Favorite First Watches of March

(Real and Ersatz) Cowboys, Killers, Flops, and P.I.s (Or All of the Above)

April programming is coming (next week, for sure); in the meantime and between time, here’s a look back at my favorite first watches of March. So many Westerns (just know that I’ll be your shotgun rider ‘til the day I, ‘til the day I die)… and a little too much to say about David Byrne, once again! Let’s get right into it:

True Stories (1986)

Director: David Byrne

“You know, in a couple of years, this'll probably all be built up,” David Byrne narrates from the front seat of his 1985 Chrysler LeBaron Convertible, which he drives through the open swathes of undeveloped land outside the Dallas-Fort Worth area in True Stories (1986), “Although the center of town is pretty old, around the outside, there's been a lot of people moving in. A lot of construction.” He’s right, obviously: in my lifetime, definitely, the Dallas metroplex has been a space of constant development (and redevelopment). It’s a city of perpetual transformation and construction, where money outranks sentimentality and suburban sprawl spirals out of a dead downtown center, trapping people in isolated cul-de-sacs only connected by automobiles. It’s a good place to raise a family, they say, and Dallas is one of the strongest home purchasing markets in the country, routinely attracting new buyers, enticed by jobs and private personal space, even as art and cultural institutions suffer, shutter, and cease to be. What little is available in terms of non-commercial public space is more novelty than necessity and mostly consists of parks, too hot to sit in for half of the year; no community that stretches further than the end of one’s block (or the domain of one’s church of choice). Alternative culture is cannibalized under the guise of craft breweries and redevelopment of historic neighborhoods like Oak Cliff and Deep Ellum, stripping them of their local identity for humorless hipster pastiche and corrugated iron. In Byrne’s True Stories — which was filmed in Dallas and its surrounding suburbs of Allen, McKinney, Mesquite, Midlothian, and Red Oak — a fictional corporation named “Varicorp” is the gushing teat the citizens of “Virgil, Texas” suck from. In real-life Dallas, the teat is any number of generous corporations, corporate benefactors, and beloved private industry. David Byrne didn’t just peg the Dallas metroplex in True Stories: he foretold its fate. Naturally, people hated it: the film was a massive commercial failure on release, though it developed a cult following over the years. Too ahead of its time.

I grew up in Dallas, the son of two newspapermen from The Dallas Morning News (since decimated), and, of course, love the Talking Heads, so I was a pretty easy mark for this film based on personal bias alone. But I didn’t expect to fall so deeply in love with the film’s whole vibe, thanks to outstanding photography by Edward Lachman (who shot iconic indie films like Far from Heaven, Carol, The Virgin Suicides, etc.) and a rich musical tapestry courtesy of ever-idiosyncratic Talking Heads frontman David Byrne, making his directorial debut following the mass success of Talking Heads’ concert film Stop Making Sense. Byrne stars, sort of, as a wandering troubadour (of sorts), who narrates, waxes on Texas history and identity, and introduces stories of other people’s lives as he drives through and around the fictional Virgil, Texas, a small, developing town dwarfed by a single microelectronics factory that is anticipating Texas’ sesquicentennial (which marked 150 years since 1836, when Texas declared independence from Mexico). The most significant character is an unlucky-in-love Varicorp employee (an irrepressible John Goodman), a (physically) big Southern Man with a (figuratively) big heart, who tries in vain to find his true love and memorably sings “People Like Us” from a neon-lit soundstage in a vast field at the film’s final talent show. The film is full of such odd delights — upsetting fashion shows in luxury malls with falling models; lip-synced karaoke competitions; a bed-ridden Swoosie Kurtz, Pushing Daisies icon, who watches television amidst a host of modern appliances mirroring our current moment —a s well as thoughtful sociopolitical insights from Byrne, twisted through the kaleidoscope of his idiosyncratic personal performing style.

Just how cool is this movie? In something that sounds like Spread Lore but is True, All of It: British rock group Radiohead took their name from this scene of Tito Larriva and his norteño band covering the Talking Heads’ song (of the same name, obviously) from the True Stories album:

True Stories (1986) is available to rent on digital platforms.

Heaven’s Gate (1980)

Director: Michael Cimino

Something I love about being a cinephile is that there is always something still out there to see: notions like “classic” and “flop” are slippery and tenuous, shifting across Time and Discourse, particularly when divorced from their own cultural moment. Sometimes, these designations are technical or spiritual: a beautiful restoration, inspired Director’s Cut, or perfect theatrical screening can completely re-frame the way you see a movie…and sometimes, these designations come courtesy of public perception, fought over in marketing departments, the trades, and entertainment media at large. In one such case, it thwarted the release of one of the greatest Westerns of all time, which I would argue is also one of the definitive films on the American Experiment.

One of the most infamous flops of all time, this drop-dead gorgeous epic Western from zeitgeist 70s filmmaker Michael Cimino — who practically had a blank check following the success of Best Picture-winning The Deer Hunter (1978), receiving full creative control over the project — was notorious for its behind-the-scene woes, including an out-of-control budget, which pushed United Artists into bankruptcy; negative reports of the director's obsessive working style, which apparently was on the side of dictatorial; and the considerable neglect and abuse of animals onset, which allegedly led to the introduction of the Humane Society on film sets with live animals. The film couldn't overcome the behind-the-scenes bad press and when it finally did come out, hacked to bits by the studio, it was a massive commercial and critical bomb. The film has definitely been critically reassessed in the years since its botched release simultaneously earned it an Oscar for Art Direction alongside five legitimately offensive “Razzie” nominations (including a win for “Worst Director”) — particularly after Criterion restored and re-released Cimino’s original cut of the film, which clocks in at three hours and 37 minutes. The film even played at Cannes, where it competed for the Palme d’Or. But Cimino's career — and some would argue, the auteurism of the 1970s — never recovered. When you look at the safe, sanitized nature of Hollywood mainstream filmmaking in the 1980s, you begin to really understand the significance of that loss.

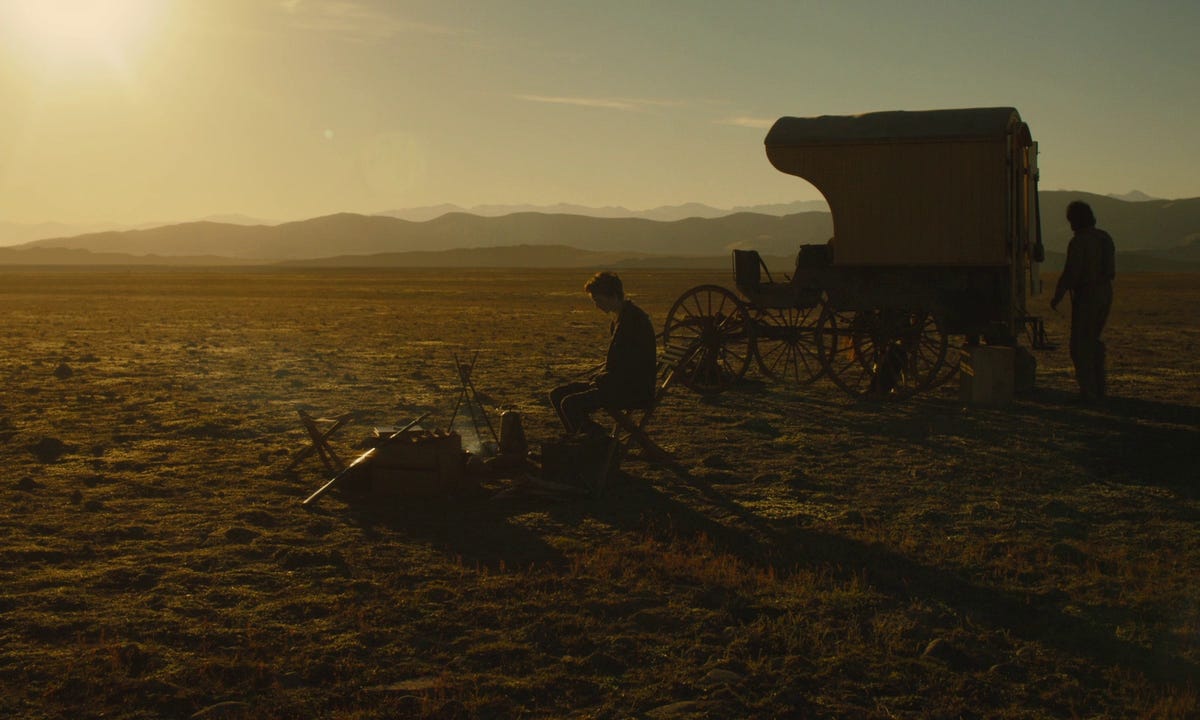

There are movies that move you; inspire you; and mold you…then there are the movies that change the way you see the world….or art…or yourself. “What any true painting touches is an absence - an absence of which without the painting, we might be unaware,” John Berger wrote in The Shape of a Pocket. “And that would be our loss.” There are frames from Heaven’s Gate (1980), a scathing indictment of America’s ever-present war on the vulnerable and impoverished, that rival any painting of the American West, capturing its vast beauty, indifferent terrain, and undeniable allure as few other cinematic experiments have; touching on the sublime. There are shots of the American landscape that are not akin to a painting: framed deliberately, pointedly, to get us to wake the hell up. Beautiful, violent, depressing, and honest, this revisionist epic tells the story of an upper-class Harvard grad (Kris Kristofferson) who re-emerges decades later in 1890s Wyoming, en route to becoming a town marshal. We don’t know how or why his circumstances have re-directed him in this manner, only that he’s playing cowboy after a rather comfortable life. While en route, he is employed by an immigrant community living in Casper, as well as their sheriff (Jeff Bridges), to protect them from the “Wyoming Stock Growers Association,” a collection of rich cattle barons who — in a dastardly effort to basically consolidate a monopoly on the area — organize a “death list” of “undesirables” and “anarchists” to be executed by an army of hired guns with the support of the U.S. government. “They are opposed to anything that would settle and improve things in this country,” a German immigrant (Brad Dourif!) tells an assembly of townspeople through broken English, hoping to persuade the community to take up arms in their own defense when they learn of the imminent arrival of these invading agents. “Or try to make it something more than…cow pasture for Eastern speculators! They advanced the idea that poor people have nothing to say in the affairs of this country!” These violent delights…well, let’s just say they have violent ends. And it’s based on extremely real, fucked-up events in Wyoming’s history.

Shot by legendary cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, The Deer Hunter, etc….), beautifully scored by David Mansfield (who plays a roller-skating fiddler in the film and somehow received a Razzie nomination for “Worst Musical Score,” a category so mind numbingly stupid that they discontinued it in 1985), and starring a jaw-dropping list of generational talents including Christopher Walken (unstoppable here), John Hurt, Sam Waterston (playing the rare baddie!), Isabelle Huppert, and Joseph Cotten, this final cut is one of the most beautiful films I have ever seen and has skyrocketed atop the list of my favorite movies. We have to suffer through so much cinematic slop nowadays because of late-stage capitalism; don’t we deserve to chow down on some real fucking food? We’ll likely never have art this ambitious and so well-funded ever again.

Heaven’s Gate (1980) is streaming on the Criterion Channel.

The Killers (1946)

Director: Robert Siodmak

“Don't ask a dying man to lie his soul into Hell,” a character snarls at another as a man bleeds out in this sexy, nihilistic little film noir, which is just about the perfect combination of all the best tropes of the genre. Told in flashback through half-stories from a number of witness characters, Citizen Kane-style, the film opens on a diner in Brentwood, New Jersey, where two wise-cracking men with guns hold up the joint with a single mission: to kill a man known as “the Swede,” a mysterious drifter who has settled in town to work at the gas station. Played by era hunk Burt Lancaster, in his screen debut, the man has no intention of stopping his assassins: the rest of the film, set after his death, concerns itself with why the hell not. Very loosely developed from Ernest Hemingway’s 1927 short story of the same name, published in Scribner's Magazine, which just focuses on the contract killers, the film turned out to be one of the few film adaptations of Hemingway’s work that the curmudgeonly author actually liked. It’s not hard to see why: tough, gritty, seductive, and gorgeously rendered, this is just a delicious morsel of a movie, thanks to uncredited script work by lefty directors John Huston and Richard Brooks and an all-seeing camera courtesy of former child actor-turned cinematographer Woody Bredell, once accused of being able to "light a football stadium with a single match.” Far too late into the story (and thus far too late into the film, for my taste), we learn of (and meet) a beautiful moll played by Ava Gardner (in her breakthrough performance), one of the all-time-great femme fatales. Seated at a piano while costumed in an iconic black gown by Vera West, she appears on screen to Burt Lancaster like a beautiful siren from some faraway land: dark-haired; dangerous; undeniable. Once you see her, the whole film seems to snap into place. What’s that Frank Miller Sin City series called…A Dame to Kill For? Yeah. You’re going to meet her.

The Killers (1946) is available to rent on digital platforms.

Slow West (2015)

Director: John Maclean

It’s Spread parody at this point to wax on about the creative forces percolating in Australia, which routinely churns out fascinating new films and fully-capable baby stars with the regularity of an old cheapie Hollywood movie studio. One such starlet is beloved beansprout Kodi Smit-McPhee, a former child actor who received an Academy Award nomination in 2021 for his self-assured performance in Jane Campion’s anti-Western, sadomasochistic-tinged The Power of the Dog. But it wasn’t his first introduction to the beats of the Western genre: he previously fronted this phenomenal recent-ish UK/New Zealand co-production from Scottish director John Maclean, making his directorial feature debut (which is still to-date his only feature film, though his next film, Tornado, is allegedly in production). Set in the American West sometime after the Civil War (but shot in present-day New Zealand), the film follows the journey of a 16-year old Scotsman (Smit-McPhee), who travels to Colorado to find his lost love, more-or-less forcefully relocated from Scotland. He’s naive and short-sighted, but his heart is true, and he forms a curious bond with a traveling Irish bounty hunter (Michael Fassbender, who previously collaborated on the director’s 2009 short film Man on a Motorcycle), who agrees to act as his bodyguard and guide for a fee. But all is not as it seems in the uncharted lands of the untamed American landscape, and we’re beholden to individual characters’ perceptions for information, further obscuring notions of “right” and “wrong.” Alliances and ambitions are slippery and ever-changing, and the duo are doggedly pursued by a number of threats, including a vicious bounty hunter played by Australian Asset Ben Mendelsohn, as ambiguous (and vaguely menacing) as always. Shot by the insanely talented Irish cinematographer Robby Ryan, who just won an Academy Award for his work on Poor Things (no comment), this is just about one of the best-looking films in recent memory, but it’s grounded by the performances of its two leading men, who elevate it into something pretty special. If Heaven’s Gate seems daunting at 217 minutes, consider that this movie is 84 minutes. Not such a slow west after all!

Slow West (2015) is streaming on [HBO] Max.

Red River (1948)

Director: Howard Hawks

Men would rather get a posse together to track down and shoot their surrogate son than go to therapy in this (extremely Freudian) Western from legend / icon Howard Hawks, the OG “man’s man” director, which stars John Wayne as a Texas rancher who starts and manages the famed Chisholm Trail alongside a young (and extremely dishy) Montgomery Clift, his more-or-less adopted son who fights for control of it. For those of you who weren’t forced to take an entire year of Texas history in the 6th grade and might not remember, the Chisholm Trail was the first major cattle drive in Texas, which started at a station located along the titular Red River, the northern border of Texas; cowboys drove cattle from various Texas ranches, where there was no market for beef (because of the WAR), up to Kansas City, where it could be put on railroads and distributed on established supply channels. Taking an abstracted approach to the history behind the Texas cattle drive, the film uses the historical event as a mere background to depict inter-generational conflict between two very different men — and the respective values prioritized by both (guess which one has trouble ceding to others’ authority?). This divide is rendered even sharper thanks to the casting of John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, two actors who could not have differed more in style and onscreen persona: Wayne’s shorthand pastiche of laconic masculinity contrasts with Montgomery Clift’s early Method acting style, which feels naturalistic and modern by comparison. They’re two diverging prototypes for American onscreen masculinity, literally duking it out over top billing (while character actor Walter Brennan totally steals it out from under them with masterful manipulation, making Wayne better in the process). The film was Hawks' first outright Western film, and he approached it as a character study, breaking from established conventions of the fairly self-contained genre to infuse elements of melodrama and noir, giving the picture its dark, gritty feel reminiscent of the post-War period. It was a creative decision that helped reinvent the genre for the modern era and proved deeply influential on the screen mythologizing of the American Southwest. Wayne's performance in the film is considered one of his best: John Ford, Wayne's longtime collaborator, apparently commented on seeing the film: "I didn't know the big son of a bitch could act!" I wouldn’t go that far, but he’s not that bad. Elsewhere, the so-called "Hawksian woman" is played by Joanne Dru, self-sacrificing to the point of parody (she's miscast and extremely fabulous). Hawks’ signature (maybe accidental?) homoeroticism is captured in the undeniable sexual tension between Clift and rival gunslinger John Ireland, who says innuendo-laden things like, “There are only two things more beautiful than a good gun: a Swiss watch or a woman from anywhere. Ever had a good... Swiss watch?” It’s hot!

Red River (1948) is streaming on Tubi (free with ad breaks); it can also be watched on Youtube (without ad breaks) here.

The Long Goodbye (1978)

Director: Robert Altman

This time last year, I was hard at work on a program of films documenting the city of Los Angeles in anticipation of our spring trip, which was my first visit to cinema mecca; upon arrival, Vince picked up a black Mustang convertible for us to drive around in. Blasting the Mamas and the Papas, we careened through the sprawling metroplex with the wind in our hair and the sun on our backs. The vibes were immaculate, if the city wasn’t, and I routinely felt like I was in some hard-boiled West Coast yarn for how much we navigated area highways, freeways, mountains, hills, deserts, beaches, and sun-baked city streets. Here’s what I wrote of L.A. at the time:

“Los Angeles, like any American metropolis, is a true city of contrasts: a place of concentrated wealth and opulence that unfurls like a flower the more you pick apart all its layers. The hills bracketing the San Fernando Valley are some of the most beautiful scenery this country has to offer, while the practically unwalkable urban centers are full of bare concrete and tent cities, literally lined up against a backdrop of prosperity. Models, hippies, hipsters, wannabes, Republicans, cinephiles, hucksters, gurus, stoners, progressives, surfers, dreamers, writers, psychopaths, and burnouts have long flocked to (and thrived in) the West Coast metropolis, typically in pursuit of riches, or that amorphous California Dream. “You make money writing on the coast,” New Yorker Dorothy Parker noted of her own move out there, working on dozens of film scripts before her eventual blacklisting. “But that money is like so much compressed snow. It goes so fast it melts in your hand.” A million dreams are born and die in Los Angeles, which make it the perfect setting for film and television and extremely fertile with dramatic and comedic potential.

The Long Goodbye, a darkly funny neo-noir elevated by a revelatory lead performance from 70s alternative heartthrob Elliott Gould (cool as hell), is set in Los Angeles, but it is also about Los Angeles. Unlike films that use city locations for convenience, Altman’s film is interested in the landscape and texture of the city itself, in all its contradictions and co-habitations. It’s almost an Odyssean journey through the City of Dreams: the film might as well be called Models, Hippies, Hipsters, Wannabes, Republicans, Cinephiles, Hucksters, Gurus, Stoners, Progressives, Surfers, Dreamers, Writers, Psychopaths, and Burnouts…seeing as pretty much all those archetypes clash with our intrepid hero, a snarky snoop-for-hire on an altruistic mission to unravel a mystery related to a murdered best friend (Jim Bouton). Cops follow, suspicious, then the criminals the friend was mixed up with. Then a dame (Nina van Pallandt, who in real-life dated the man who forged the infamous fake Howard Hughes autobiography and helped prove his guilt to investigators). Muttering to himself, chewing on a perpetual cigarette, and offering up his signature nonsense catchphrase, “It’s ok by me,” Marlowe travels through the lesser-photographed crevices of the City of Angels in frames beautifully composed by our old friend Vilmos Zsigmond (Heaven’s Gate), haunting neighborhoods like Studio City, Lincoln Heights, Pasadena, and Westwood. Marlowe lives in the penthouse of an apartment in Malibu with his pet cat, overlooking both the valleys beyond and the Manson-esque hippie chicks who lounge nude next door, making it particularly funny when he’s being attacked by police and/or criminals at said location. How can bad things happen in such prime real estate?

A critical and commercial flop on release, The Long Goodbye has since been correctly crowned as one of the greatest films of the 1970s and a signature work in Altman’s filmography. All of the things that made it a polarizing work emblematic of the postmodern ideals of the 1970s film scene on release has made it the classic that it is today: we might call it a revisionist noir, in how it uses the conventions of the genre to deconstruct our assumptions about crime, revenge, and the morality of our mangled, misshapen world. Look at this slob; look at this absolute loser, the film seems to say. He has nothing to hold onto in this world beyond a finicky, vanishing cat. “I'm like cat here, a no-name slob,” as Audrey Hepburn reflects of her own isolation feline in East Coast Opus Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “We belong to nobody, and nobody belongs to us. We don't even belong to each other.”