April Streaming

This Month: 50 Jaw-Dropping Film Stunts, Movies Head to the Mall, and the Careers of Two Legitimate Screen Icons (Plus: Cowboy Carter)

Welcome to April streaming.

Lately, I’ve been watching a lot of On Cinema at the Cinema, Tim Heidecker’s online movie review show, hosted with Gregg Turkington, in which the comedian struggles to recap the latest film releases against a backdrop of escalating offscreen personal problems, litigated on the program, as well as his own limited knowledge of movies. It feels like there should be a sort of kayfabe protecting the self-contained lore of the show, so I’m not going to say it’s a bit, I’ll just say that binge watching the show now after (almost) four years of The Spread is a bit like Salieri hearing Mozart for the first time and realizing, with awful clarity, that he will never be as good at the thing he loves doing most in this world: in my case, being a loser about movies. Frankly, I’ve been pegged: a self-important film buff, spouting unchecked facts on their own labor of love, which is both deeply embarrassing and honestly a bit liberating. “This is as good as a movie can get and it’s so great that they’re still making these kinds of movies!” Heidecker exclaims in a recurring soundbite on the show, which is something I’ve undoubtedly said in this very newsletter. It’s humbling, but movies must be programmed, so here we are once again.

This month, we’re looking at some of the coolest stunts in film history, from the silent era to our current moment, and breaking down just how they managed them. Then: get in loser, we’re going shopping… on the screen! It’s Movies at the Mall, and there are two films that can be found in both programs. Can you guess what they are? If you said Police Story (1985) and Terminator 2 (1991), you get an Auntie Anne’s pretzel on me; it’s up on the second level, next to OshKosh B'gosh. Finally, for our actor’s showcase, we’re featuring two of the greatest screen icons of the Classic Hollywood era, paragons of wit and class who appeared in four films together, making them (in my estimation) one of the most underrated screen couples of the studio era. Also: a little Western encore (and some thoughts on Cowboy Carter).

When you’ve got movies like Tom Cruise in them, you can’t lose!

The Stunt Hall of Fame

“I’m not a cowboy…I’m a stuntman. But that’s a very easy mistake to make,” Kurt Russell, as Stuntman Mike, vehicular serial killer, informs his future prey, in Death Proof (2007), Quentin Tarantino’s ode to 70s genre pictures and the techniques used to capture some of the craziest, deadliest acts ever seen on film.

There’s really no better way to describe the group of men and women who have historically thrown their bodies into performing some of the most daring feats of strength and bravery onscreen: they really are cowboys, operating in No Man’s Land with a code of honor and set of tools all their own, like vehicle safety boxes, crash pads, decelerators, wires…and in some extremely dangerous instances, absolutely nothing at all.

At last month’s Academy Awards, a segment “honoring” the men and women of the stunt community, without whom our lust for onscreen violence and thrills would never be satiated, concluded without fanfare. Those hoping to see the introduction of a long-overdue Academy Award honoring outstanding stunt work—so they could be, you know, actually honored—were disappointed once again: just the latest reminder of how undervalued and under-appreciated stunt coordination remains in Hollywood, despite the community’s contributions to the development of film language. It’s an artistry all its own, involving a myriad of moving parts as wide-ranging as physical coordination and actual engineering work (planning the stunt, executing the stunt, and figuring out how the hell to shoot the stunt). But it’s not all bad news: just this week, SAG-AFTRA and DGA approved the first-ever credit of “stunt designer” to account for the wide range of work done by film stunt coordinators; Chris O’Hara will be the first “stunt coordinator” to receive this credit on next month’s release The Fall Guy (2024), which stars Ryan Gosling (as a stuntman) and looks incredibly fun. Congratulations to him!

This long-gestating program looks back at 50 groundbreaking stunts in film history, from the death-defying work of the early silent comics like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton to the groundbreaking work of professionals like Yakima Cannutt (Stagecoach, They Died with Their Boots On, Ben Hur) and Dar Robinson (Papillon, Highpoint, Sharky’s Machine) , as well as the auteurist efforts of performers like Gene Kelly, Jackie Chan, and Tom Cruise, who routinely threw caution to the wind in the search to capture the sublime on film, freezing it in perpetuity.

This program has every kind of stunt imaginable: car chases, car flips, car jumps, fight coordination, big jumps, bigger jumps, skydives, horse riding, aerial stunts, cliff jumps, motorcycle tricks, highwire acts, and plunges into raging rapids. And, yes, just about every dumb-ass centerpiece stunt Tom Cruise has done in the Mission Impossible movies. He was inspired by Jackie, Jackie was inspired by Gene Kelly, Gene was inspired by Buster Keaton… all of these feats of grace and strength are in conversation with one another, pushing the possibilities of film to new and (deeply thrilling) places. It bears repeating: these performers not only designed the stunts, they had to establish techniques to film them all as well, further developing the language of cinema. So why isn’t there a “Best Stunt Coordination” Academy Award? Where is the canonical celebration of stunt work? Where are the proper retrospectives? Why do we talk about stunt work in terms of marketing, and rarely in terms of artistry? Can we get some kind of definitive text on the field? How many stunt people have almost died in the pursuit of art, without proper recognition of their achievements?

Of course, some stunt men do die, and dangerous stunts involving non-stuntman can result in death. We covered several instances in which performers died on set in our prior Movies with Real Crimes program, including the tragic behind-the-scenes stories of films like Noah’s Ark (1928), Shark! (1969), The Twilight Zone Movie (1983), The Crow (1994), and Vampire in Brooklyn (1995). Dar Robinson, who once threw himself off a building backwards, falling 200 feet for the Burt Reynolds’ Stick (1985), died just one year later in an onset motorcycle accident while making Million Dollar Mystery (1986). It’s a tough, thankless life, but someone’s got to do it, because it looks so, so much better than computer generated stunt work.

As CGI overtakes practical effects work in contemporary filmmaking (rendering everything boring in the soulless, grey muck of the dreaded soundstage), I think it’s incredibly important to look back at our cinematic forbears and appreciate the lengths they went through to develop the language of action cinema. The best action films of our current moment use computer-generated effects only in tandem with well-coordinated practical effects (like Mad Max: Fury Road, RRR, the Mission Impossibles, and the films of Monsieur Nolan, to name a few). That’s because practical effects hold up in ways that computer graphics cannot and will not: films like Raiders of the Lost Ark look better than movies that came out last year, because the stunts were done so seamlessly in conjunction with the rest of the filmmaking, by professionals. There’s a tangible, grounded quality to filmmaking in a physical space that no amount of post production can account for, just as there’s a real thrill in seeing the biggest movie star in the world routinely almost die in feats of strength in the pursuit of entertaining us. Thank a stuntman in your life today!

Making Mr. Right: How Archie Leach Became Cary Grant

You’ve likely seen the tongue-in-cheek quote that aptly summarizes the specific appeal of screen god Cary Grant, born Archibald Leach in Bristol (in working class circumstances right out of a Charles Dickens novel): “Everyone wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant.” The suave, ridiculously charming leading man may be the platonic ideal of a male movie star, but “Cary Grant” was a fantastical creation, meant to papier-mâché over a hungry, dedicated hustler who pulled his way up out of his Dickensian childhood (his depressive mother was institutionalized by his alcoholic father, who told his son that she died; Grant, who was nine at the time, didn’t learn that she was alive until he was 31) to become one of the greatest onscreen performers of the 20th century and a definitive icon of American film. His mid-Atlantic accent, so crucial to our understanding of early 20th century notions of class, hid a course, cockney drawl; his seemingly permanent bachelordom in the public eye hid his queer sexuality, which likely skewed somewhere between bi and gay. He was a creation: total smoke and mirrors, but it made him uniquely qualified to sell the product. Arriving in America at just 16 as part of a theatrical touring group, he made a name for himself on vaudeville, where he cultivated the slapstick comedy skills (and exaggerated mugging) he’d later bring to (eventually) beloved films like Bringing Up Baby, Arsenic and Old Lace, and His Girl Friday. When he made the transition from theater to Hollywood, like so many others, he came up playing a pretty, dashing twink to older vamps like Marlene Dietrich and Mae West in films like Blonde Venus, She Done Him Wrong, and I’m No Angel. But Grant really struggled to find a niche in Hollywood and worked for several years without making much of a splash. He didn’t take off as a comedy star until 1937’s Topper, where he plays a ghost, which begat the seismic run of films we’d later come to appreciate better, most of which are now regarded as some of the greatest American films of all time: The Awful Truth (1937), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Holiday (1938), Gunga Din (1939), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), My Favorite Wife (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940). What a run! These films are a beguiling mix of action, drama, and comedy: in Bringing Up Baby, he wears a woman’s bathrobe and chases after a rogue leopard; in Only Angels Have Wings, he’s a paragon of tough, Hawksian masculinity, and cries onscreen; in The Philadelphia Story, he’s sex and wit personified, the absolute embodiment of the eccentricities and whims of the upper class. But nothing trumps his performance as an unscrupulous editor in Howard Hawks’ fast-paced newspaper comedy opus, His Girl Friday, where he tears through lines of dialogue like tissue paper and makes a number of terrifically funny noises and gestures. I’d say it’s one of the greatest comedic performances ever committed to film, if Grant didn’t surpass his own work with Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), my personal favorite Cary Grant performance (I like ‘em zany). These early triumphs were just the first act of a screen career that would continue into the post-War period, even as he grew older and grayer before our eyes (made more obvious in color films). The Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, clearly found in Grant something no one else was quite able to pull out of him: menace. Hitch weaponized Grant’s considerable charm in his Hollywood-era classics Suspicion (1941), where he maybe wants to kill his wife, and Notorious (1946), in which his bitter cynicism at falling for his honeypot asset tinges their romance with sadomasochistic undertones. Later, Hitch would make him a professional victim of circumstance and female desire in To Catch a Thief (1955) and North by Northwest (1959), the latter of which granted us the most indelible image of the star’s career: Grant, in full suit, running from a plane in a crop field. Who else could retain elegance and grace in such circumstances? Despite his popularity with audiences, he never really earned the professional recognition he deserved in his lifetime: he was nominated for just two Oscars (for tear-jerkers Penny Serenade and None but the Lonely Heart), famously never winning a competitive Oscar. Nevertheless, he was named the second greatest screen legend of American film history (behind Humphrey Bogart) by the American Film Institute and remains one of the most beloved actors of all time—and, I think, an entry point into classic film for a lot of young cinephiles. His screen triumphs are a reminder that acting doesn’t need to be “modern” to be accessible: at the end of the day, we all want to watch someone as cool and handsome as Grant pratfall, mug, yelp, and—even!—cry. Cary Grant may have been the model of 20th century masculinity, but at the end of the day, he was just a man, as real as any of us, and all the more intriguing for it. He’s the real-life Don Draper, wearing masculinity like a well-tailored suit. “I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be until finally I became that person,” Grant once said. “Or he became me.”

My She Was Yar: The Movies of Katharine Hepburn

“I think—and I’m not saying I know—I think that I’ve always thought of myself as an actor,” Katharine Hepburn confesses in her autobiography Me: Stories of My Life, released in 1991. The legendary actress of stage and screen was then in the twilight years of her life, capping off a celebrated career that included a record-setting (and still unmatched) four Academy Award wins for Best Actress (out of 12 nominations, a record that has only been surpassed by Meryl Streep), in addition to numerous other accolades from pretty much every cinematic establishment. In 2000, just nine years later (and three years before her death), she was named the greatest female star of Classic Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute. In her heyday she was a complete outlier: a well-educated, sophisticated, (at least) bisexual, and opinionated woman who wore slacks and openly challenged men onscreen, including her longtime partner, Spencer Tracy, with whom she appeared in nine movies, beginning with their far-too-sexy chemistry on Woman of the Year (1942) and including stone-cold classics Adam’s Rib (1949), Desk Set (1957), and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (there are some…others…we don’t acknowledge, like Dragon Seed (1944), the one where Kate dons yellowface). In these movies, Tracy and Hepburn are complete opposites, negotiating ideas of gender, sex, and professional ambition as fighting equals in a decidedly unequal world, even articulating proto-feminist ideas in the process (paraphrasing some unknown adage, she gave him class and he gave her sex). Politically-minded, Kate publicly devoted herself to liberal causes her entire life, fighting for civil rights and gender equality and casually breaking new ground alongside Tracy in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), one of the first films to depict interracial marriage (at the time of filming, "miscegenation" was still illegal in 17 states, which would be struck down by the Loving v. Virginia ruling just six months before the film was released). By all accounts, she was a headstrong, difficult woman, but that just made her all the more capable of advocating for herself and her proclivities, casually groundbreaking as they were. She was married (and divorced) just once, had no kids and never remarried: in the back-half of her career, she’d routinely play aging spinsters (or fraught matriarchs), bringing class (and grace) to supposedly pathetic and/or despicable characters, dangerous in their subversions. In my personal favorite performance of hers, in David Lean’s Summertime (1955), she sheds her pride—but none of her fire—for a chance at long-denied romance while on vacation in Venice; it’s a formative performance of crushing loneliness pulled from the tough-fronting, sometimes Campy actress, whose larger-than-life persona can sometimes eclipse the tremendous range she possessed as an actress. Women can be tough yet fragile, intelligent yet foolish, and strong yet vulnerable. “The time to make up your mind about people is never,” she says, righteously, in The Philadelphia Story, the role that secured her legacy after being labeled “Box Office Poison” in the late 1930s, following a series of flops (some of which would later be reassessed as outright classics, like Bringing Up Baby and Holiday (both with Cary Grant, with whom she had a sexy, underrated onscreen chemistry) and Stage Door (1937), where she crosses verbal swords with Ginger Rogers, Lucille Ball, and Eve Arden. The Philadelphia Story (1940), for all its retrograde elements, changed my life, a little bit, with the notion that imperfection is an important part of the human experience, as is the ability to extend grace to those who have fucked up. For a woman, that can be a tough, bitter pill to accept at times, and I frequently think of the screen idol, drunk off her ass, being carried to bed by Jimmy Stewart, when I stress over my own mistakes and flaws. Who else could have played the humbled goddess so perfectly?

John Howard: But a man expects his wife to...

Katharine Hepburn: Behave herself. Naturally.

Cary Grant: To behave herself naturally.

I had to find sanctuary in a place where I could gather my thoughts and regain my strength: Movies at The Mall

Of all the streaming programs I’ve poured my heart, soul, and time into, surely this is the one I’m most qualified to cover: scenes at the mall! No, not the much-maligned Paul Mazursky film Scenes from a Mall (1991)—set at the Beverly Center—but all films that take place partially or entirely at a mall. For those who don’t know, I love the “mall,” that once-beloved post-War invention that replaced walkable town centers with marbled, air-conditioned, hermetically-sealed spaces to accommodate all your purchasing needs in one place. As a former denizen of Dallas who didn’t get a driver’s license until I was 17, the mall was my home-away-from-home, in the sense that it was the only place I could regularly get dropped off to meet my friends without parental supervision. I suspect for a lot of kids in suburban or rural areas, the mall played a similar role in their lives. There were three malls of significance to me: the massive Galleria Dallas, where I spent halcyon days hugging the railings of its central ice rink; NorthPark Center, a landmark luxury mall where I first saw Lady Gaga perform in a busted bodysuit at a Miss Sixty fashion show; and the (since demolished) Valley View Center, the “edgier” mall that had the first Forever 21 in town and was therefore the most significant to me in my teens. Yes, Dallas loves a shopping mall (or a strip mall) and, like all malls, Dallas malls shared basic traits: food courts with recognizable chain names; a giant central fountain and endless seas of planters (for elegant ambience); maybe a movie theater, if you’re lucky; and an assortment of random events year round meant to pull in families and young consumers to its hallowed grounds. “The Mall” was a cultural phenomenon and byproduct of a gentrifying nation, pushed to suburban enclaves after World War II and desperate for a facsimile of community. Malls invented a universal, almost gross mimesis of a bustling town square, sanitized and safe, that people typically had to drive or bus to, rather than engage with as part of their everyday commute. This is captured, quite succinctly, in Back to the Future (1985), in which Michael J. Fox journeys backwards in time from the local mall parking lot to the 1950s, which still has a robust town center, including a diner and movie theater. The trend towards Malls follows the larger erasure of public non-commercial space for folks — particularly young people— to congregate at the end of the 20th century… which is troubling… because The Mall is now dying.

The mall may have had it all… but nothing gold can stay. In recent years, with the decline of brick-and-mortar shops in favor of online retail, malls across the country have shuttered—or, even stranger, become purgatory-like spaces (called “dead malls”) with just a handful of functioning shops, if any. These spaces look like something out of Dawn of the Dead: half-demolished, half-cleared out structures still stand, like abandoned temples to some long forsaken God. Inhabitants are now generally random stragglers or senior citizens, walking through them for exercise. As malls set up curfews and restrictions for teenagers (which I think is just rotten!), it’s hard not to turn a bit wistful at something we’re truly losing: a physical place for young people (or, frankly, the elderly) to hang out that’s relatively safe and structured.

In terms of cinema history, the first Mall Film of Note has to be the aforementioned Dawn of the Dead (1978), in which the maestro of cult horror used the site of luxury commerce as a stage for zombie invasion shenanigans, a critique of late stage capitalism and the open-throated worship of the all-mighty dollar, which would only become more relevant in the coming years. The Reagan years were fruitful fodder for Mall Cinema: throughout the 1980s, film turned to the mall to mine it for content, beginning with the Sherman Oaks Galleria (still with us), a popular filming location following its use in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), then Valley Girl (1983), Night of the Comet (1984), Commando (1985), Chopping Mall (1988), and Phantom of the Mall: Eric's Revenge (1989). Easily our most important mall in terms of film history! But the Sherman Oaks Galleria is just one of the shopping malls featured in this program, which doubles as a casual anthropological study of the shopping centers that served as a setting for so many memorable (and… less memorable) movie moments. The Mall is perfect for movies because it can bring so many disparate characters to one location, much like the wide-ranging stores in the mall itself… and the films included here!

BONUS! Encore: The Western Film, a Primer

We’re at apex cowboy currently, what with the release of Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter, Waxahatchee’s Tiger Blood, and poor little Kacey Musgraves’ Deeper Well… not to mention the sweet surprise of Orville Peck’s lovely duet with Willie Nelson, “Cowboys Are Frequently Secretly Fond Of Each Other,” a cover of a 1981 queer country song first recorded by Willie in 2006 as a show of solidarity to his tour manager. We’re bringing real country back, folks, and with it, a return to the well of last month’s programming: the Western Film, updated with current streaming information. Imagine my delight at learning that Beyoncé drew inspiration from a number of Western films while making Cowboy Carter, several of which were included in last month’s programming, including Urban Cowboy (1980), The Hateful Eight (2015), The Harder They Fall (2021), and Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)… talk about accidental synergy! And for those of you who aren’t a fan of the uneven, bloated first-half of Cowboy Carter, which can distract from the through line of Beyoncé’s sonic experimentation, I (respectfully) re-cut it, based on hours of listening; all of my expertise, whatever it may be, as a Beyoncé fan since age 8; and my earnest love of country music, which has been neutered, whitewashed, and misrepresented by the Nashville machine for decades.

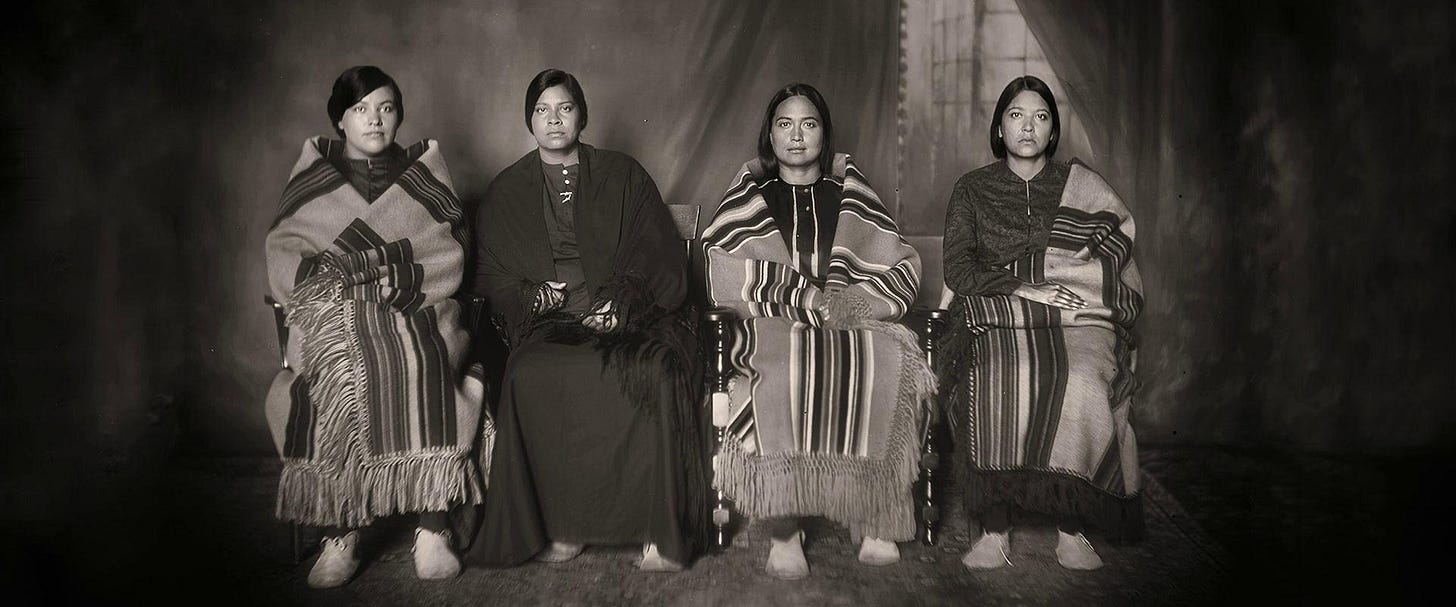

Much has been made about how Beyoncé aims with this album to reclaim the history of American country music, which derives from rhythm and blues and gospel music and owes an unacknowledged debt to the countless black musicians who played a part in developing its sound (never forget that Country Music God-King Hank Williams learned how to play guitar and perform from a black street musician named Rufus “Tee-tot” Payne, who taught him the blues). To aid Beyoncé in her mission, she brings on the (massively underrated) Linda Martell, the first black woman to sing at the Grand Ole Opry (who, like many other pioneering black female artists from the south, has never gotten due respect in the world of country music despite laying down genre-defying country tracks, much like Big Mama Thornton, Barbara Lynn, Merry Clayton, Millie Jackson, Candi Staton, and many more). But something I think that has been under-discussed, apart from Beyoncé’s cinematic references, is the way Beyoncé interweaves regional sonic influences into the album to make the sound of it feel so deeply personal to her. When Beyoncé and The Chicks performed a mash-up of “Daddy Lessons” and “Long Time Gone” at the 2016 CMAs, which led to the creation of Cowboy Carter, people (offscreen) were gagged (and racist-ass Nashville was Pissed, refusing to post the performance online), but I don’t think anyone properly contextualized the larger cultural significance of the moment: that’s Texas history, baby! That’s that Outlaw Country sound we all crave to return to (and Beyoncé luxuriates in on Cowboy Carter). “That’s my song!” Beyoncé laughs, mid-performance of “Daddy Lessons,” right as the (historically progressive) Chicks launch into a very pointed bit of “Long Time Gone,” their scathing critique of the country music industry from 2002: “They sound tired but they don’t sound [Merle] Haggard / they’ve got money but they don’t have [Johnny] Cash.” If Beyoncé is reclaiming something on Cowboy Carter, its not just country music history: its ownership of the regional sounds that shaped her love of music and have been bastardized by generations of ersatz cowboys: city slickers and poseurs with no attachment to (or appreciation of) the region these sounds come from and the long, rich history behind it all. She may be the biggest pop star in the world, with an oftentimes frustrating personal profile that keeps us at arm’s length, but her true artistry (and I’m being completely earnest here) comes across in how she weaves (seemingly) disparate elements through the prism of her own cultural heritage and identity (“My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana/ You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas ‘bama” she famously sang on “Formation,” also in 2016, as a reminder of who exactly she is and where she comes from, following years of critiques of her blackness). Texas music has a rich, unique heritage all its own with its own, and it’s not remotely culturally homogenous: from norteño music; swamp pop out the Bayou; the “West Side sound,” (aka Chicano soul) out of San Antonio, “chopped and screwed” hip-hop out of Houston, and Western swing… these sounds all came together through conversation between different communities and cultural traditions. You’ll find these influences all over Cowboy Carter, sometimes, in a single song: in “Ya Ya,” Beyoncé, introducing herself from “a rodeo chitlin circuit,” travels through a number of pop genres, referencing everything from the her beloved Tina Turner (inarguably her number one influence) to 60s girl groups, to funk, to swamp pop, to trap… I think it’s really weird… and neat! I… may go long on it for the newsletter. Watch this space. And in the meantime, watch these movies.

That’s all for April, folks! We’ll be back in May with fresh programming. Until then, if you want some basic bitch, go to the Beverly Center and find her!