As I stare down another streaming program amidst the dull, aimless void of the first week of January, I wanted to take a moment to look back on some of the wonderful films that I watched for the first time in December. It was a heady month full of terrific first releases (2023: what a year for film!), and I tried my best to whittle down the list as far as possible.

My poor editor is currently confined to bed, capable of very little forms of expression beyond moans and pitiful wails. Has anyone ever suffered like a 32-year old man with a cold? Here’s hoping you and yours are currently free from such burdens, but if not: I do have some movies you can watch in your infirmity! Just go a little easy on the copy while he recuperates.

Keep an eye out for January streaming, dropping (hopefully) next week, which will include a round-up of all my favorite first watches of 2023.

The Iron Claw (2023)

Director: Sean Durkin

“THIS IS VON ERICH COUNTRY” the marquee of the Texas Theatre in Dallas proudly proclaimed on opening night of The Iron Claw, Sean Durkin’s terrific dramatization of the talent (and tragedy) of the iconic Denton-based Von Erich wrestling clan. In the row in front of us, a wrestling fan brought his two young children (do not do this), who climbed around the seats; in the bathroom, older locals recounted their memories of seeing the elder Von Erich wrestle back in the day; people (me) weeped openly during the end credits. It was a heightened environment for the surprisingly understated (and heartbreaking) film, and it really left an impression on me. This is Von Erich country, all right, and anyone that’s been raised within (or adjacent to) Texas athletics knows exactly what that means: men were expected to be tough, without comment. There’s actually a key professional wrestling term that lends itself directly to this: kayfabe. Writing about the Von Erichs in 2005, John Spong for Texas Monthly describes kayfabe as a carnie code of silence and solidarity made manifest as “wrestling’s curtain” that carried over to — and governed the world of — professional wrestling: “Everybody who knew the Von Erichs says they all were good boys,” Spong notes. “But there’s always an addendum: They did have their demons. And when it came time to address them, the Von Erichs concentrated on what the world saw outside the curtain.” Durkin’s film follows those demons (and the almost Biblical tragedy that followed), which were likely exacerbated by a number of factors related to wrestling, including the toxic, hypermasculine culture cultivated by their extremely disciplined father, who poured all of his deferred hopes and dreams for his own career into each of his sons (the film takes some historical liberties, the most controversial of which was the exclusion of one of the Von Erich sons, Chris Von Erich).

In the film (and in real life), the titular “iron claw” is a signature move created and perfected by professional wrestler Fritz Von Erich (character actor Holt McCallany), which he teaches to his four sons, three of whom become popular wrestlers at their father’s (extremely influential) promotion, World Class Championship Wrestling, based out of DFW in the 70s/80s. The move consists of an open-hand fist, spread out like an animal’s claw, which is used to exert pressure on the opponent’s face until they’re backed on to the ring floor in submission. But it’s also a father’s powerful, deadly grip on all of his sons, and it clamps down on the psyche of all Texas men born into such a culture: don’t talk about your pain; bury it. Young stars Harris Dickinson (Murder at the End of the World), Jeremy Allen White (The Bear), and newcomer Stanley Simons all deliver incredibly tender, nuanced performances as David Von Erich, Kerry Von Erich, and Mike Von Erich, respectively, but it’s Zac Efron’s picture: as Kevin Von Erich, he plays the eldest son, and the one burdened with the heartbreak of an entire family. The actor is only 36, but it seems as if he’s lived a lifetime: after years of stardom as one of Disney Channel’s most successful graduates, he shattered his jaw in a gruesome accident in 2013, requiring extensive surgery that’s noticeably altered his jawline. There’s been constant speculation and (pretty cruel) jokes in the public discourse in recent years over his visibly marred visage, and there’s a beautiful, damaged physicality and public discomfort in Efron’s take on Kevin that is such a poignant conflation of subject/performer. It’s a triumphant return for the (underrated) leading man, who last impressed in a small part in Harmony Korine’s (also underrated) 2019 comedy The Beach Bum. This is Zac Efron country!

The Iron Claw (2023) is in theaters now.

Scarecrow (1973)

Director: Jerry Schatzberg

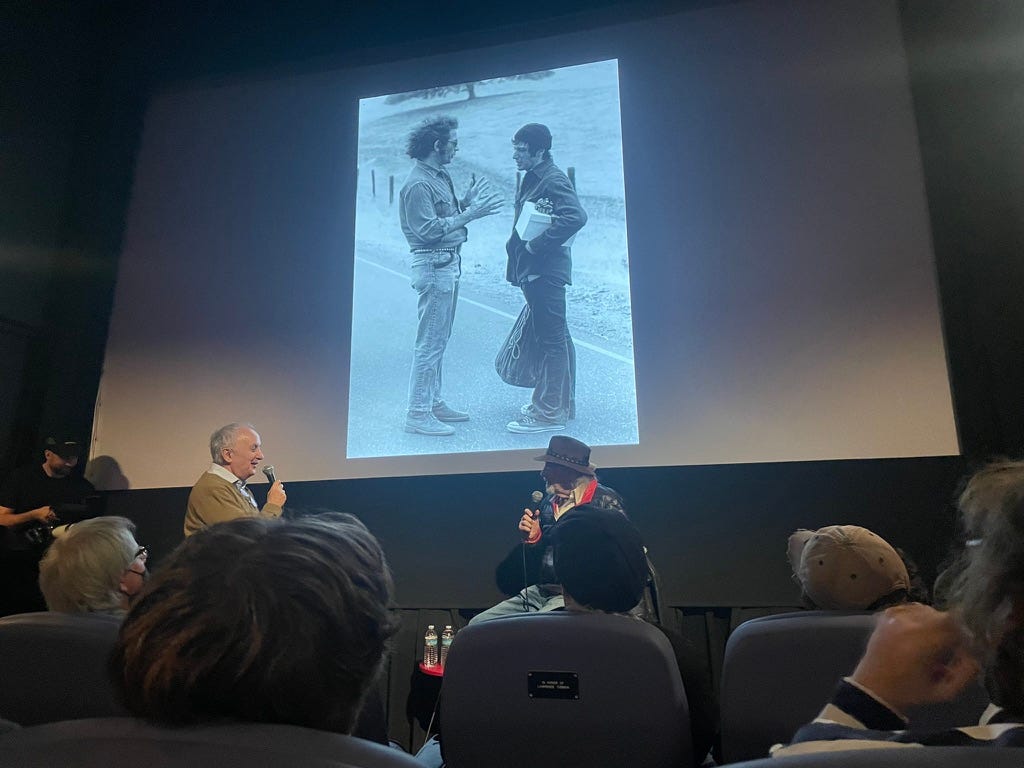

“You make people laugh, they can’t stay mad at you.”

In February 1969, Al Pacino, a student of Lee Strasberg at the Actor’s Studio, made his Broadway debut with Don Petersen’s play Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie? Photographer (and burgeoning director) Jerry Schatzberg saw Pacino in this role, and immediately felt that he’d be the perfect fit for the lead role in his next feature film, The Panic in Needle Park (1971). Pacino was cast, and this first starring role garnered the young actor acclaim, bringing him to the attention of Francis Ford Coppola, who would go on to cast Pacino in The Godfather (1972). After that, Pacino was a bonafide star, and the rest is history. At a December Q&A screening of Schatzberg’s second film, Scarecrow, at Film Forum in New York (which I was lucky enough to attend), the filmmaker spoke of sending footage of Pacino in Panic at Needle Park over to Coppola at his request for more material from the young actor. It’s safe to say that Schatzberg “discovered” Pacino for film, and when it came time to make his next (extremely low budget) movie, he only wanted to work with Pacino and (non-Method performer) Gene Hackman, fresh off his 1971 Best Actor win for The French Connection. A contrivance of timing worked out so that Pacino was able to make Scarecrow before he became unattainable as an actor, but the film came out after The Godfather, making it a strange curio wedged firmly in between career-defining work in The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974). It’s less well-known, obviously, than either of those films — despite winning the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film at Cannes, the proto-Palme d’Or — but it might contain Pacino’s greatest screen performance. Made in the slight window before megastardom, Pacino is unburdened by expectation to act as “Pacino” the volatile, complex leading man. His performance — as a wise-cracking vagabond, just out of prison — is somehow both headier and lighter than his later on screen performances, and he has a charged, potent chemistry with co-star Hackman, fantastic as always, who plays an ex-sailor he meets on the road. Like Midnight Cowboy (1969), there’s a lot of subtext here regarding the dynamic between the two men (both coming out of homosocial environments), but unlike Midnight Cowboy, there’s no self-consciousness evident in the performances: all the seams are invisible, and the film relishes in moments of quiet ambiguity. Shot by legendary cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, who created some of the most indelible images of the American landscape (in films like McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Deliverance, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and The Deer Hunter, to name just a few), this is a beautiful little movie — with a show-stopping single-scene turn from stage actress Penelope Allen — that deserves to be on any list of the best films of the 1970s.

Scarecrow (1973) is available to rent on digital platforms.

The Holdovers (2023)

Director: Alexander Payne

My withered Grinch heart grew three sizes larger towards indie filmmaker Alexander Payne with this delightful coming-of-age dramedy, set at a fictional New England boarding school in 1970, which made me laugh more than any other film in recent memory. Full disclosure: I hated Sideways (2004). I hated The Descendants (2011). I hated Nebraska (2013). I don’t even really like Election (1999), if I’m being totally honest! But artists can always surprise you, and this is the year I ate total crow for my prior dismissal of the longtime writer/director, towards whom I now feel nothing but good will in the new year. Adapting an airtight script by writer David Hemingson — who based his screenplay on his own experiences at New England boarding school — Payne delivers an American spin on Anthony Asquith’s The Browning Version (1951), which is one of my all-time favorite films. A fantastic Paul Giamatti, reuniting with his Sideways director, plays a deeply disliked professor at an all-boys boarding school whose prickly personality and strict teaching style makes him unpopular with students (as well as his fellow staff). Having nowhere to go for Christmas, he’s charged with chaperoning a group of “holdovers,” or students who will be staying on campus for the duration of the holiday season. Soon enough, he finds himself with just one charge: a wiseass young man (played by newcomer Dominic Sessa), with whom he develops a curious bond. They’re joined by the school’s cafeteria manager (Da'Vine Joy Randolph, transcendent), who is mourning the recent death of her son in Vietnam (the attendees of the boarding school, belonging to the rich elite, are likely going to be sheltered from such a fate, as full-time college students could not be drafted). It’s an unusual trio, and their unusual cohabitation puts them at odds (and brings them together) in the cold New England winter. Hysterical and heart-breaking in equal turns, this is a new instant seasonal classic, anchored by three truly masterful leading performances. Dominic Sessa is a star!

The Holdovers (2023) is streaming on Peacock.

Nixon (1995)

Director: Oliver Stone

The 20th century lefty can't help but have begrudging respect for Richard Milhous Nixon — the neocon architect who weaponized an intelligence network and military to pursue his insatiable political ambitions, only to be subsumed by his own monster — and Oliver Stone's clear sympathy for this devil might just make this his masterpiece. It’s pretty unfortunate that Stone is a washed-up predator asshole with lizard brain, because once-upon-a-time, he really could make some interesting films. Four years after plunging his foot, messily, into Conspiracy Theory Cinema with biopic JFK (1991), and just one year after kickstarting a whirlwind of controversy with Natural Born Killers (1994), an exhausting film about American Ultraviolence, Stone delivered this flawless biopic about the Original Liberal Boogeyman: Tricky Dick. Nixon is villainous to the point that it’s almost inspiring to the ardent leftist: he gleefully weld the power that was granted to him through a lifetime of dirty politics and progressive fear-mongering (“She’s pink right down to her underwear!” he said of incumbent opponent Helen Gahagan Douglas in their 1950 U.S. Senate race, leading her to first brand him “Tricky Dick”). Sir Anthony Hopkins looks and sounds nothing like Richard Nixon but circumvents this by bringing all of his Royal Academy of the Dramatic Arts training to play the politician as if he was in a Shakespearean play; he's the perfect neoliberal decepticon and had me eating out of the palm of his hand. A staggering cast of character actors lends the film its richness, including the late Paul Sorvino as the (blessedly) late Henry Kissinger, who Nixon’s staff frequently slurs with anti-semitic remarks; my beloved Bob Hoskins as a predatory J. Edgar Hoover, who Nixon’s staff frequently slurs with homophobic remarks; Powers Boothe as Alexander Haig; Madeline Kahn (!) as the loose-lipped Martha Mitchell; and 90s mainstay Joan Allen, simply phenomenal as Dick’s long-suffering wife Pat. Stone’s screenplay, co-written with Christopher Wilkinson and Stephen J. Rievel, uses Nixon’s life (including his creepy, moralizing Quaker mother, realized by Mary Steenburgen) and political career as a springboard for his alternate take on 20th century American history, which is a somewhat fascinating look at the complex intersection between official record, conspiracy, speculation, and artistic license. Unlike JFK, the film begins with an honest disclaimer: the film is "an attempt to understand the truth [...] based on numerous public sources and on an incomplete historical record." We may never know the whole truth behind the Kennedy assassination, COINTELPRO, Cambodia, or the operatic scale of Nixon’s intelligence apparatus (we certainly didn’t know the identity of “Deep Throat” in 1995), but there is a value in rejecting the loose scraps of official narrative thrown to us by the government, especially considering how much they’ve posthumously proven to have lied about the messier bits of maintaining the American Empire. “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person,” Oscar Wilde wrote — an adage borrowed by filmmaker Todd Haynes for his own alternative history biopic, Velvet Goldmine (1998) — “Give him a mask and he'll tell you the truth.”

Nixon (1995) is available to rent on digital platforms.

The Stranger (2022)

Director: Thomas M. Wright

A fall viewing of The Borgias, a must-watch television program for those who like softcore costume dramas and Papal intrigue, has turned me on to British cult actor Sean Harris, who plays a gay assassin on the aforementioned prestige television series. His filmography is full of great performances in weird little films, including this terrific thriller from Australian actor/filmmaker Thomas M. Wright, which suffers from Poorly Named Film Syndrome (rule number one, don’t use an already famous title). We love Australian cinema around these parts, and those guys are always cooking up something; sadly, this little gem got dumped to Netflix and missed my notice entirely. This genuinely unnerving thriller — based on the infamous murder of 13-year old Daniel Morcombe, which resulted in one of Queensland’s biggest manhunts — stars Harris as a transient petty criminal who seemingly joins an organized crime ring, only to get pinged for internal investigation over his criminal record. He’s mentored by a fellow criminal, played by Joel Edgerton, who has been wisely using his Star Wars money to fund interesting creative projects in recent years. But in this film, Things Are Not as They Seem: the weird relationship between the two becomes extremely unstable, manifesting in a number of tense scenes that are indescribably unforgettable. I don’t want to give too much away with this one, so I’ll just make a pitch for it being one of the more interesting films Netflix has distributed in recent years. I love “rat boys,” as I call them: creepy little dudes in film and television who slither along on the fringes of society in their world, unattractive and unloved by all. But Harris’ creation isn’t a mere subterranean creature: he is an aberration, forged through years of subsistence living, festering pathologies, and isolation. He’s off the grid…and off his gourd! Harris, who is so good that I routinely forgot he was just acting, won the AACTA (Australia’s answer to the Academy Awards) for Best Supporting Actor for his performance, beating out Tom Hanks for Elvis (Australia gets it!), which was handed to him by Baz Luhrmann (?).

The Stranger (2022) is streaming on Netflix.

Macbeth (2015)

Director: Justin Kurzel

If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it dozens of times: wild and weird things are happening out in the country/continent of Australia, including flawless Shakespeare adaptations made by the chief minds behind Assassin’s Creed (2016). It’s the ultimate one-for-us/one-for-them grindset: Australian filmmaker Justin Kurzel (The Snowtown Murders) made Macbeth with stars Michael Fassbinder and Marion Cotillard, shot by Adam Arkapaw (The Snowtown Murders, Top of the Lake, True Detective), only to follow it up with a misguided video game adaptation made with those exact same people, which flopped so hard it canceled all plans for a franchise film series of the latter. Well! It’s a shame Kurzel will likely be better known stateside for the failures of Assassin’s Creed rather than the triumphs of Macbeth (2015), because this really is quite a stunning film, even if nobody has ever really heard of it. Although the film competed for the Palme d’Or at Cannes and received near universal critical acclaim, it failed massively at the box office and only maintains a tiny cult reputation amongst people like myself, who spend too much time online researching Shakespearean adaptations. It’s a weird film, and it makes sense that it flopped: an unusual, compelling mix of "star-studded Shakespearean adaptation" and "arthouse action film," this was destined to alienate purists of both genres à la Julie Taymor’s polarizing Titus (1999) or Ralph Fiennes’ Coriolanus (2011). People forget that Shakespearean plays could be incredibly violent! Arkapaw’s camera paints tableaus of striking, solemn imagery, awash in cool, impersonal blues and fiery, blinding reds. Men meet on impersonal, foggy battlefields against the towering mountains of Northumberland, where filming took place outside the walls of Bamburgh Castle. The titular Macbeth (Michael Fassbender), the Thane of Glamis, is a soldier, weary with the burdens of war and goaded by his scheming wife (Marion Cotillard, out damned spot!!) into seizing his place as King of Scotland, by any means necessary, on the prophecy of three witches. A terrific supporting cast of the UK’s finest performers, including David Thewlis (Naked, Harry Potter), Paddy Considine (Dead Man’s Shoes, House of Dragon, Elizabeth Debicki (Widows, The Crown), and the aforementioned Sean Harris, lend real thespian gravitas to this starkly visual rendering of “the Scottish play.”

Macbeth (2015) is streaming on Youtube (free with ads) and is available to rent on digital platforms.

Lan Yu / 藍宇(2001)

Director: Stanley Kwan

As the saying goes, love is timing, and if there were ever a film scene preoccupied with time, it was Hong Kong’s Second New Wave (1984-present), led by visionary directors like Wong Kar-wai, Mabel Cheung, and Stanley Kwan, whose work grappled with the extreme political, social, and cultural upheaval both in mainland China and within formerly British-owned Hong Kong. “From now on, we're friends for one minute,” a character notes, observing a watch, in Days of Being Wild (1990); in Chungking Express (1994), a character looks to expiration dates on canned pineapple to foretell the future of his broken relationship. Both of those films were edited by costume and production designer (and frequent Wong Kar-wai collaborator) William Chang, who is also responsible for the editing, costume design, and production design of this landmark film: Lan Yu, which received a (gorgeous) 4k restoration and re-release in 2021 by Yongning Creative Workshop (in collaboration with L'Immagine Ritrovata and One Cool). Adapted from an anonymous 1998 homoerotic internet novel, the film tells the story of an on-and-off relationship between a closeted, successful middle-aged businessman and a young, impoverished student in Beijing in the late 1980s, which begins as a transactional exchange. Set against a wider backdrop of significant political unrest and cultural change, the film makes subtle references to the transformative events unfurling, including a pivotal reunion in the aftermath of Tiananmen Square (not depicted, but looming large as a marker of post-Mao cultural change and generational shift). Time — which is ambiguous and fluid in the film — slips by, always taken for granted, as the movie tracks the economic boom of China and the redevelopment of its capital. But most of the film unfolds indoors: in apartments, offices, and homes, with characters framed and obfuscated by mirrors and corridors. We see refracted moments of intimacy: dinners, nights, and celebrations, all keeping us from the intensity of the beautiful (but precarious) relationship between the two men. Despite the cultural taboo of homosexuality in mainland China, this vital work of Chinese-language queer cinema eschews stereotypes and predictable beats: the only thing standing in the way of the relationship, which is incredibly fulfilling, is the two lovers themselves, and their larger expectations for their own lives. “We wasted so much time,” as James Ivory wrote for the characters of Call Me By Your Name (2017), a cinematic scion of Lan Yu. Beautifully acted by Hu Jun, a celebrated stage actor in China, and Liu Ye — who won Best Actor at the Golden Horse Awards, which are essentially the Oscars for the Taiwan film industry, for his performance — and filmed in secret in Beijing, without the approval of government censors (due to its frank depiction of gay sex and bare male bodies), Lan Yu has to be one of the most low-key beautiful films I’ve ever seen. Aching! Yearning! Longing! Director Stanley Kwan is one of the openly gay filmmakers in Chinese-language cinema, and he brings a form of radical compassion to this achingly tender melodrama; the film really feels unstuck out of time, ready to meet us at our current cultural moment. It has never been theatrically released in mainland China.

Lan Yu (2001) is streaming on The Criterion Channel.

The Zone of Interest (2023)

Director: Jonathan Glazer

This is the film meant for our current political moment; sadly, its roll-out has not reflected that urgency, and I hope that it receives a proper wide release in the new year. If I’m being honest, I think distributor A24, which seems poorly suited for material like this, deliberately withheld (and undersold) the film due to the current political climate. If you’ve ever questioned how a population can live happily, comfortably adjacent to a group of interned, subjugated, and methodically eradicated peoples, Jonathan Glazer’s jaw-dropping fourth film examines how such distanciation plays out. Set exclusively outside the walls of Auschwitz in occupied Poland, the film follows the family of real-life Nazi Commandant Rudolf Höss, who take up residence in a seized holiday villa adjacent to the concentration camp, which Höss is tasked with overseeing (and “improving,” in scenes of clinical, sterile detachment). Their villa is a lush paradise, awash with verdant gardens full of fresh vegetables and colorful flowers, and the family relishes in the facilities of the home, playing in the garden, swimming in a pool, and traveling down to the river that abuts the property; beyond its walls, the structures of Auschwitz loom large in the background, a sickening visual reminder that the villa residents are committed to ignoring. The family, led by matriarch Sandra Hüller, who also starred in this year’s Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall, pick through and claim the belongings of interred Jews, casually speak of their racial inferiority, and quietly threaten the local Polish staff who cater to their every need. It’s horrifying. It’s banal. Glazer subverts the “Holocaust movie” genre by mostly forgoing the instantly recognizable visual motifs of the atrocities, using disturbing sound design and a philosophical consideration of absence to connote the horrors just out of sight, while forcing us to look true evil dead in the eye. There’s one moment, where our visuals of the Holocaust briefly intersect with the characters’ visuals of the Holocaust, and it’s a cinematic moment I won’t be able to shake off for a long time. To me, this is the most significant American film released last year.

The Zone of Interest (2023) is in select theaters now.