, I was on my toes, tears in my eyes, hands raised in exultation at what Susan Sarandon calls “the Church of Baseball” in Bull Durham (did you know that there are 108 beads in a Catholic rosary and there are 108 stitches in a baseball?). Maybe it’s just the magic of Church of Baseball (Cinema). That’s the thing about movies: they transport us, involuntarily, to places we haven’t been before (like athletic success for yours truly), and we don’t ever come back exactly the same. We can’t ever really forget those shadows on the cave wall.

Let’s Play a Love Game: Tennis on Film

From the most accomplished cinematic sport to the least, building a list of Tennis Cinema1 was considerably harder than building a list of Baseball Cinema, but what’s a girl to do when the sports film on everyone’s lips is an entry into the former? At the end of last month, I said “nah-nah-nah-come on” to my husband, his high school best friend, and my best girlfriend, to form a little quad and see Challengers (2024), Luca Guadagnino’s latest contribution to the Gay Agenda, on opening night; I left it senselessly muttering “yeah, yeah, yeah, ye-ye, yeah, yeah, ye-ye, yeah” on repeat. A loaded little tennis film about a love triangle between Zendaya and two talented twinks that extends in every direction (talk about Canadian doubles), Challengers is probably already the greatest outright tennis movie of all time, not that that’s a particularly high bar to clear: if baseball is the ultimate cinematic sport, than tennis might be its anemic opposite. People can sneer at the flashy visual tricks Guadagnino employs in the film (which, if you haven’t seen it yet, what’s stopping you?), but you have to give him credit for playing with the visual language of a genre that’s woefully under-negotiated (to put it politely). Everything in life is sex, except tennis, which is sex, except tennis, which is sex, in Guadagnino’s Bull Durham, whose closest cinematic sister has to be Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), a tennis-adjacent movie adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s novel of the same name, about two queer-coded men who agree to swap murders (one of whom is played by Real Life Bisexual, Farley Granger). It’s one of several films in this program that employs the motif of tennis, rather than outright telling a tennis story. The ones that do tell a tennis story, like 2004 Kirsten Dunst vehicle Wimbledon,2 Billie King dramatizations When Billie Beat Bobby (2001) and Battle of the Sexes (2017), or Ida Lupino’s Mildred Pierce-esque melodrama Hard, Fast and Beautiful! (1951), are… less beloved than other sports films. We had a near-perfect tennis film, Match Point (2005),3 but considering it’s the movie that revitalized Woody Allen’s flatlining career in the 2000s and amounts to a rumination on the nature of mortal sin in the face of getting everything you want, it’s… a tough sell in 2024.

Whether in pairs or in doubles, tennis exists as a game of communication between player and opponent, trapped in a calculated observation of the other player, both physically (and mentally). It’s a fast-paced, invigorating sport that reads formulaic and repetitive onscreen, rarely bothering to depict the mental sport played alongside the physical. The best “tennis” movies employ tennis as a metaphor: in Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953), a “leisurely” game of tennis with Jacques Tati’s titular character ruins more than one vacationer’s holiday; in Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale (2005), tennis is the framework by which we come to understand a family’s collapse, illustrating how intra-family dynamics can take shape and alter perspectives; in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), tennis represents one character’s abject failure to succeed at anything at life, permanently trapped in a (deeply silly) uniform meant for a (let’s face it) deeply silly game. Respectfully! Game, set, match: this program looks at all the most interesting iterations of the sport of tennis on film.

It's not the years, honey; it's the mileage: The Cinematic Legacy of Harrison Ford

Oftentimes I find that I’ve passed a solid-to-revolutionary concept off to friends as having sprung fully formed from my brain like Athena, only to find that I actually just stole it from an old episode of Sex and the City I (probably) watched on E! (probably) sometime when I was unemployed. Such is the case with “yesterday, today, tomorrow,” a game I play with my girlfriends where we invoke our absolute ideals to whom we’ve sworn unyielding fealty: the people we were attracted to back then, are attracted to right now, and will be attracted to in the future. Think Dermot Mulroney, Tony Leung, Vincent Cassel, Michelle Pfeiffer, Juliette Binoche, Blair Underwood, or Pierce Brosnan (to name a few from our own collections). Our love is enduring, undulating with the waves of time even as the ravages of reality shape their famous visages and lessen our resolve to see their more mid-looking movies. Do you, citizen, know your friends’ yesterday, today, and tomorrows? Do you know your partner’s? Your own? How much can you know about yourself unless you understand what you find unassailably attractive (or unattractive)? There exists a special, elite pantheon of Actor that unites generations of movie fans across different eras: Robert Redford, Warren Beatty, Denzel Washington, Cary Grant. These are people who have been declared, cross-generationally, to be the absolute masculine ideals: actors whose charm and physical beauty have insulated them from standard considerations of value. And then there’s Harrison Ford.

How to summarize the body of work of Harrison Ford? Considering he’s one of my best girlfriend’s yesterday, today, and tomorrows, I feel considerable pressure to do him justice. A lanky, laconic hunk, Ford is the kind of knockout you only really begin to fully appreciate when you see how his irrepressible charm, signature Midwestern drawl, and boyish good looks come alive onscreen. Like Jesus Christ, he became a carpenter as a back-up job, only to fall into the orbit of George Lucas—unlike Jesus—through the efforts of legendary producer/casting director Fred Roos, who got him an audition for Lucas’ nostalgic classic American Graffiti (1973), eventually leading to his two signature film roles: Han Solo, cocky space smuggler, for Lucas; and Indiana Jones, cocky artifact wrangler, for Lucas’ buddy Steven Spielberg. In between those legendary screen characters, which would make him one of the definitive leading men to come out of the New Hollywood era, he appeared in some of the greatest films of the late 20th century, including The Conversation (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979) for Francis Ford Coppola, Blade Runner (1982) for Ridley Scott, and (my personal favorite) Mike Nichols’ Working Girl (1988), where he presented an entirely new blueprint for modern male masculinity (one not remotely threatened by a powerful woman in the workplace or the contradiction between physical beauty and business acumen). That’s the thing about Harrison Ford, and what makes him the leading man blueprint for a post-modern era: for all his bluster and eye-rolling onscreen, he’s not threatened by his leading ladies or the potential challenge they might represent. They’re his equals (and his sparring partners), and he engages them as such, even through the teasing and playful put-downs. He’s sexy, alternatively playful and severe, but never disposable, even in the small, throwaway parts he took at the start of his career before George Lucas Willy Wonka-d his life. As he matured into genre film roles in the 1990s and beyond, he never lost that uncanny ability to serve as audience conduit, snarking at the more ludicrous elements of a film’s construction without giving up the goat (though his love of returning to the wells that nourished him is not always reciprocated by viewers). It’s a formula oft copied, but rarely repeated, which you only really begin to appreciate when you observe others trying, and failing, to achieve the same alchemic magic (I think of Chris Pratt’s flat-lining attempts to copy/paste his acerbic leading man style in the Jurassic World movies, or Kevin Costner Going Full Asshole in Waterworld (1995), and how difficult a balance it is to strike for a performer without alienating the audience entirely). In his ass-kicking, Dad Cinema Panethon roles, like Air Force One (1997) or Witness (1985) or The Fugitive (1993), we buy Harrison Ford as both the exasperated everyman and the dude you want to call when you need someone to fly the plane (he is always prepared to fly the plane, whether the plane is prepared for it not). Well, what’s true in art is true in life: you need someone to fly the film? You call Harrison Ford.

The Carrie Fisher Extended Cinematic Universe (Redux)

When Carrie Fisher passed pre-maturely in Christmas of 2016, it hit me incredibly hard. The iconic nepotism kid-turned-sex symbol-turned acerbic Voice of the People was in the midst of a full career comeback, thanks to an expanding Star Wars sequel/prequel film universe: her mug was currently in theaters, super-imposed over a model in Rogue One, a final plea (“hope!”) rendered in plasticine-like surreality like a bizarre death mask4. The following year, she’d posthumously contribute her famous, real mug, and her famous, real words in Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi (2017), for which she wrote one of the film’s most stirring exchanges between herself (General Organa) and Laura Dern (Vice-Admiral Holdo), a tip-of-the-hat to her own legacy as a Genre Film Baddie:

So much loss… I can't take anymore.

Sure you can. You taught me how.

Back in 2020, when I first set out the seedlings that would become The Spread, The Carrie Fisher Extended Cinematic Universe was one of the first programs I ever put together: sure, I’m an unrepentant Star Wars fan, and sure, I love Debbie Reynolds—who, having appeared before me in Singin’ in the Rain (1952) so many times from an impressionable, pre-pubescent age, might as well be my own mother—and her complex relationship with her equally famous daughter. But more than that, I was stunned at the sheer extent of Fisher’s contributions to film. In addition to starring in a number of great (and not-so-great) feature films, Fisher worked for years as a Hollywood script doctor, punching up dialogue and developing female characters in potential masculine wastelands like Last Action Hero (1993) and Lethal Weapon 3 (1992), as well as low-key modern classics like Sister Act (1992), The River Wild (1994), and The Wedding Singer (1998). She even worked on Coyote Ugly (2000)! There’s a pace to Fisher’s patter that is so distinct, welding the showmanship of her Hollywood Lineage with the kind of acerbic talent for observation that comes with having seen far too much, far too young, in La La Land. She may have stood in the shadow of (first) her famous mother and (then) Princess Leia, which contributed to her own body dysmorphia, struggles with addiction, and larger existential crisis, but she had the best sense of humor about it. Her foibles, failures, and follies are somehow her most attractive quality (that radical honesty!), candidly speaking on addiction (and later, her bipolar disorder diagnosis) when it was still fairly stigmatized for women, particularly from seemingly grade-A American Sweetheart Stock. Consider that the Betty Ford Center opened in 1982; Fisher published her memoir, Postcards from the Edge, which would go on to become a classic film, in 1987. Few could speak to the simultaneously crushing and mundane cycle of addiction like Fisher, her signature brand of self-deprecating humor feeling relatable, rather than insufferable: “I said I didn’t think I was a drug addict because I didn’t take any one drug,” as she explains in Postcards from the Edge. It’s that compelling mix of pedigreed beauty, comedic timing, and unvarnished candor that translates so memorably onscreen, in comedic performances like Soapdish (1991), Blues Brothers (1980), and Hannah and her Sisters (1986), as well as her groundbreaking performance as the Definitive Rom Com Best Friend in When Harry Met Sally (1989). “I’ve got the perfect guy,” she explains, optimistically, at lunch at the Boat House as she plots to set up Meg Ryan from her literal rolodex of eligible bachelors, dog-earring the cards of married men for future reference. “I don’t happen to find him attractive but you might. She doesn’t have a problem with chins.” Ladies and lads, do you have such a friend in your life? Give them a call.

From Shampoo (1975) to Rise of Skywalker (2019),5 this program looks back at all of the movies Fisher touched as performer and writer throughout her impressive career, including at least one television program she allegedly played at the end of parties to encourage people to leave.6 I’ve done a bit of punch-up on my own old work here, bringing all the insight and appreciation that comes from being a woman roughly the same age as Carrie when she published Postcards from the Edge (having accomplished far, far less). God bless all the beautiful, difficult, and creative women of this world, forever and always; you make life a hell of a lot more fun.

Leftist Cinema 2024

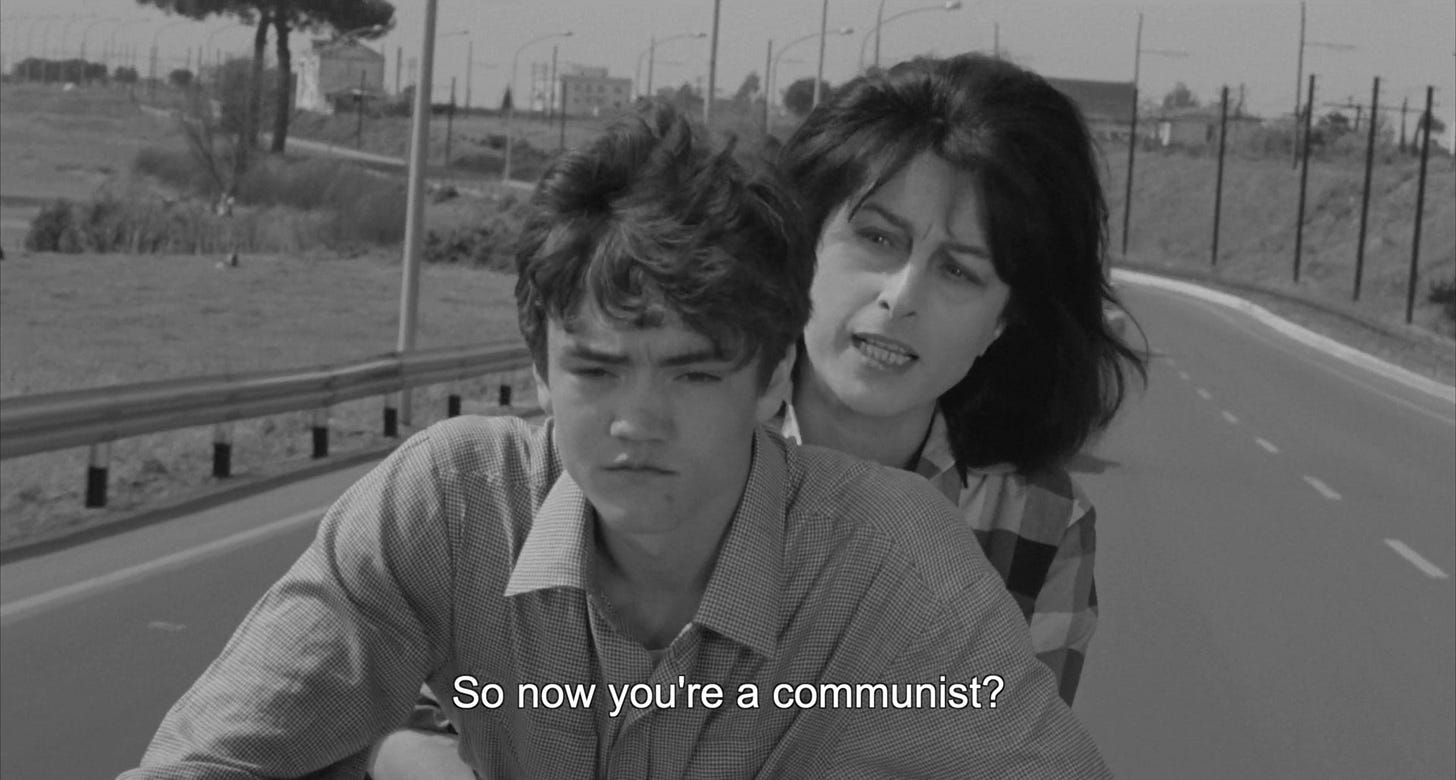

For the longest time, the popular adage went as follows: “if you’re not a liberal when you’re young, you have no heart; if you’re not conservative when you’re old, you have no brain.” Once you understand “the rules,” they say, you’ll see that, necessarily, there are winners and losers: and you don’t want to be the loser, so you better make sure you’re the winner. This past May Day, Vince and I joined students at our alma mater, New York University, in protest against the school’s crackdown on a student solidarity encampment built to challenge the school’s ties to Israel, an apartheid state. The students’ concerns include a satellite campus in Tel Aviv, which opened the fall after our own graduation, at which David Boies — the (then yet-to-be-disgraced) celebrity lawyer who, amongst other things, connected Harvey Weinstein with Mossad agents to spy on the producer’s many, many victims and suppress the New York Times article detailing his decades of abuse — was the commencement speaker. It’s a funny thing to find oneself over a decade older, standing in the footprints of the past, and still learning, long after graduation (only this time, a guy from a high rise tries to dump a bucket of water on your head). For these young people, it must be quite ironic to attend a prestigious university that sells itself as a safe space for dissent and discourse only to be censored, stifled, and punished over a seemingly arbitrary line in the sand (which happens to coincide with the hyper-specific interests of the State Department). A real lesson they wont soon forget! I kinda don’t think these kids, inheriting a world ravaged, carved up, and bled dry by greed, are going to become more conservative. (I remember when the Occupy Wall Street encampment, which went up our junior year of college, was viewed as a sideshow, rather than an era-defining act of political organizing). With each passing year—and it’s been three since we introduced this program—I grow more inspired by the young people who, facing the inequities of the world, dedicate their voices, proximity to city centers, and superior knees to the exhausting fight against global injustice. Each May, as we celebrate May 1st, International Workers’ Day, honoring the accomplishments of the international labor movement and the tireless fight for a better standard of living for all, The Spread returns to our repository of international leftist cinema: this year updates that ever-growing, 275-film list with new entries (including recent incendiary works like Jonathan Glazer’s Zone of Interest and buried 2022 indie gem How to Blow Up a Pipeline, as well as new-to-me films like coal miner strike drama Black Fury and anti-capitalist 80s western Walker), fresh write-ups, and all the latest streaming information. For me, film is (and always has been) a gateway to other cultures, a tool for education, and a complicated, conflicted medium simultaneously governed by capital and yet rebellious in the face of those limitations. Film is older than the five day work week; from the very beginning, radicals have taken advantage of the relative ease of production and distribution, and the wide-ranging creative possibilities of the medium to disrupt convention, promote empathy, articulate social inequality, and reach audiences that might otherwise lack access to (or interest in) ideas that challenge us to eradicate concentrated wealth and entrenched inequality. I’d be a poor former student of film, and a poor former student of NYU’s Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, to fail to regularly honor the medium’s progressive history and the role it’s played in pushing against the institutions that silence our yearning for a better world.

It is we must answer and hasten, and open wide the door

For the rich man's hurrying terror, and the slow-foot hope of the poor.

Yea, the voiceless wrath of the wretched, and their unlearned discontent,

We must give it voice and wisdom till the waiting-tide be spent.

Come, then, since all things call us, the living and the dead,

And o'er the weltering tangle a glimmering light is shed.

A theory proved by the mess of pre-film programming at Nitehawk.

Belongs to that strange moment in time where Paul Bettany got a shot at leading man roles, with James McAvoy (!) as “supportive best friend.”

“If you haven’t been merchandised for the last 30-plus years you haven’t lived,” Fisher jokes in Wishful Drinking. “Now among George’s many possessions, the man owns my likeness. So every time I look in a mirror I have to send him a couple of bucks.”

Although considered Fisher’s final film, released after her death, please note that her final film is actually the Rita Ora-starring vehicle, Wonderwell, which finally (allegedly) came out the summer of last year (?) after languishing for seven years in development hell without distribution. I think Carrie would have found the situation so very funny.