July Streaming

Lesbian Cinema, the 90s Black Filmmaking Renaissance, Brad Dourif, James Cagney, and CampCore

Welcome to July, and July streaming, which can be accessed here.

It's summertime, but the living isn't so easy this July: the temperatures are unbearable, the air quality is dangerous, and I'm in a parasocial relationship with the current cast of Love Island [UK], which I've been watching on the projector while hunched over in my air conditioned living room like Howard Hughes, pounding out work against a thumping backdrop of Brit Pop, budgie smugglers, and bants. This season opened with a 2023 house remix of Candi Staton's indelible 1976 hit, "Young Hearts Run Free." I can't stop thinking about these lines from Staton's song:

Oh, young hearts, to yourself be true

Don't be no fool when love really don't love you...

My mind has been especially preoccupied with the limits of love and the power of pop music, in that order, as (it's Cancer season...but also...) I've recently churned out my first piece of published film writing, which is over at Bright Wall/Dark Room for their July issue. BW/DR is one of my favorite places for film criticism, and a place where all my go-to essayists regularly contribute, so I'm beyond excited to have a byline over there. Category is: Travel! My piece is on the essential bit of pre-JFK schlock Where the Boys Are (1960), the Connie Francis-starring film that — through a mid-century pop lens — codified spring beak in America and mythologized cis white hetero femininity as something forged through fear and heartbreak (and the inescable spectre of sexual assault). Unfortunately, I was not able to keep my diatribe about Natalee Holloway, but the references to the music of Lana Del Rey (because it's Cancer season!), the definitive pastiche chanteuse, remain. You can currently watch Where the Boys Are On Demand at TCM through July 30th, or just capture the bittersweet summer poptimist vibes with my writing playlist.

July is typically reserved for my personal favorite streaming themes, as it is my birthday month and writing about things I like is how I have fun. This month: fine-tuning the Lesbian Cinema Canon; a retrospective on the groundbreaking works of black filmmakers in the 1990s; two of the co-stars of Ragtime (1981), and, as an extra special treat: a trip to camp! People often tell me that I give off the energy of someone who went to and worked at summer camp for an extended period of time, and they are completely correct. I simply love to go a-wanderin' along the mountain track!

And speaking of Kamp Kickapoo for Girls....

Lost and Delirious Below Her Mouth, Bound All Over Me: Lesbian and Bi Cinema

Pride Month may be over, but the time is always right to revisit the Lesbian Cinema Canon: originally, I conceived a proper Lesbian film retrospective to coincide with Pride, but the timing didn't work out, so I'm thrilled to finally launch it. Something very curious and specific to queer female cinema has happened in recent years: inarguably, there is more on screen visibility than ever (particularly on the art film scene and in the development of straight-to-streaming fare), but I think it's at the risk of minimizing the groundbreaking works of lesbian film that paved the way (particularly those with especially radical or transgressive visions of queer female sexuality, informed by the limitations of their era). For a long time, continued circulation of lesbian film largely relied on the community itself: lesbian films could make a splash at international film festivals, but rarely did that translate to widespread distribution (or canonization) of queer female films, particularly if they were directed by women (reflecting, I think, the general misogyny of the film industry, whose whims shape film history). In generating a lesbian film retrospective, I wanted to be sure I was consciously including films consumed and loved by actual lesbians, scouring listicles, message boards, and even old printed film guides (the one I referenced cites items' availability on VHS and laserdisc!) to find the perfect mix of lesbian film and television (spoiler: lesbians love Tipping the Velvet from 2002). It's so important to listen to queer media-literate elders, who — having been in the trenches fighting for onscreen depictions of their experiences — will rattle off essential lesbian films no straight critic would even have heard about or bother to contend with (such as the following reflection in the comment section of a listicle: "The Hunger (1983) was one all us lesbians watched in the 80’s. It and Go Fish (1994), Clair[e] of the Moon (1992) and Desert Hearts (1985) were all we had"). I also wanted to be sure I was tracking lesbian cinema across time, dating back to the silent era, in those strange moments before streamlined censorship standards, when expressions of queer sexuality momentarily made their way up onto the silver screen. Then I thought: let's include a little bisexual cinema too, as a treat. Although I love queer subtext, (and I do tend to joke about "bi cinema" being anything with attractive people of both genders) for the purposes of this program I've chosen films that explicitly include and foreground queer female romance. To qualify, you're going to have to make love in gay style... and most of these kids just aren't going to make it

This is Big Business, This is the American Way: The Black Filmmaking Renaissance of the 1990s

Back when we did our actors' showcase for Laurence Fishburne and Wesley Snipes I briefly recapped the period of time in the 1990s when Hollywood decided to finance black filmmakers, thanks to the seismic success of films like Mario van Peebles' New Jack City (1991) and John Singleton's Boyz n the Hood (1991), which demonstrated that there was a market (and need) for black stories on film. Inspired by the program BAM put together a few years ago, Black 90s: A Turning Point, this program highlights the works of black filmmakers at the tail end of the 20th century, as they explored issues of double consciousness, identity, poverty, sexuality, intersectionality, housing discrimination, police brutality, and more. With Hollywood suddenly rushing to cater to a ("burgeoning") "niche" black moviegoing market, it greenlit the careers of visionary filmmakers — like John Singleton, Julie Dash, Ernest Dickerson, Kasi Lemmons, Charles Burnett, Carl Franklin, Mario Van Peebles, F. Gary Gray, Hype Williams, Bill Duke, Darnell Martin, Leslie Harris, among so many others — with new freedom to release black stories starring new black talent, birthing (or cementing) the careers of actors like Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Ice Cube, Nia Long, Tupac, Cuba Gooding Jr., Regina King, Morris Chestnut, Larenz Tate, Samuel L. Jackson, Regina Hall, Delroy Lindo, Queen Latifah, Don Cheadle, Alfre Woodward, Sanaa Lathan, Taye Diggs, Omar Epps, Halle Berry, Keith David, Harold Perrineau, Bokeem Woodbine, and so many more (including the aforementioned Laurence Fishburne and Wesley Snipes). Meanwhile, independent/DIY filmmakers like Cheryl Dunye, Marlon Riggs, Ayoka Chenzira, and Cauleen Smith broke new ground by interrogating black identity within a racist, sexist, and homophobic world order hellbent on crushing their spirit (and their lives). The films of this era feel vital, imbued with an energy and attitude befitting a culture being transformed by the creative output of black artists across all areas of popular culture; at a time of Rodney King, Operation Hammer, "superpredators," and guts to welfare programs, these films are incendiary documents of the issues of their time (or, in the case of comedy classics like House Party (1990,) Boomerang (1992), and B.A.P.S. (1997), just a lot of fun for the black audiences they were conceived directly for). A lot of these films were labeled "hood films" or "hood classics," as they addressed the issues of black urban spaces, ensuring that they persisted in popularity to black movie fans, even as they were forgotten or underserved by the white establishment, which is only now catching up, as works like Menace II Society (1993), Deep Cover (1992), To Sleep with Anger, (1990), and Eve's Bayou (1997) have recently received prestigious Criterion releases and retrospectives. As Hollywood's interest in funding black art waned at the start of the 2000s, these talented directors were systematically shut out of Hollywood, with once-lauded filmmakers finding themselves denied financing (or absorbed into the white mainstream) in a freshly conservative era. Instead of judging these creatives for their later trajectories, we should challenge ourselves to consider the positioning of black talent in Hollywood, which allows a select few individuals in the doors as barriers against criticism, demanding their presence to fill diversity quotas, all the while regularly failing to empower artists to make work on their own terms. Unfortunately, this program does not include the seismic impact of black artists in television in the 90s, which is outside its scope (and worthy of its own full program).

“When if you’re a nice person, it’s easy to be scary as a character in a movie": The Faces and Sounds of Brad Dourif

Since his stunning debut in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), for which he secured an Academy Award nomination, character actor (and Meisner-trained thespian) Brad Dourif has made the most of every bit of screen time he's had, making him one of the definitive "faces" of genre cinema (and, thanks to his long standing work voicing the evil killer doll Chucky in the Child's Play series, one of its definitive voices). He's Wormtongue in Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2012); Doc Cochran in Deadwood (2004-2006); Piter De Vries in David Lynch's Dune (1984). He's the guy you want to see as the creepy scientist experimenting on creatures in your Alien film. He's the guy you don't want tasked with taking down Michael Meyers (in Rob Zombie's cult classic Halloween remakes). His curious performing style and near-theatrical bearing feels like it belongs to another time, as if he's Conrad Veidt or Max Schreck or Lon Chaney, creeping in front of the camera to genuinely unnerve and upset viewers; you can't help but direct your eyes to wherever he is on screen. His go-to collaborator is Deranged Auteur Werner Herzog, and he's a perfect fit as a living oddity in early Lynch films (including a mostly-silent spot in Dennis Hopper's crew in Blue Velvet). He's a full-throated performer, incapable of dialing it back. Ah! Ah! He's acting

Short, somewhat stout, curly-haired, overtly working class, and possessing an almost infantile energy, he was the perfect antithesis to the refined, pouty, and debonair stars of the silent and early sound era, reflecting the energy and vitality of the American hustle (and an angry manifestation of the inequality wrought by the Depression).

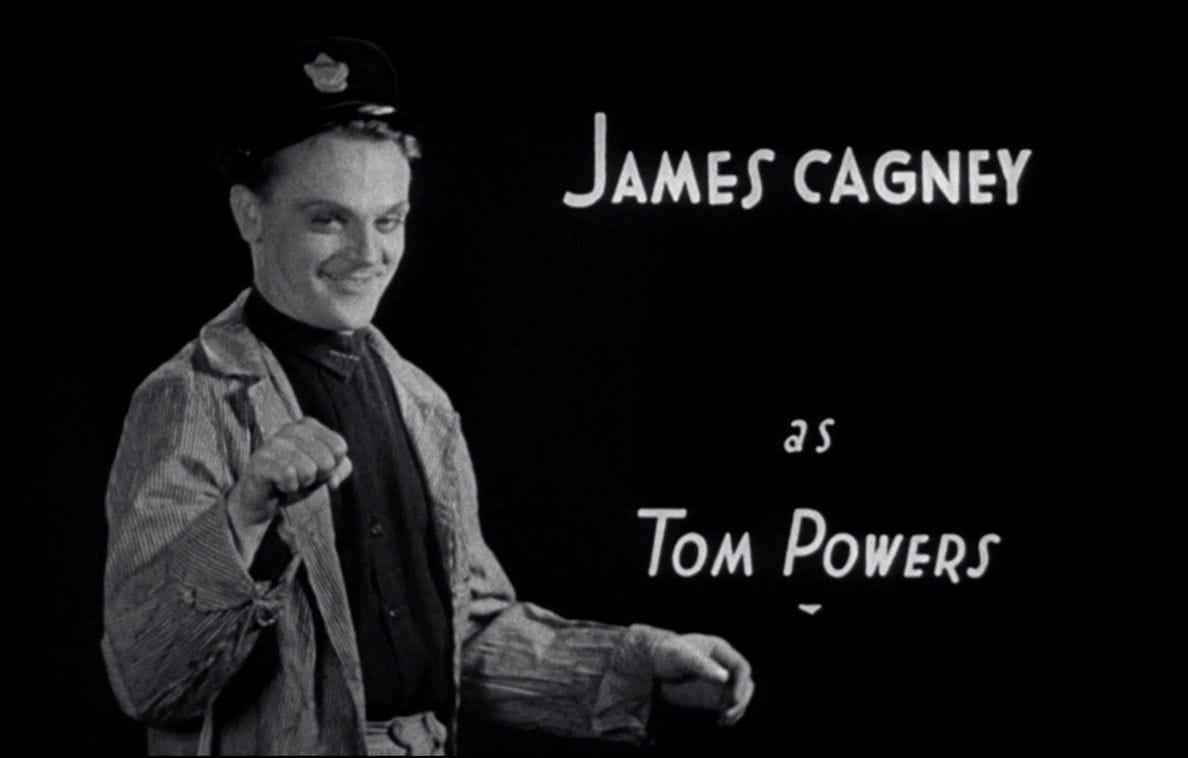

Born on the 4th 17th of July: James Cagney, Just a Song and Dance Man

If you've ever longed to watch a musical starring a guy who seems like he could begin punching people at random, there's only one star of the Classic Hollywood Era for you: [birthday boy] James Cagney. This hoofer-turned-movie star — born in 1899 on the Lower East Side of New York City — became one of the first box office kings of the early sound era, thanks to a hustler's attitude and pathological Depression-era work ethic. His prolific stint at Warner Bros., following his debut in 1930's Sinner's Holiday, included an Oscar win; a gig as president of the Screen Actors' Guild, during which he narrowly avoided a mob hit (via rigged stagelight); and a breach of contract lawsuit against the very home studio that sought to work him like a horse in thankless roles, repetitive iterations of the "tough guy" persona he perfected (then found himself trapped in). Even today, it's hard to articulate the full range of Cagney's appeal as a leading man, as he's still remembered for the (terrifying) gangsters that he played, which were so influenced by the vibrant ethnic-minority community he emerged from. For his role in Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), Cagney affected a hitch in his step and a catchphrase ("Whad'ya hear, whad'ya say?") borrowed from a real-life character he remembered seeing around his neighborhood; in Taxi! (1932), he even speaks Yiddish, which he'd picked up on the streets. Despite being a multi-faceted performer, equally adept at dramatic work, he was largely typecast, even as he fought for better roles and material more befitting the full range of his skills. The actor started as a "hoofer" (era slang for a dance performer that lacks formal training) on Broadway before landing theatrical roles that would bring him to the attention of Hollywood, and he always referred to himself as a "song and dance man." His experiences translate onscreen to a musical physicality that vibrates with energy: when he dances, he looks like a whirling top in motion, all unvarnished talent and proletariat theatricality, his top half rigid and graceful even as his teeny little legs propel him upwards and outwards. When he's not dancing, or transitioning into dancing, he's constantly in motion: pacing, fidgeting, scheming, mugging, cackling, or fighting. He is one of the most compulsively watchable performers of the early studio era: even the most ridiculous of the throwaway, assembly line films he performed in at the height of his career are delightful because of his onscreen persona, a wiseass whose electric charisma made him a sex symbol, even if he's not traditionally regarded as one. Short, somewhat stout, curly-haired, overtly working class, and possessing an almost infantile energy, he was the perfect antithesis to the refined, pouty, and debonair stars of the silent and early sound era, reflecting the energy and vitality of the American hustle (and an angry manifestation of the inequality wrought by the Depression). Sexier than Edward G. Robinson, more memorable than Paul Muni, and pre-dating Humphrey Bogart — who appeared in bit parts in several of his films — James Cagney was the blueprint for unrefined, modern onscreen masculinity, even if it was a total constructed persona, which had to be routinely "discouraged" and "punished" by the Hays office, as he made sociopaths look too appealing (and thus worthy of emulating). Everyone from Bogart to John Garfield to Al Pacino and Robert De Niro owe their onscreen personas to his proto-modern acting style, which really made him the first "bad boy" sex symbol, pre-dating mugs like Robert Mitchum and onscreen rebels like Marlon Brando and James Dean. Unlike so many of his contemporaries, Cagney doesn't seduce, in the traditional sense: he's the wiseass who talks like he already has the girl, thanks to his seemingly limitless confidence. He's exceptional for his time in that he's just like us...he's just...a guy! I just love James Cagney: the way he masterfully flits between Little Lord Fontleroy antics and genuine emotion, as if he's a swiss army knife rather than an actor. In high school, I actually won a cash prize and an honorable mention for an essay contest story I submitted about a young woman who manifests the spirit of James Cagney into personal conversations about her life. (Incidentally, that monetary prize was the same amount I received for my first film essay as a professional writer... My life is actually a flat circle, but I'll unpack that in therapy, not here.) Cagney's earliest films are my favorite, when the whirlwind plots — typical of the era — seem especially eclectic and frenetic in Cagney's presence. Should I watch the one where he's a boxer-turned-health inspector...who beats people up? Or a shanghaied sailor who becomes a newspaper man...who beats people up? Is there any real difference between his nastiest gangsters and his staunchest lawmen? No: he flattens the distance between the two, slyly negating their seeming opposition. When life moves this fast, when violence is this omnipresent, you need a man capable of channeling that raw, unfettered American Id. Cagney won his Oscar for playing George M. Cohan, the scribe behind patriotic jingles like "Yankee Doodle Dandy," "You're a Grand Old Flag," and "Over There," but really he embodied every single aspect of Twentieth Century American Life, from the flag-waving to the carnage: he made it, ma. Top of the world.

Take Only Photographs, Leave Only Footprints: CampCore

At Kickapoo Kamp for Girls in Kerrville, Texas, where I spent thirteen summers as a camper (and then a counselor), there was a near religious object that taunted me every time I took a turn through the kitchen for buffet dinner: a VHS copy of Parent Trap (1998), tucked away on a shelf with a smattering of other films. Every year, one night was set aside as "movie night," and, given that cell phones were banned and with them all exposure to moving media, the movie chosen felt especially significant. Every year we begged: can we PLEASE watch Parent Trap; everyone loves Parent Trap; please don't make us watch Hotel for Dogs (2009), we want to watch Parent Trap....it wasn't until I was a counselor that I learned the awful truth — we would never be able to watch Parent Trap, because the activity shed projector was not compatible with VHS. There's something to be said about a movie that so nails the summer camp experience that it makes you long for summer camp while at summer camp, but that's just the charm of this CampCore classic, which is the finest of all summer camp offerings (including its 1961 progenitor). Camping is perfect kindling for coming-of-age melodrama and horror (consider that the tristate area was so terrified of Cropsey in the late 1970s that two summer camp horror movies, The Burning (1981) and Madman (1981), both inspired by the urban legend, were released in the same year), but it's also great for microdosing silliness: irreverent songs (I recently horrified friends with the katchy kamp song "Cannibal King"), innocuous games, and the kind of self-reflection that only comes about by doing the dumbest possible activities (like competitively creating the longest bra chain). I've put on my summer camp counselor hat (or kerchief — which I received when I was named "honor counselor" for being so good at summer camp), to deliver a round-up of the best summer camp movies and shows, as well as movies (and shows) evocative of a general camping experience. Grab your Bug Juice (it doesn't come in a jar!), rouse your besties for dance war, and do not — under any circumstances — unchain the gentleman tethered to the bottom of Crystal Lake (HE'S FINE DOWN THERE, HE HAS EVERYTHING HE NEEDS).

We've gone fishing for August, but we'll be back in September with fresh programs. In the meantime, subscribe if you're nasty