Welcome to July streaming.

As I often admit in moments of considerable inebriation, I have reluctant respect, like any 20th century lefty, for Richard Nixon, that great villain and boogeyman of late stage capitalism, whose paranoia and poor likability sunk his presidency as much as the myriad of crimes he committed while in office, including surveillance of his political enemies, which ultimately led to him resigning in disgrace. Gerald Ford, who was sort of the Republicans’ version of Joe Biden (he was best known for falling down), pardoned Nixon of all crimes in September of 1974, though Dick’s reputation was forever tarnished as one of our worst presidents; ironic, because in terms of Machiavellian Republicans, he was sort of the blueprint, a master of evil strategies and machinations, unlike the political figureheads to follow. I can’t help but think of Richard Nixon—and his favorite movie, Patton (1970)—as we approach this 4th of July, particularly now that the Supreme Court, in a sort of “mask-off” move, has upheld presidential immunity for “official acts,” something that ol’ Tricky Dick really could have used in his time (I know he’s howling from the bowels of hell). It makes for an interesting (and clear-eyed) Independence Day weekend, and we’ve got the pitch-perfect programming to meet the occasion, including Patton (1970) and Oliver Stone’s Richard Nixon biopic, Nixon (1995); both such terrifyingly relevant watches.

Elsewhere, it’s so confusing sometimes to be a girl (girl, girl, girl, girl), and who knew that better than Elizabeth Taylor? Let’s dive in…

Folks Inherit Star-Spangled Eyes: Americana in the Movies

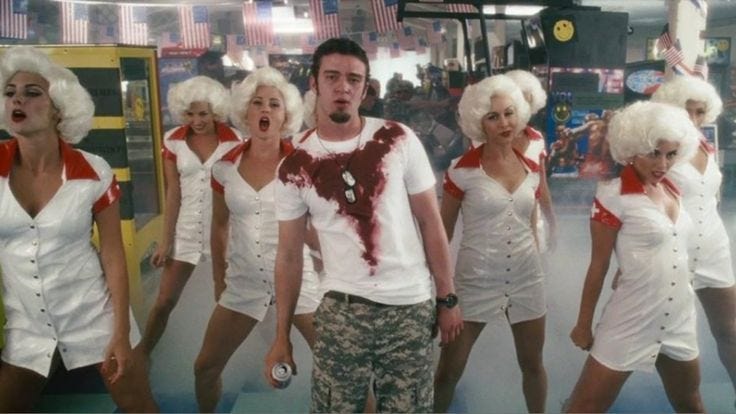

Oh sure, one little collapse of democracy and nobody wants to “be young, be dope, be proud, like an American” anymore. But here at The Spread HQ, for as much we mock the red, white, and blue 24/7, 365 days a year, we love America. Well, we love movies about America; they’re the best movies! Just in time for the disintegration of the checks and balances system that we’ve long been told is so indefatigable—and foundational to our democracy—at the hands of “nine oracles,” as my girl Nicole termed them, we’ve got a terrific program full of films employing American iconography, from propaganda to near-seditious filmmaking, and interrogating American culture, history, and mythology. Beat the heat this July 4th with a keen, critical eye for some of the most patriotic movies in American film history—Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), 1776 (1972), and Independence Day (1996)—alongside full-throated critiques of America’s cruelty, corruption, theocratic leanings, disregard for civil liberties, and war crimes, with films like Easy Rider (1969), Blue Velvet (1986), The Thin Blue Line (1988), The Parallax View (1974), The Doom Generation (1995), and so much more. PLUS! The comedic stylings of patriotic satires like Southland Tales (2006), Team America: World Police (2004), Dick (1999), Small Soldiers (1998), and Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999). I have no solution to or pithy take on the extremely precarious position we find ourselves in as a nation; all I can say is that, personally speaking, watching older films—and seeing the diverse range of heartaches we’ve overcome throughout history—can help put these larger existential questions into a somewhat more manageable (if no less cynical) perspective.

Won’t Go to Bed ‘Til I’m Legally Wed: Good Girls on Film

Lately, I’ve been consumed by Netflix’s Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders: America’s Sweethearts, a sort of more-artistic reboot of the long-running CMT show Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders: Making the Team, which, for 15 years and 16 seasons, took curious viewers inside the intense audition process to join the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, one of the most iconic (and infamous) “cheerleading” squads in the NFL (in Texas, cheerleaders and precision dance teams are separate entities within the pageantry of amateur football; the DCC are more akin to the latter despite being called the former). Intended as a boost to (sentient toad) Jerry Jones’ family brand, which has developed the DCC into an internationally recognizable entity all its own, the Netflix series couldn’t conceal the bad vibes permeating the organization. All the series had to do to touch on the darkness inherent within is present things as they are, which, in 2024, is extremely retrograde: the women are still paid a pittance; have their bodies picked apart like slabs of meat (establishing whether the woman has the correct “torso length” to wear the DCC hot pants is, apparently, part of the audition process); are routinely sexually harassed; and are forced to don a uniform that’s so skimpy and unforgiving, it has to be one of the last bastions of pure “tits and ass” entertainment in a post-Hooters world.1 The women themselves are so lovely: sweet, hard-working, passionate, dedicated, and intelligent (most work part or full-time jobs in addition to dancing for the Cowboys, a multi-billion dollar brand, illustrating just how little money they actually make). It’s impossible not to root for them, and their drive, when they hit those high kicks and jump into the famous splits during “Thunderstruck.” The team’s infamous “rule book,” allegedly over a hundred pages long at one point, included—at least according to the docuseries—the baffling line, “Have you ever had bad experiences with men? There is one acceptable answer here: as a cheerleader, no.” In 2015, when four Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders accused then-senior vice president for public relations and communications, Richard Dalrymple, of watching and recording them undressing,2 the incident wasn’t even prosecuted (owing to “lack of evidence,” an eerie echo of a similar incident that unfurls between a cheerleader and a sideline photographer in the Netflix series)… the man wasn’t even fired from his job—he “retired” six years after the organization paid a $2.4 million settlement to the women in question. Discussing their role as community ambassadors, the girls repeatedly mention the fact that they are representing a lucrative brand, unable to do anything to “disgrace the star.” It’s a triggering look straight back into the world of docile femininity, rape culture, and moral puritanism specific to Texas that messed me up five ways to Sunday: disordered eating, oppressive feelings of guilt and subsequent low self-esteem, weaponized white womanhood, and the systemic masking of messy, dirty feelings with a smile and a dismissive wave. Yes ma’am. No ma’am. Thank you ma’am. Being a “good girl” is a path paved with darkness and sublimation and self-inflicted punishment; it’s hardly a neutral process for the young woman involved. Good for whom? And for what purpose? This program unpacks these very themes of self-regulation, fractured morality, and malfunctioning good girls. “As a girl you see the world like a giant candy store,” Jennifer Aniston reflects in The Good Girl (2002). “But one day, you look around and see a prison.” In Splendor in the Grass (1961), Natalie Wood’s steadfast abstinence fractures her in half, driving her into hysterics. “I'm a good little girl, mom! A good little, good little, good little, good little girl!”

In Dirty Dancing (1987), Jennifer Gray’s self-actualization comes about at the realization that her Liberal father has class prejudices too, and that his adoration of his daughter is dependent on her chastity. In films like Carrie (1976), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), Black Swan (2010), and Perfect Blue (1997), the weight of purity culture and infantilized girlhood culminates in violent ends. Plus: the purity wars of the 2000s, the Go Ask Alice (1973) phenomenon, and the time a Gidget sequel sent me into a panic spiral.

A Real Bad Girl Throws Bleach: Bad Girls on Film

“Live fast, die young, bad girls do it well,” M.I.A, a straight-up bad person, once sang on the iconic 2011 track that—at one moment in time—felt like the soundtrack for a whole generation contained in a single song (“I heard that you like the bad girls, honey, is that true?” a woman sang on another seminal track from 2011). It was in heavy rotation at the time, when we felt young, wild, and free, sticking our tits up, drinking all night, screaming along to electropop, and posing in mirrors with digital cameras, unburdened by our own future struggles and the seismic political losses to come, including the eradication of female bodily autonomy by the very same judicial body who just ruled that when the president does something, that means it is not illegal. In a fantastic bit of synergy, M.I.A.’s track was featured on the trailer for Season 9, aka the best season, of groundbreaking Oxygen reality show, Bad Girls Club, which, beginning in 2006, showcased unapologetic, oversexed, aggressive, brawling, and generally misbehaving young women tasked with living in a house together. I began watching the show last year and fell in love with its (oddly subversive) approximation of “bad” behavior in the late-aughts, which ran the gamut from confidence to cruelty to sexual liberation (including a number of openly gay young women and participants on the Playboy circuit). It’s what first got me thinking about the thematic concept of “bad girls”—and, naturally, plotting a “bad girl” movie program.

Growing up, no young girl consciously yearns to be on the “bad” end of the Madonna / Whore spectrum that strictly governs the behavior and appearance of women; it’s a designation assigned, usually at a young age, alongside accusations that a girl, before she even understands what the words really mean, is deemed “fast,” “loose,” “defiant,” or “difficult,” usually in an attempt to excuse her own exploitation. More and more, women, like myself, are reaching adulthood before learning that they have undiagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders that make functioning extremely, exceedingly difficult; per CBS, a recent study found that the percentage of adult women newly diagnosed with ADHD practically doubled from 2020 to 2022. Experts speculate that these women were never diagnosed in adolescence, like their male counterparts, because their behavior never presented as “disruptive.” So many of the “bad” behaviors I assumed were part of my own corrupted soul, shoved deep into the darkest caverns of my heart, may have been nothing more than poor impulse control, emotional dysregulation, intrusive thoughts, and flightiness caused by inattention directly stemming from my ADHD. Young girls’ behavior is so heavily scrutinized and essentialized from such a young age that embracing the “bad” end of the girlhood dichotomy feels like the only liberating step to shed the crushing weight of society’s expectations and scrutiny. We learn through consumption, and it’s obvious to anyone that cinematic “bad” girls have more fun. When Sandy finally, finally teases her hair out at the end of Grease (1978); when Sharon Stone tears through sleazy men with an ice pick in Basic Instinct (1992); when Dorothy Dandridge and Beyoncé take on the role of 19th century Bad Girl Carmen in Carmen Jones (1954) and Carmen: a Hip Hopera (2001) respectively; when Rita Hayworth bumps and grinds to “Put the Blame on Mame” to the fury of the mean, ugly man who loves her in Gilda (1946); when Mae West tells Cary Grant,“When I’m good, I’m very good, but when I’m bad, I’m better” in I’m No Angel (1932)… these are the women we’re warned against becoming, who make it look so damn fun. Take a walk on the wild side with femme fatales, fallen women, murderers (“what murdaaaaaa”), bunny boilers, teen Queen Bees, and riot grrrls.

Real Eyes Realize Real Lies: Elizabeth Taylor, the First Modern Movie Star

If any one woman understood how nebulous the transition from “good girl” to “bad” can be in the public eye, it was Elizabeth Taylor: a once-beloved child star, capturing the nation’s hearts with Lassie movies and teen horse girl classic, National Velvet (1944), the ferociously talented (and achingly beautiful) actress led a wild, loud life, without apology, all the while appearing in some of the biggest films of the post-War era in the process. A product of the studio system, she later survived its collapse, making her one of the few stars to bridge the two disparate systems of celebrity. After causing the biggest scandal in mid-twentieth century Hollywood by stealing Debbie Reynolds’ husband, Eddie Fisher, the best friend of her late third husband, Mike Todd, who died in a plane crash just a year into their marriage, Taylor iconically broke up her fourth marriage (to Fisher) by conducting a torrid affair with her (married) co-star Richard Burton on the set of their 1961 epic costume spectacle, Cleopatra, a film so gargantuan and plagued with issues that it almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox. For her offscreen actions, Elizabeth Taylor was condemned by the Vatican, who derided her “erotic vagrancy” in an open letter; in 2011, the very same body publicly mourned her death as the “last remaining star in the firmament of old Hollywood.” That’s star power. Through illnesses, acts of god, scandalous affairs, booze, pills, weight gain, personal loss, postpartum depression, a waning career, and so much more, Elizabeth Taylor taught a nation of woman how to suffer the slings and arrows of life in style: unapologetically. From her late-era caftans; the infamous 68 carat Cartier diamond, later dubbed the “Taylor–Burton Diamond,” which once festooned her neck; to the turbans, cigarette holders, and furs that made her an international style icon in the 1960s and the bouffant hairstyle that only got bigger and darker with old age… Elizabeth Taylor was the most glamorous woman alive, and had the style on (and off) screen to match. After transitioning (quite young3) from teenagers into adult roles in iconic films like Father of the Bride (1950) and A Place in the Sun (1951), she relished the chance to showcase her effervescent screen charisma (and gorgeous violet eyes) in more mature projects like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), spending the film in a series of slips and form-fitting clothes, cooing at her gay husband while prattling on in an arch southern accent. Her off-and-on romance throughout the 1960s and 70s with the hard-drinking Burton (which included two separate marriages) fueled a jet-setting lifestyle that made them reliable tabloid fodder and messy co-stars in a handful of bad-to-great films, including their fearless collaboration in Mike Nichols’ 1967 adaptation of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, in which they embodied George and Martha (“sad, sad, sad”), two broken, embittered people who can only exist within each other’s orbit, playing sick drinking games to dull their painful, fraught coexistence (“you can stand it, you married me for it!”). Taylor, who gained weight and ratted her hair frizzy for her performance, won her second Academy Award for the braying, beguiling Martha; her first, for the dreadful BUtterfield 8 (1960), rewarded the actress for playing a sex worker at a time when most big name actresses would balk at such a role, particularly given her off-screen infamy in the late 1950s.

“From the age of 9, I began to see myself as two separate people: Elizabeth Taylor the person and Elizabeth Taylor the commodity. I saw the difference between my image and my real self. After all, I was a person before I was in films, and whatever the public thought of me, I knew who I really was. Even at that young age I decided that my responsibility to the public began and ended with what I did before the camera.” - Elizabeth Taylor

She was always doing that: playing messy, loud, and/or defiant women onscreen, such as her proto-feminist turn in George Stevens’ Texas epic Giant (1956), where she openly defies the oppressive, patriarchal attitudes carried by the locals, including her own ranch-owning husband, played by Rock Hudson, who became a lifelong friend. When Hudson disclosed his HIV positive status in 1984, making him one of the first big name celebrities to do so, Elizabeth Taylor, despite fear-mongering attitudes of the time, visited him in the hospital, publicly stood by his side, and even organized his memorial following his death the following year. She committed herself to HIV/AIDS activism in the years following, co-founding the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) the same year of his passing; in 1991, she founded the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, which still works to assist those living with HIV and AIDS. Her status as a gay icon was not achieved lightly: she befriended a number of queer men throughout her Hollywood tenure, including James Dean and Montgomery Clift, never disclosing the true nature of their sexuality, and, in the case of the latter, literally physically shielding him from paparazzi and manually prying teeth out of his throat following a horrific motorcycle accident during the filming of Raintree County (1957).

Elizabeth Tayor was an easy punchline: too rich, too dragged up in old age, and utterly addicted to love, she was a woman who truly chased life, uncaring of anyone’s opinion. I’ve always thought it was fabulous, and a little inspiring, that she married a total of eight times (two of which were to the same person), and never stopped driving men crazy (including, never forget, Colin “I wanted to be number eight but we ran out of road” Farrell): never give up. Can you ensnare a young heartthrob 44 years your junior from your Cedars Sinai hospital bed? Didn’t think so.

That’s it for now! Stay young, dope, and proud this Cancer season and keep an eye out for more dispatches from The Spread. Times may be tough, but if you’re reading this, you’re as cool as the other side of the pillow… and isn’t that, ultimately, what matters?

I never wore the iconic Rangerette-influenced DCC uniform, though I did receive this (extremely haunted-looking) Dallas Cowboys’ Cheerleader doll from a family friend.

Per ESPN: “A Cowboys representative said the team thoroughly investigated both alleged incidents and found no wrongdoing by Dalrymple and no evidence that he took photos or video of the women. The team does not dispute that Dalrymple used his security key card access to enter the cheerleaders' locker room while the women were changing clothes.”

By 17, Elizabeth Taylor was playing teenage women coveted by grown men in films like A Date with Judy (1948) and Father of the Bride (1950) and it was—to say the least—weird. She later reflected: “At barely 17, I grew up for all America to see. I was cast in Conspirator [1949] opposite one of MGM’s biggest stars, Robert Taylor, who was 38, more than twice my age. In between playing passionate love scenes with a man old enough to be my father, I had to fit in three hours of lessons before 3 in the afternoon, otherwise production would be closed down for the day. I nearly went crazy. Some afternoons my teacher would walk out on the set, grab me out of Robert Taylor’s arms, and say, ‘Sorry, Elizabeth hasn’t finished her schoolwork.’ Talk about humiliating.” Taylor began the first of eight marriages in 1950, at age 18, when she married Nicky Hilton, son of hotelier Conrad Hilton, who was completely unable to cope with her celebrity and turned abusive; their marriage was dissolved just half a year after it was consecrated. Within a year, she was on to her second, to actor Michael Wilding, a man twenty years her senior. And we’re off to the races…