Welcome to September streaming.

With all eyes on Chicago last month for the Democratic National Convention, I too found myself attuned to the machinations of the Windy City: actually, I was in Chicago, but I wasn’t attending the political pageantry—the closest I came to the proceedings was blinking up at a muted Joe Biden from a television at the Green Mill, drowned out by live jazz. Fitting for the jaded cinephile: James Caan sits at the same bar-top when he learns that his money has been pinched in Michael Mann’s Thief (1981). “I come here to discuss a piece of business with you, and whadda you gonna do, you gonna tell me fairy tales?” he later asks the man responsible, a sentiment I felt keenly at seeing a party—my party—preach peace and tolerance at their biggest fête, only to end it by doubling down on the claim that Israel “has a right to defend itself,” a statement reiterated at last night’s presidential debate (not now, the party says, with the election on the line). At the Toronto International Film Festival last week, a group of protesters disrupted the opening night remarks to urge TIFF bigwigs to cut ties with the Royal Bank of Canada, a festival sponsor with investment in Palantir (a military and intelligence contractor that currently provides artificial intelligence technology systems to the IDF) to boos and dismissal from the crowd. The message was clear: not now, not now.

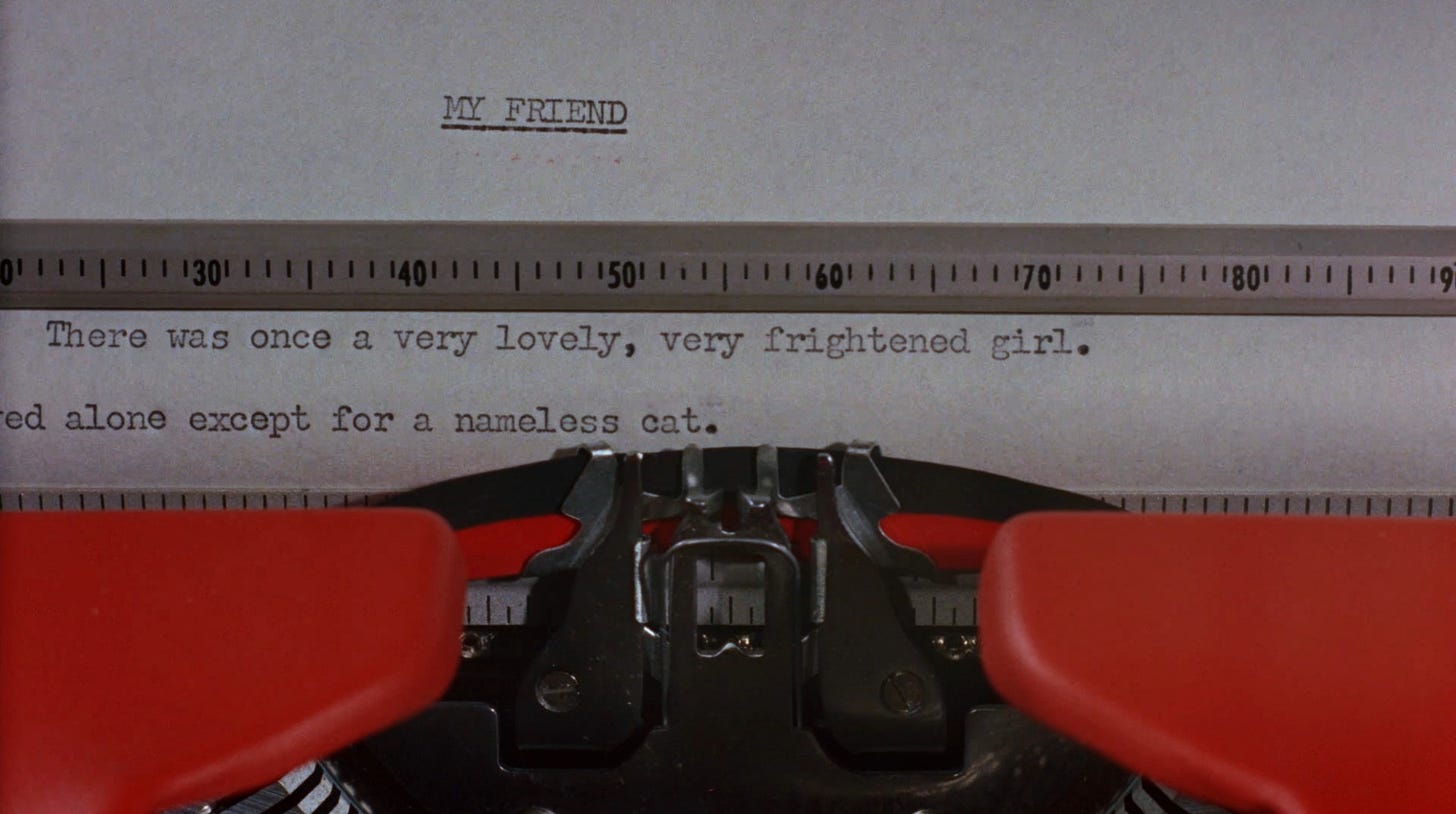

Despite fears echoed by pretty much every older Chicagoan we encountered, the week did not descend into the chaos of 1968—beautifully captured in Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), when a split election over the Democratic Party’s continuation of the Vietnam War drove protesters en masse to clash with police and the National Guard—though a slew of protesters did challenge the party’s line on Gaza, to far less fanfare. We did, however, take a trip to the American Writers Museum, an existential exercise considering my own persistent writer’s block. A station of working typewriters offered attendees the chance to type out missives of their own to pin to a wall of thought, and, faced with the chance to write something witty and original, hack that I am, all I could think of was a film reference: “There was once a very lonely, very frightened girl. She lived alone, except for a nameless cat.”

The lonely writer seems to free his mind at the movies this month, as we turn to films about writing, writers, the fickle pen, and the evasive muse that makes the practice so profoundly annoying. Then, we’re digging into onscreen nudity, dredging up messy, thorny topics surrounding cinematic taboos, bodily autonomy, exploitation, sexual expression, and censure. Finally, this month’s actor showcase honors an extremely classy, highbrow actor—to offset the lurid themes found throughout this month’s programming—who nevertheless found himself at the center of one of the most controversial films of all time. Let’s turn the page and begin, shall we?

The Day You [Watched] a Writer in the Dark: Writers on Film

“Do I have an original thought in my head?” Nicolas Cage, as screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, asks himself at the top of Adaptation (2002), Spike Jonze’s meta-film about Charlie Kaufman’s fraught attempts to adapt Susan Orlean’s non-fiction novel The Orchid Thief, which in turn became the basis for the film. As Kaufman, Cage hunches over a typewriter and looseleaf paper in his dingy, crowded home, growing bald and fat, missing whole beats of passing time, and wallowing in self-pity and feelings of inadequacy. So… he’s a writer, basically. It’s a film in my thoughts this month, alongside a few others, as I struggle, once more, to cobble together this newsletter. “Here is the story of my career… I make no apology for being egotistical.. because I am!” Judy Davis intones at the start of Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career (1979), in which a young female novelist sacrifices love and marriage to dedicate herself wholly to her creative pursuits. The Australian novelist who wrote the book that inspired Armstrong’s film was actually cursed by its popularity, finding only scorn from her family and community upon assumptions that it was autobiographical, and that she’d revealed their dirty secrets to an all-seeing world of readers. “I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live,” Anais Nin—whose likeness is featured in this program, courtesy Henry & June (1990)—wrote in her diaries. Our current world is ill-suited to support writing, or film; yet, for the writer, and the filmmaker, the compulsion to compose remains just the same.

Recently, I was named one of the emerging critics in this year’s Film at Lincoln Center Critics Academy, granting me press access to the New York Film Festival and fortifying my resolve after years of work developing this cinematic repository and my own critical voice… When the waves of imposter syndrome crest and crash over me, as they often do when I write this dispatch, I can wrap myself in that comfort: someone, somewhere, said I had something. Surely, there is no bigger curse — nor habitude more mortifying — than the compulsion to write. Time-consuming, frequently fruitless, alienating, and sedentary, the act of writing is as unpleasant as it necessary, feeling, most days, like an exorcism more than a passion: a ritual humiliation masquerading as expression. “There's no sacrifice too great for a chance at immortality,” Humphrey Bogart, a struggling screenwriter (and possible murderer), tells a passive waiter in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place (1950), hinting at the dark impulses that govern his id: it’s meant to caution, rather than inspire. The best films about writing speak to that insatiable drive to create and/or document that consumes and takes, with little reward: when newswoman Rosalind Russell completes a fantastical story, against all odds, at the end of His Girl Friday (1940), she sacrifices all her girlish dreams on the altar of her fast-paced, insatiable profession and her conniving, beguiling editor, who plays her own ambition against her. It’s… not a flattering portrait; most films in here are not. The program is full of ghoulish newspapermen, jaded screenwriters, hack novelists, disgraced plagiarists, and depressed ghost writers, as well as real-life, complex authors like Emile Zola, Colette, Henry Miller, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Truman Capote, The Shelleys, Oscar Wilde, Dorothy Parker, Hunter S. Thompson, and the Marquis De Sade, to name a few. I can’t help but find their creative toils and foibles… edifying at this time.

When confronted with the great insecurities and greater questions of life, I turn to the movies for guidance and solace. So here are films devoted to the act of writing, and to the figures, who, facing those great questions and uncertainties of life, committed them to paper, leaving behind a record of thought and opening themselves up to judgment for it. In my most vulnerable moments, I consider the cinematic encouragement—as inspiring as it is bittersweet—offered by River Phoenix to a young writer in Stand By Me (1986), the lead film in this program:

“It's like God gave you something, man… And He said, ‘This is what we got for ya, kid. Try not to lose it’.”

Breastivus for the Rest of Us: Building a Tit Cinema Canon

What is 20th century film culture without breasts?

This isn’t an attempt to be glib, but rather an attempt to unpack the role that female-presenting breasts have played in the formation, development, and refinement of American film history and culture. Roger Ebert, perhaps our most recognizable and beloved film critic, famously loved large breasts, and as the story goes, only went to go see a film called Faster Pussycat, Kill! Kill! (1965)1 because it very much foregrounded the considerable assets of its three gorgeous female stars. The experience was the kernel of what would become a fruitful critical (and later, creative) relationship with cult director Russ Meyer, with whom he’d write four films, including one polarizing, breast-centric Camp classic, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), which is now part of the Criterion Collection.

Hollywood, and America, runs on breasts: the structured, shapely silhouette of Mae West was so iconic, it leant a nickname to the famous “contour” Coca-Cola bottle; Hedy Lamarr’s infamous nude dip in Extase (1933), a Czech film noteworthy for its depiction of a female orgasm, brought her to the attention of Hollywood, later fueling a fight over censorship standards when the film attempted to play stateside;2 Claudette Colbert’s outrageous milk bath—which only just concealed her unbound chest—in Cecil B. Demille’s Sign of the Cross (1932) caused a cultural sensation; Howard Hughes, Hollywood producer and aerospace engineer, famously ordered the construction of a special bra to properly showcase the bust of Jane Russell in The Outlaw (1943), to the fury of the Production Code Administration, headed by staunch Catholic (and anti-sex advocate) Joseph Breen, a fight memorably dramatized in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (2004):

Yes, who doesn’t like tits? Breasts, boobs, melons, honkers, tatas, titties… memorable mammaries have driven the artistry of so many filmmakers in highbrow and lowbrow cinematic circles alike, yet can’t throw off their prurient reputation. Russ Meyer, that aforementioned maestro of titty flicks, was just one contributor to what Ebert once called “that uniquely American genre, the skin-flick.” Meyer’s brand of “nudie cuties,” which are heavily featured in this program, existed under part of a larger umbrella of sexploitation cinema, the proverbial wrapped-in-plastic-and-placed-behind-the-counter films of the American cinematic tradition that—while not revered—played an important role in the larger fight against film censorship. The push-pull between these historically-denigrated films (“nudie cuties,” but also stag films, “health” roadshow films that trafficked in casual nudity, and “grindhouse” exploitation films) and mainstream cinema epitomizes the fraught history of sex on American film and the fascinating way in which lowbrow art forms shaped, reformed, and transformed highbrow cinematic tradition: the transformation of American popular culture after the sexual revolution accompanied a concurrent rise of independent cinema, in a fruitful synergy that transformed both.

In 1963, Jayne Mansfield—a beautiful blonde bombshell known for her considerable bust—became the first mainstream American film star (of the sound era) to appear topless in a film: Promises, Promises (1963), an all-but forgotten sex comedy that was outright banned in several cities across the country. The film received simultaneous promotion in the pages of Playboy magazine with the nude photo spread “The Nude Jayne Mansfield,” which earned editor-in-chief Hugh Hefner an arrest charge for obscenity in Chicago. Of course, this was just the tip of the iceberg (fellow bombshell Mamie Van Doren scored her own pseudo-topless comedy, 3 Nuts in Search of a Bolt, just a year later) and ultimately, history sided with the perverts.

The explosion of the American independent film scene in the 1960s and 70s, spearheaded by the late Roger Corman, a lover of fostering young creative talent and showcasing beautiful, well-endowed women,3 ran parallel to the counterculture movement in the United States, which upended older ideals about sex, nudity, freedom, and censorship… a cultural precursor to the “porno chic” era of the early 1970s, in which pornographic film was consumed and discussed by well-heeled denizens of urban centers, and the lines between mainstream and pornographic film blurred significantly, with lasting cultural impact. You can’t close Pandora’s box, but censors still found a way: the enforcement of the MPAA ratings system, introduced in 1968, replaced the old, fallen Production code, allowing for the incorporation of nudity within film, but, theaters could also better regulate who had access to these films, particularly once the rise of home video tape separated sex-laden films to the safe sanctuary of home consumption. The introduction of the “NC-17” rating in 1989, designed to replace the dreaded “X,” so-often associated with hard pornography yet also applied to boundary-pushing art films, presented filmmakers with a new problem: films deemed “more explicit” by a shadowy governing body of random people (the MPAA) ran the risk of receiving the rating, which translated to box office poison. National theater chains and home video rental stores like Blockbuster wouldn’t even carry NC-17-rated films, kowtowing to prudish voices demanding censure.

Obviously, these roadblocks did not quell our cultural appetite for breasts, and sex comedies—like Porky’s (1981), Hardbodies (1984), Hot Dog…The Movie (1983), and Summer Job (1989)— begat a new American tradition of the flagrant exhibition of bared female bodies in irreverent films with dubious sexual politics. In our current post-fourth-wave feminist moment, we’ve become more culturally accepting of the notion that women should be allowed to exhibit (or conceal) their body on their own terms, without receiving harassment, abuse, or disenfranchisement as a result; we’re also more tolerant of bisexuality, understanding that women, as well as men, enjoy looking at women’s bodies. Yet we’re still woefully behind on a proper boob-centric film study, despite the significance it’s played within our national film culture (and the knowledge that programming a film does not mean an endorsement of its content nor its politics).

We relegate cinema particularly preoccupied with breasts—or the discussion of breasts on film—to the sleaziest possible corners of the internet, conducted by the worst possible people, most of whom are heterosexual men:4 Reddit, Mr. Skin, free porn sites, etc., handing them all the power. Recently, I found myself genuinely let down by a longtime Twitter mutual, “Sluts and Guts,” after they posted photos meant to shame a famous woman for her body—and I thought, with earnest disgust, “That’s not in keeping with the spirit of the exploitation film community,” to which I am undoubtedly a member. I see no contradiction here: naturally, the consumption of these films necessarily raises thorny issues of exploitation, slut-shaming, and industry harassment, all of which are conversations we should be having, not hiding from, particularly as they’ve led to the normalization of intimacy coordinators on sets.

As a well-endowed woman, for whom objectification was never really off the table, I find America’s double standard around female-presenting nudity particularly ridiculous: we are obsessed with breasts, yet denigrate them, relegating them to our sleaziest circles of appreciation. This moralizing falsely leads us to believe that bared breasts cannot be anything but an extension of non-consensual exploitation: that women cannot make decisions over their own bodies, and cannot be proud of their racks, which they’re told to conceal and regard with shame—the “the lie someone told you about yourself,” as Anaïs Nin once wrote.

Did I program this series just because I am a stacked, sex-positive, feminist female film critic, and I can get away with it? Hell yes!

Cock of the Walk: The “Full Monty” on Film

Is male-presenting full-frontal nudity film’s final taboo? Despite decades of evidence to the contrary, there’s just something about it that still manages to raise people’s ire (and fascination)… yet it’s rarely discussed in specifics as part of a larger conversation surrounding film censorship and cinematic exhibition of the male form. Mostly confined to gimmick, be it comedic or sexual, full-frontal male nudity is generally discussed on a film-by-film basis, and often with a vaguely infantilizing tone, as if the novelty of seeing a penis on screen means we have to discuss it like some dirty, forbidden secret, as if still confined to the proverbial playground. Nudity, obviously, serves far more creative purposes than mere titillation, yet we rarely stop to analyze the different context in which such male full-frontal nudity plays out, or what purpose such imagery serves, preferring to gossip about the genitals of the actors involved. In David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (2007), Viggo Mortensen’s completely nude, unarmed fight against multiple assailants in a bath house is a harrowing example of masculine vulnerability onscreen; in Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant (1992), Harvey Keitel is laid totally bare before us with nowhere to hide, revealing a sad, primordial being clinging to the margins of society; in Peter Greenaway’s grotesque, formalist satire of bourgeois overconsumption, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover (1989), gluttony its taken to its most logical extreme, including a place of honor for the cock, reduced to a punchline; in Zola (2020), a montage of dicks captures a dispassionate, monotonous night of sex work; in Boogie Nights (1997), a man’s life is reduced to the size of his manhood, and, in the ultimate sight gag, it’s a prosthetic.

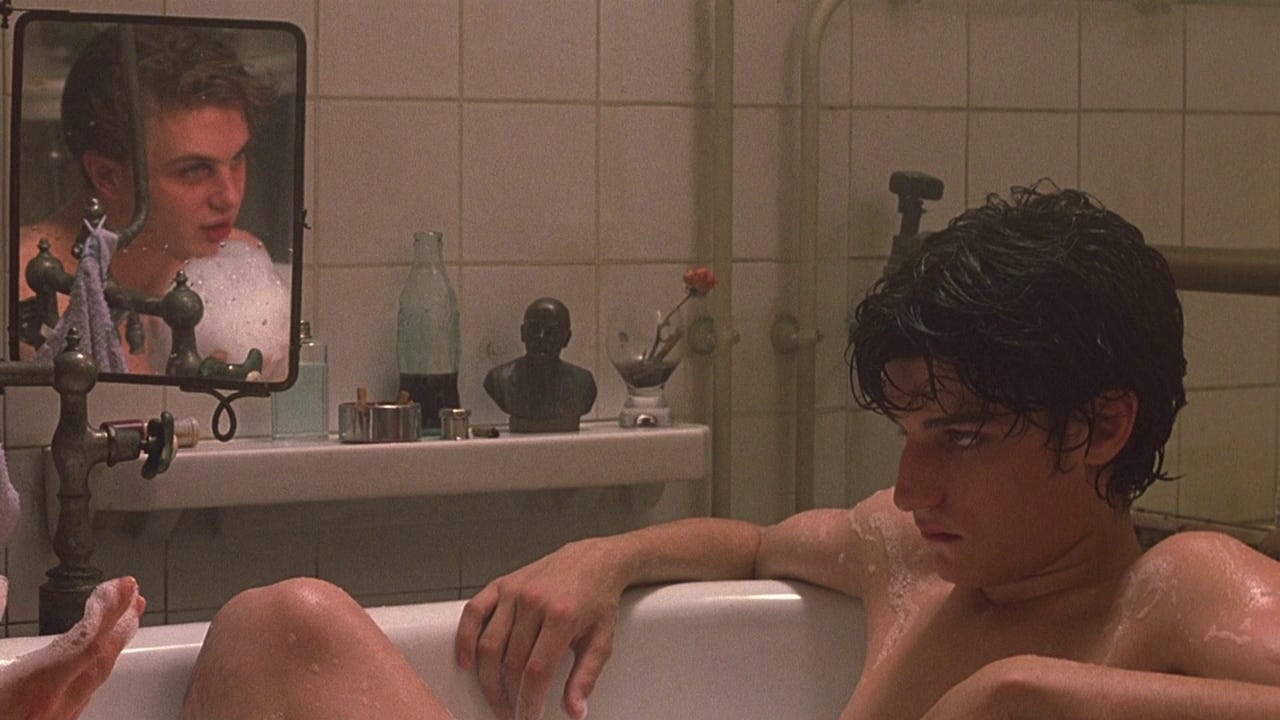

This program—named for male-stripper classic The Full Monty (1997), which, ironically, does not go “full monty,” aka baring it top to tip—looks back at the history of the male-presenting full-frontal in film, and the accompanying struggles with censorship such movies have faced.5 Before the days of streaming, producers would ensure the cuts of films adhered to the suggestions of the MPA, or risk a limited distribution outside of home video sales, diminishing their commercial viability. As previously mentioned, this has had a significant impact on the depiction of nudity and sex in film, encouraging filmmakers to skew conservative.6 Although the MPA claims not to distinguish between male and female nudity, there does seem to be an unspoken cultural bias against films that do show significant male nudity, particularly when accompanied with scenes of considerable sexual heft (cocks played for laughs, such as in Borat or Forgetting Sarah Marshall, both included here, do not seem to face this same level of scrutiny), as if the very presence of a penis makes a film pornographic. In terms of programming, I can only say that, anecdotally, trying to source older films that cross this threshold on streaming platforms proved tricky: sure, lauded films like Trainspotting (1996) and The Piano (1993) are fairly easy to find, and films like Wild Things (1998),7 Shame (2011), Gone Girl (2014), and Saltburn (2023) remain cultural punchlines, but films that present this anatomy in certain sexual situations—such as queer sex, unsimulated sex, non-normative sex, or sex within films from certain markets, such as Chinese-language cinema (which is subject to state censorship), can be incredibly difficult to track down outside of physical media (a sobering reminder of its necessity), if that is even possible (like Summer Place, the first Mainland Chinese movie to feature full-frontal male and female nudity, which, banned in China, has since completely fallen through the cracks). Incredibly significant, high-profile works with full-frontal male nudity and transgressive visions of sex like Flesh (1968), Pink Flamingos (1972), Equus (1977), Taxi Zum Klo (1980), Pola X (1999), Intimacy (2001), Y tu mamá también (2001), Young Adam (2003), and The Dreamers (2003) are completely unavailable to stream (legally), be it for “rights issues” or simply the extremity of the content. Such limitations have not and will not ever affect the content of our programming, however, and I’ve sourced ways to watch these films online as best I can on The Spread.

Of course, the absence of nudity in popular culture doesn’t discourage cultural preoccupation with naked bodies, it just reinforces messaging that bodies are inherently something to conceal, as if states of nudity aren’t a foundational aspect of human existence, and therefore something worthy of study in art. My friends like a story I tell about hearing Shaggy’s “It Wasn’t Me” on the radio at age 8, and, confronted with the images of graphic sex conjured up by the song’s evocative lyrics, fell into what only can be described as a sexual panic, my first, as I failed each night to expunge Shaggy’s words from my mind, envisioning limbs and genitals and mouths entwined in ways I’d never imagined before, confident I’d solidified my place in hell for such thoughts. Each discovery of self arrived by such accidents, all from exposure to art, including my first scene of full-frontal male nudity, courtesy of—of all things—Graham Chapman in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), included here, in a scene I returned to and fled from in equal, angst-inducing turns. Fear is a powerful force: it justifies our discomfort at things we’ve relegated to the shadows, ignorance exchanged for a vague feeling of safety. The relegation of forms of nudity to pornography—itself its own medium, expunged from mainstream art—envisions an existence in which any kind of state of undress, sexual or otherwise, can only be studied within the fairly rigid parameters of sexual congress: “Obscenity8 only comes in when the mind despises and fears the body, and the body hates and resists the mind,” D.H. Lawrence wrote in Lady Chatterley's Lover, a novel with two adaptations in this program (including one by a man named “Just Jaeckin”).

In a 2004 interview with TV Guide, tellingly titled “Whoa! Shattered Star Goes Full Frontal,” then-rising actor Peter Sarsgaard discusses his full-frontal scene in the film Kinsey (2004), in which the titular sexologist (Liam Neeson), upon seeing his assistant naked for the first time, undergoes a moment of sexual awakening that complicates his own understanding of human sexuality, further informing his research, as he’s forced to finally hold the mirror up to himself. Speaking of the scene, the actor notes, “The reason I'm nude is to test the waters before I [kiss Dr. Kinsey] later in the scene. It had a purpose. It’s not nudity for you guys, it’s nudity for him.”

Crushed Velvet: the Many Men of James Mason

In discussions of the all-time great icons of classic film, James Mason—a screen titan who played a beguiling mix of hero, anti-hero, and villainous personas—tends to get sidelined, if not excluded all together: in Turner Classic Movies’ 2006 film guide, Leading Men: The 50 Most Unforgettable Actors of the Studio Era—a text that guided my own Hollywood education—the late Robert Osborne, in recounting all of the famous leading men he was forced to exclude from the volume, doesn’t even mention James Mason (in a list that includes fairly forgotten figures like Lew Ayres, Dana Andrews, Stewart Granger, and John Payne… none of whom can lay claim to the impressive filmography amassed by Mason). Whither James Mason? Could it be that the actor’s performances were so nuanced and varied, his creative output so singular for his era, that he’d slipped through the cracks altogether? A handsome, erudite actor—the cinematic personification of “the doomed Byronic male,” per author Sarah Thomas—Mason, having graduated from the stage to the screen, became Britain’s top box office star in the 1940s, appearing in a number of films for Gainsborough Pictures—a studio best remembered for lurid melodramas that incorporated themes of avarice, lust, familial betrayal, and psychosexual frustration at a time of comparatively conservative censorship standards stateside. With his distinctly cultured, deep voice, often described by admirers as “velvety,” Mason gleefully played sadistic but alluring bastards in British classics like The Man in Grey (1943), The Seventh Veil (1945) and The Wicked Lady (1945), which proved so popular that he made the move to Hollywood—where he found success, eventually, after a considerable learning curve.

Mason’s cinematic output, even from this period, is considerable, including a run of fantastic underrated film noirs, like Carol Reed’s classic IRA thriller Odd Man Out (1947) and (recently re-discovered) gems like The Reckless Moment (1949) and Caught (1949). In MGM’s buzzy adaptation of Madame Bovary (1949), he plays Gustave Flaubert, on trial for obscenity, in an odd framing device added to mitigate concerns surrounding the book’s depiction of sexual malcontent. In beloved Technicolor fantasy Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), he is a doomed seaman, cursed by loving a too-beautiful woman (Ava Gardner). These films trade on the actor’s compelling promise of danger, while reveling in his sexual charisma and calming gravitas that usually sent him to his doom by film’s end.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the talented actor became an established international star, thanks to a pair of seismic films: George Cukor’s musical remake of A Star is Born (1954), in which he memorably plays the washed-up, alcoholic husband to rising star Judy Garland (a reverse of the real-life career dynamics at play), threatening to steal the film out from under her, and Richard Fleischer’s groundbreaking adaptation of Jules Verne’s classic novel for Walt Disney, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), in which he embodies the definitive version of the destructive Captain Nemo in one of the studio’s first (and most ambitious) live-action hits. In this untouchable era, Mason delivered on that dual, almost contradictory screen persona that made him such a terrific leading man for the morally ambiguous works he cut his teeth on in classic British cinema: handsome, obviously; charming, invariably; seductive, always, and to one’s own peril… you’re never really sure whether you can trust him not, even when the film assures you it’s safe to do so. He quite literally played the poster boy for betrayal, Brutus, in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s lauded 1953 adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, as well as the ultimate gentleman villain in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959); you almost can’t help but root for him, if only because he’s just so deliciously wicked (“That wasn't very sporting, using real bullets”) .

If Mason’s accent revealed his posh past career at the Old Vic reciting the classics across the British footlights, his screen work was remarkably modern, a compelling bridge between the divergent acting styles of pre-War/post-War eras, making him feel like a complete anomaly, and a difficult star to pin down. In the early 1960s, he made a career move seemingly antithetical to his own self-preservation in the industry, accepting a role considered radioactive by any of the aging leading men of the day: that of middle-aged predator Humbert Humbert in Stanley Kubrick’s controversial adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Great American Novel, Lolita. The first film in which Kubrick retained full artistic control—and the start of his remarkable career as the great auteur of late 20th century cinema—Lolita (1962), famously told in deceptive first-person perspective by Humbert, who grooms and kidnaps a 12-year old girl from her mother’s boarding house, encountered considerable censorship issues in the process of adaptation (“How did they ever make a film out of Lolita?” the film’s infamous poster and trailer asked, and well, basically… they didn’t). Adapted for the screen by Nabokov himself, the film’s odd tonal shift from tragedy to sex farce accompanies a necessitated change in Lolita’s age from 12 to the more-socially-acceptable grooming age of 16, alongside the alleged mandate that the young actress cast had to appear on the bustier side (Sue Lyon, 14 at the time, memorably took on the role). Kubrick’s film has plenty of problems (breakout star Peter Sellers’ flashier performance, in my opinion, has aged somewhat poorly), but James Mason isn’t one of them: playing off that signature ruinous charm, he’s pitch-perfect as a man so adept at manipulating people that he gets away with continued violations despite the obvious visibility of his crimes. Sixty years (and one incredibly fraught Adrian Lyne adaptation) later, you still can’t really imagine anyone else in the role.

Even as he became largely typecast in a revolving door of Nazi and Soviet spy roles in genre films of varying quality in the 1970s, he never dropped that eerie command of the screen, memorably appearing in certified cult classics like Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron (1977), which inspired Inglourious Basterds (2009); The Boys from Brazil (1978); the incredibly upsetting (and demythologizing) Mandingo (1975), which, for better or worse, inspired Django Unchained (2012); and Tobe Hooper’s classic Stephen King adaptation Salem's Lot (1979)… never under-developing his carefully-cultivated screen characters. Sidney Lumet, signature “actor’s director,” who worked with Mason four separate times, said of the man, “I always thought he was one of the best actors who ever lived. Whatever you gave him to do he would take it, assimilate it and then make it his own. The technique was rock solid, and I fell in love with him as an actor… he wanted good billing and the best money he could get, but then all he ever thought about was how to play the part.”

The late Christopher Plummer, who played Sherlock Holmes to Mason’s Watson in Bob Clark’s Murder by Decree (1979), put it slightly more eloquently—according to TCM—stating upon the actor’s death in 1984, “What a horrendous loss to motion pictures, what an artist of the celluloid, capable of such profundity and grace.”

That’s it for September! See you next month for our Spooky Season programming, an annual tradition four years in the making, and until then, what possessed you to come blundering in here like this? Could it be an overpowering interest in art?

A film so influential, it’s still being referenced to this day, such as in the buzzy music video for Gen-Z pop singer Addison Rae’s “Diet Pepsi.”

The controversy (eventually) brought Lamarr to the attention of Hollywood: Louis B. Mayer signed her to MGM in 1938 after changing her name to better distance herself from the film. Allegedly, her then-husband, literal arms merchant Friedrich Mandl, who had ties to Mussolini (and later, Hitler), tried to buy up all the prints to ensure it was never seen. For Lamarr herself, it apparently generated a complex feeling of regret, as she claimed that she had been tricked into believing that the nudity would not be so explicit.

In Rolling Stone’s obituary for the legendary producer, they note, “[His brother-turned-business-partner] Gene said that they lived by the notion of: Who needs stars when you’ve got a great, salacious poster?!”

Consider the (well-earned) backlash to Seth MacFarlane’s cringeworthy song “We Saw Your Boobs,” at the 85th Academy Awards in 2013, a number that grossly catalogued famous female celebrities who had shown their breasts on film, including in scenes of sexual assault. Despite the outcry, MacFarlane claims he was asked back the next year.

In recent years, male full-frontal nudity has become something of a hot topic in media, mostly on streaming services and premium television: fairly recent seasons of White Lotus, House of the Dragon and Euphoria, all for HBO, have notably incorporated full-frontal scenes of male nudity, yet retain their reputations as water-cooler programs. Premium cable television is not beholden to the review and approval of the Motion Picture Association, aka the MPA (formerly the MPAA, the Motion Picture Association of America), which assigns film admittance guidelines prior to theatrical distribution.

This can be almost hilariously petty and granular. In the case of Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (1987), the MPAA demanded the removal of a shot of Mickey Rourke's “buttocks thrusting” in a sex scene to avoid an X rating; after two unsuccessful appeals, the director cut just 10 seconds from the film to achieve an R rating.

Bacon parodied his own infamous full-frontal scenes in Wild Things (1998) and Hollow Man (2000) in 2014 with the tongue-in-cheek #FreeTheBacon movement, calling for larger gender parity in onscreen nudity.

Obscenity is defined by the United States government through the “Miller Test,” a three-pronged determination established in Miller v. California (1973) used to assess (and censor) artistic expression: whether the “average person” would find the material filthy; whether the material depicts sex in a “patently offensive” way; and whether the material lacks “merit” in adherence to a larger calling, be it artistic, scientific, or political.