Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Director: Martin Scorsese

“When this money start coming, we should have known it came with something else.” Martin Scorsese’s epic tale of unassailable white greed in the face of any and all value systems is a riveting, violent rumination on Manifest Destiny and the countess lives thrown away — senselessly, stupidly — in the name of “progress.” White man’s culture, insisted upon as the global standard of civilization, is just excess: clothes, cars, whiskey. Love, family, God… nothing is sacred, really, in the face of such earthly riches. How else can you recognize his chosen people? When one’s worldview relies on the dehumanization and subjugation of others to achieve said riches, it helps to view the people you are exploiting as sub-human (even if that poison slithers in on the guise of patronizing concern): in Killers of the Flower Moon, poor white men assault, murder, gamble, and shoot each other with abandon, but it’s the Osage who are called “savages,” and it’s the Osage who bare the brunt of such Godlessness. In Osage country (which is to say new Osage country, following their forced displacement by the American government), the white man’s forward assault against the natives is less direct than a Wounded Knee-type massacre: it’s far more insidious. It comes as assistance: medicine, banking, paternal concern, Christian doctrines of charity…Charity denotes inferiority, inherently; it’s something given to the needy by the grace (and discretion) of the blessed. In Osage country, “charity” means buying expensive, rare insulin for a diabetic woman, then lacing it with poison when she’s too uppity. Charity kills. Charity has one purpose: to absolve the charitable. Based on David Grann’s acclaimed 2017 nonfiction book, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, Martin Scorsese’s incendiary film adaptation excises the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the book’s central perspective from an FBI agent (played more as a cameo by Jesse Plemons in the film). Instead, the film focuses on the relationship between Osage woman Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone, phenomenal) and former WWI Army cook Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio, transformative), whose rich uncle, William King Hale (Robert De Niro, terrifying), owns a lucrative ranch abutting Osage country. Mollie—like her fellow Osage—sits on a family fortune—which she cannot access, except through a white guardian—built by “liquid gold.” Her mother owns the land rights to a plot of God’s Earth blessed with oil on it, which brings nothing but heartbreak. The Osage are rich and the white men need money, so they begin to systemically marry Osage women and murder them (and members of their families) in cold blood to acquire their fortune, operating under the assumption that no one will care about a trail of dead natives. Ernest, who genuinely comes to care for his wife, finds himself drawn into this deadly plot, even though he’s too stupid and desperate for approval to realize he’s only a pawn in their game. It’s an agonizing, devastating characterization that condemns every single white American at a time when American tax dollars are directly funding the genocide of a subjugated group of people from the comfort of stolen indigenous land and the shield of ignorance befitting a global imperial power’s metropole. It’s an angry film, and it should make you angry. All of this should make you angry. Martin Scorsese is a filmmaker approaching the end of his life and career; he has so much more to say, yet he’s run out of time to say it, which only sharpens the weight of his creative vision. Like his idol, Akira Kurosawa, Scorsese has no intention of dulling his craft in his later years, and the fluid creative machine that exists between him and longstanding editor Thelma Schoonmaker is still delivering on some of the most compelling cinema of the modern era, in direct defiance of cinematic conventions, distribution models, trends, or limitations… including Scorsese’s own mortality.

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) is now in theaters.

Carnival of Souls (1962)

Director: Herk Harvey

A beautiful young woman emerges from the water as the sole survivor of a deadly car crash with friends, only to begin seeing hallucinations of a terrifying entity, which follows her to her new job as a church organist in a town framed by the abandoned grounds of a former carnival. As she’s unable to shake these disturbing visions, she’s drawn to the abandoned fairgrounds for reasons she can’t understand or articulate. In her day-to-day life, she floats like a phantom: she plays the organ and she returns to her boarding house. She can’t make friends, she can’t fall in love. It feels like her entire interior life has been trapped so deep down inside herself that all we can do is look at her blank face and shifting lantern eyes, desperate to understand the mystery of her existence. This stunning independent horror film — the sole feature of director Herk Harvey — was shot (generally on the fly) in Lawrence, Kansas and Salt Lake City. Released on a double bill with Lon Chaney Jr.’s (atrocious looking) The Devil's Messenger (1961), this cheapie horror flick might have gone forgotten entirely after its turn on the drive-in circuit had it not attracted a cult following in the late twentieth century thanks largely to the efforts of film historian Gordon K. Smith, who exhibited a rare print of the film at the USA Film Festival in Dallas in 1989. A subsequent rerelease on the midnight movie circuit, as well as a home video release, helped secure its legacy with cult film fans, enraptured by its haunting atmosphere and curious ambiguity. The film’s simple but haunting visual style incorporates the filmmaker’s love of European art cinema, particularly the works of Ingmar Bergman, making it feel like a true American art film — the ultimate outsider art. This ethereal film is the favorite of a number of famous filmmakers (including David Lynch, George A. Romero, and Lucrecia Martel) and is still referenced in popular culture to this day; recent homages include visual imagery lifted for music videos by Phoebe Bridgers and (somewhat disturbingly) Drake (?).

Carnival of Souls (1962) is streaming on The Criterion Channel, as well as a number of free, ad-based digital platforms, including Tubi, Redbox on Demand, and Plex.

Doctor X (1932)

Director: Michael Curtiz

Back in April 2022, we did a program on Pre-Code cinema, that era in Classic Hollywood moviemaking before the implementation (and enforcement) of the Hays Production Code, which set censorship standards for motion pictures from the early 1930s through the 1950s. As film transitioned into the sound era, films got shorter—and cheaper—than ever before. The "Hollywood Studio System," which governed all filmmaking, streamlined movie-making into an assembly line, ensuring that 60-70 minute films were regularly and frequently released to be shown on full programming bills. Studios began conceiving of increasingly salacious storylines, as well as racy and provocative visuals of sex and violence (including full nudity, realistic gunplay, and scathing cultural critique), that would attract moviegoers. For many in the era, the movies were the only easily accessible form of entertainment: theaters were open late, ran full programs, and cost very little. So it’s really not surprising that the era was ripe with truly gruesome horror fare, including groundbreaking works like Freaks (1932), Dracula (1931), and Frankenstein (1931), as well as a curious pair of films directed by Warner Bros. studio man Michael Curtiz (Casablanca, Mildred Pierce) and shot in striking two-tone Technicolor: Doctor X (1932) and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). Both are playing as part of the Criterion Channel’s Halloween programming Pre-Code Horror, and both are terrific, but there’s just something especially perverse about this first landmark color horror film, which made me really adore it. Set predominantly in two locations: a super spooky lab and a super spooky mansion, the film follows the half-assed efforts of Dr. Jerry Xavier (Lionel Atwill) to clear his institution’s name after it’s definitively linked to a series of disturbing cannibalistic murders. OG Scream Queen Fay Wray is the doctor’s beautiful daughter, who gets caught up with an annoying reporter (Lee Tracy) snooping around for the inside scoop. The plot is all a bit pedestrian, even with its lurid themes, until the film’s final shocking denouement, which is unlike anything you’ve seen in the classic era. Lovingly restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive with assistance from the Film Foundation (thanks, Marty!), the film’s unique coloring, achieved through a marriage of green and red tints, gives the whole thing a garish, artificial feel that’s perfect for pulpy material like this. It would be one of the last films to be made with the two-color Technicolor process; the three-color process (introduced in 1932) would take off in the following years, thanks to its more “accurate” rendering of color, but this film serves as a reminder that accuracy is overrated in the service of a good scare.

Doctor X (1932) is streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Repulsion (1965)

Director: Roman Polanski

Something I’ve really struggled with as a classic film fan—and frankly as a self-taught student of vintage celebrity gossip culture—is the difficult balancing act that being a fan of such art/artists requires, and how best to approach that in my writing. I’ve grappled with a lot of these issues in the course of writing this newsletter: how to discuss films that incorporate tropes of minstrel culture, such as blackface and historical stereotypes; dealing with outdated understandings of gender and sexual identities; lionizing classic film figures while knowing far too much about their personal lives (and personal sins); trying to understand feelings towards a film as one grows and changes oneself, etc. One of the biggest issues is how to handle retrospectives of directors like Roman Polanski—who helmed this particular 1965 atmospheric horror classic—a (once) talented filmmaker and serial predator, whose canonization and institutional protection during his European exile (particularly by the French film industry) helps shield him from the consequences he very much deserves to face for his repeated instances of abuse against underage girls at the height of his power. The difference between Roman Polanski or Woody Allen and say Charlie Chaplin, who did love to wed teenagers, is that these artists are still alive, protected, and financially benefitting from their films, which makes the issue of consuming their films feel rather thorny.

I don’t have the answers, except to reflect that in this particular instance, Polanski’s pathological disdain for young women’s bodily autonomy perhaps helped inform this masterful film about a young French woman (a sublime Catherine Deneuve) whose trauma—formed at the hands of men, dirty rotten men—has completely destabilized her life. I’d heard great things about this film (and Deneuve’s performance), particularly when I was researching our “Women on the Verge” program back in 2021, which covered films that dealt with female trauma and issues of mental health. But I never knew quite how to approach watching it, given that I personally do not want to financially support Polanski in any way, no matter how insignificant. When I spotted a Criterion DVD of Repulsion at a secondhand record shop, it felt like a loophole I could be personally comfortable with taking. I genuinely believe all film, regardless of how much it or its makers may repulse us, should be studied, and this film, despite its provenance, is absolutely worthy of that retrospective. It’s fantastic. The film, written by Polanski with future frequent collaborator Gérard Brach, vaguely follows the beats of Deneuve’s character’s life in London, which has been altered and shaped by some unexplained event in her past. Aloof, quiet, and solitary, she walks the sad, lonely paces of her life to a sparse jazz soundtrack, from the spa where she works to the cramped apartment she shares with her older sister and her sister’s foul boyfriend. When the latter two depart on vacation together, leaving her alone in the apartment, her reality begins to break apart. It’s unclear where the lines of fantasy and reality begin. Simple images—a rabbit carcass, stripped bare and left uncovered in the fridge; a faceless man; cracks appearing in the infrastructure around her—carry masterful weight and convey outright terror that’s all the more unsettling for its ambiguity. As Gilbert Taylor's unforgiving lens becomes increasingly drawn to Deneuve’s haunting profile, the viewer is taken deep into her psychosis, the camera almost cruelly invasive. (The cinematographer received a BAFTA nomination for his efforts). How can you ever be safe, when the worst has already happened to you? How can you keep out the boogeyman, when he resides inside your own mind?

Repulsion (1965) is streaming on a number of free, ad-based digital platforms, including Redbox on Demand, Plex, and Crackle.

Nowhere (1997)

Director: Gregg Araki

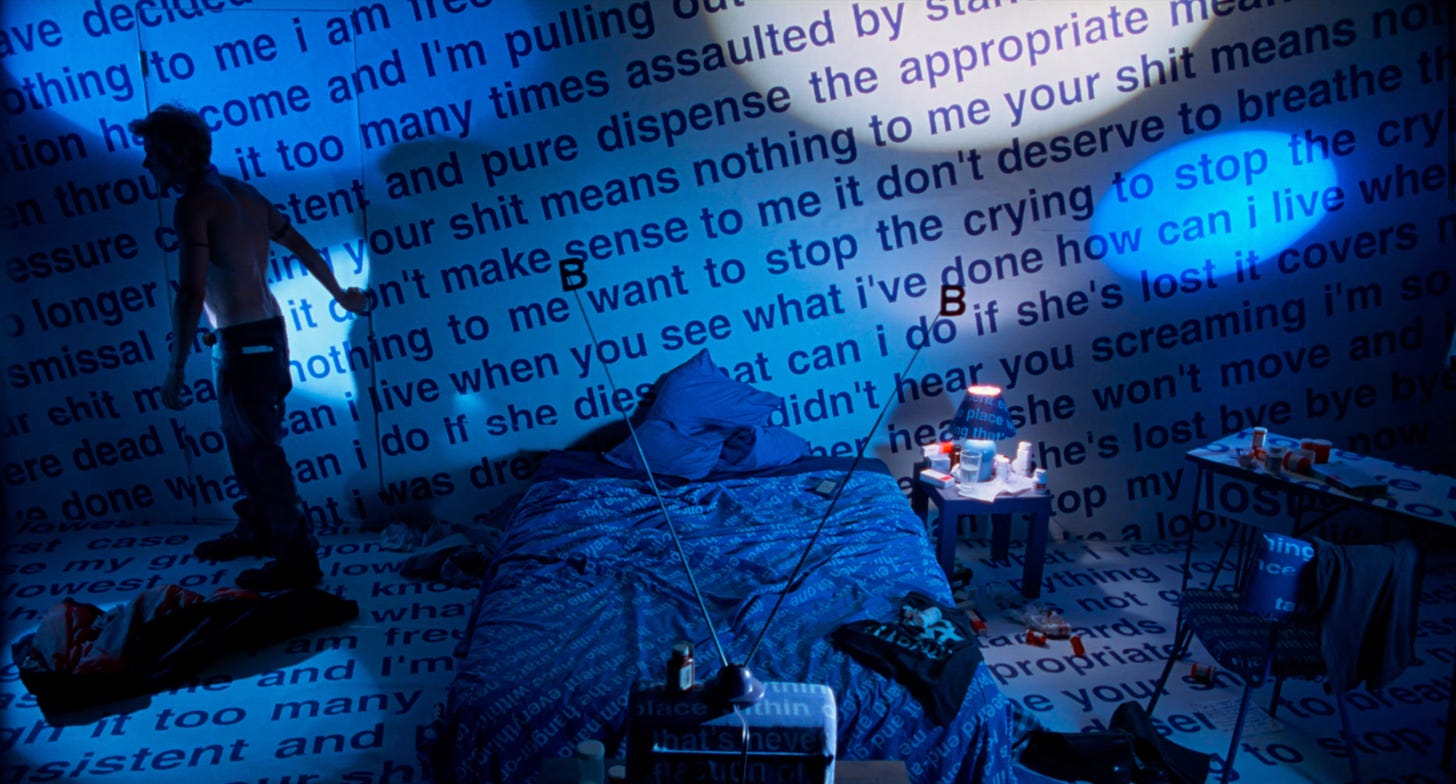

This year, I’ve been working my way through legendary queer punk filmmaker Gregg Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse film trilogy, beginning with the second film in the trilogy, The Doom Generation (1995) and followed by Totally F***ed Up (1993). Nowhere (1997) is the third and final film in the trilogy. All three films, directed by Araki and starring surfer boy muse James Duval (Donnie Darko) were recently restored to their original versions: low quality, censored versions, marred by MPAA-mandated cuts, were only available through circuitous means for several years. Debuting this past September at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, the films were nationally redistributed by Strand Releasing, which specializes in distribution of queer cinema. I saw Doom Generation twice in theaters: once in New York, and once in Los Angeles (so I could see Araki and star James Duval in person), both of which were incredible viewing experiences, and I was lucky enough to catch the Nowhere restoration during its run at the IFC Center in New York. Watching these films with audiences, you really get a sense of how groundbreaking Araki was as a punk soothsayer: his irreverent, angsty, and sex-addled stories of queer teenage ennui and (rightfully earned) nihilism hold up so well, even as we are increasingly told that sex has no place at the cinema (at our Doom Generation screening, Araki lamented that young people were allegedly no longer having sex). For his generation, sex was a radical, liberating act, given how cruelly and callously it was weaponized against his community, framed as a death sentence. The government’s total indifference to the AIDS epidemic decimated and shaped an entire generation of young queer kids, who were told their lives did not matter, then asked to live happy, functioning lives as well-adjusted members of society. As if! The film follows the exploits of a group of teenage LA friends over the course of one increasingly weird day, which may or may not culminate in an alien invasion. The group’s myriad sexual identities and romantic entanglements include open relationships, bisexuality, BDSM, and all manner of arrangements, which bring their own dramas. Think of it as an American version Skins (the only American version of Skins), shot through with political fury and packaged as Gen-X video art. The characters are broad parodies, the language is juvenile, and the film’s striking visual style can’t be contained by its small budget. But it’s a smart, incisive film, with a righteous anger boiling just beneath the surface. We could use some of that anger, given that we’re currently facing the end of the world. Ten years prior to this film, Ronald Reagan —in remarks to the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic— reflected, “It seems to me common sense to recognize that when it comes to stopping the spread of AIDS, medicine and morality teach the same lessons.” They didn’t, and don’t, obviously, but it’s an argument that makes it easier to justify preventable systemic murder of gay people, I suppose. “I feel like I'm sinking deeper and deeper into quicksand... watching everyone around me die a slow, agonizing, death,” Duval’s character opines to the camera in Nowhere. “It's like we all know way down in our souls that our generation is going to witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes. It's in mine, look. I'm doomed. I'm only 18 years-old and I'm totally doomed.”

Nowhere (1997) is currently playing through the end of the month in select theaters. It is otherwise unavailable to stream (legally).

The Devil’s Backbone / El espinazo del diablo (2001)

Director: Guillermo del Toro

“They’re bigger than us. Much stronger, yes. But there are more of us.”

A man lingers, framed in a doorway between a dark interior and the bright arid beyond. He can’t stay there, and he can’t enter the house; he belongs out there, in the desert, a wild thing. Guillermo del Toro’s 2001 allegorical ghost story, The Devil’s Backbone, set during the end of the Spanish Civil War, repeatedly references this famous sequence from John Ford’s The Searchers (1956): in del Toro’s film, the inhabitants of an isolated orphanage often linger in their doorway, looking out at a vast, desolate landscape. It’s 1939, the final year of the war. The orphanage, founded by an antifascist and her dead husband’s doctor friend to help take in the children of the Republican army, acts as a front to secretly harbor gold reserves for their cause. The orphans (and their benefactors) are hiding out in the middle of nowhere as the fighting continues, surviving on scraps and huddling in the cold dark. As the war looms outside, inside the orphanage is a ghost, possibly belonging to a missing orphan boy, and the very real threat of a violent, Fascist groundskeeper who is after the hidden gold. The film takes its title from a deeply disturbing image: an infant floating in a jar, born with its vertebrae exposed. “The devil’s backbone,” the orphanage doctor, a devout anti-fascist, explains to one of the boys. Local superstition states that this condition happens "to children who shouldn’t have been born…nobody’s children.” It’s a lie, he explains: the condition is caused by poverty and disease. The boys are the devil’s backbone of war-torn Spain: disenfranchised to the point of nonexistence. They must (and can) protect each other. If they stand together as compañero, fight as one, they are more powerful than any fascista threat, even the spectre of Francisco Franco’s imminent dictatorship. This lovely, haunting film ends where it began: with a lone adult figure standing in that same orphanage doorway, bound to death. Bound to the past.

The Devil’s Backbone (2001) is streaming on Mubi or available to rent on digital platforms.