Noir Wars

Key Noir Moments in the Star Wars Universe (and the essential film noirs they reference)

“Noir wars,” Vince — my partner and intrepid editor — said, one evening, so confidently, into the peaceful silence of our shared living space. “Noir wars.”

Like most things he says, I enjoyed and then promptly dismissed this idea as a bit of true silliness, but he was completely serious. He insisted I go forth with — and properly credit him for — Noir Wars, a round-up of the best noir moments in Star Wars, tying into this month’s film noir-focused streaming program on The Spread. He knows me too well, because by that evening, I had a folder full of screenshots on my desktop and was dragging my aging nerd carcass around the apartment singing the phrase “Noir Wars” in the style of Bill Murray’s lounge singer on Saturday Night Live.

Yes, it’s Noir Wars! Cue the opening crawl:

At the dawn of the fall of the Galactic Republic, a great darkness has fallen over the capital planet of Coruscant and confounded the Jedi Council, whose professed impartiality and naive trust in the Force blinds them to the increasing corruption and volatility of the Galactic Senate, now controlled by Chancellor Palpatine! How will George Lucas, filmmaker and custodian of this world, convey this complex idea to the (mostly) children who watch his movies? What he’s always done with his Star Wars movies: borrow from the past and retool it for the present!

Star Wars, throughout its run, has incorporated the aesthetics and mythologies of the film noir genre to achieve Lucas’ (extremely depressing) creative vision of a galaxy shaped by crushing totalitarianism, codified by a constant interplay of light/dark (or good vs. evil). The definition of "film noir" is sticky, but built on a number of recognizable signifiers: femme fatales; shadowy, foggy streets; masculine antiheroes, broken and hardened by the world; guns; plays of light and shadow and chiaroscuro lighting. Noir is a vibe, achieved through audience recognition of such symbols, but it's also a mode or critical tool: it interrogates systems of power and the effect of such governing structures on everyday human beings, plagued with the tension between survival, success, and one’s own personal code. Noir examines the underbelly of the world but also the darker impulses that constitute the human psyche: greed, lust, wrath, and pride.

Famously, George Lucas — who studied at one of the first American film programs at the University of Southern California — drew from his love of classic cinema and vintage popular culture in designing his universe, incorporating the visual cues of classic movies like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Metropolis (1927), old serials like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, as well as the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa, particularly The Hidden Fortress (1958). It would be easier to name the film genres not woven into the look, feel, and story of the original Star Wars film than to cite all its disparate influences, and film noir is no exception. Star Wars might be a space opera borrowing primarily from Eastern philosophies (and aesthetics) and real-life anti-colonial political conflict, but the pulp sensibility that organizes these ideas into easily digestible scenes of conflict between good and evil? That’s noir.

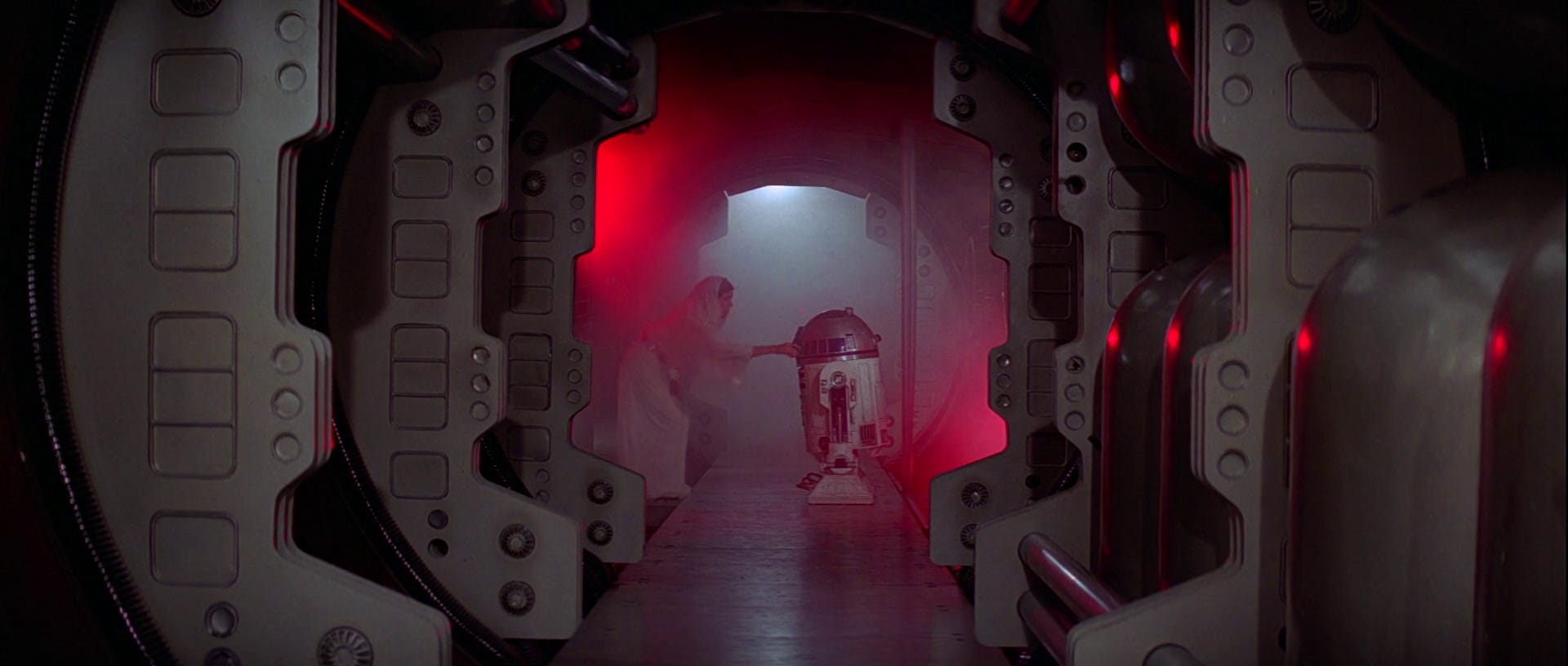

A beautiful Woman in Trouble; concealed identities; hope shrouded in total darkness; wisened smugglers in seedy dens who shoot first; long tunnels and smoky corners of big, impersonal superstructures…motifs of noir can be found throughout the original Star Wars (1977) film, which was such a cultural phenomenon in the 1970s that it begat two subsequent films within the next few years, neither of which Lucas directed (because of stress): The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). All three are tinged (or saturated) with elements of noir. Noir informs the idea of light/darkness warring in the light/dark sides of The Force, the unseen, all-encompassing entity that ties the galaxy together in the universe conceived by Lucas. Star Wars presents the duality of light and dark, but shows us these sides in shades of gray from the moment our hero, Luke Skywalker, inadvertently causes the murder of his family at the hands of the Galactic Empire, kickstarting his journey into the stars. His new mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, appears a kindly old hermit, but manipulates minds and murders in cold blood within hours of their departure. This is what it takes, the film seems to tell us: this is what it takes to survive under fascism.

“Nobody thinks in terms of human beings,” Harry Lime, smuggler and war profiteer, tells Holly Martins amongst the ruins of post-war Vienna in The Third Man (1949). “Governments don't. Why should we? They talk about the people and the proletariat, I talk about the suckers and the mugs - it's the same thing.”

Strange as it may seem, George Lucas has actually played a major part in shaping our contemporary understanding of film noir. In addition to joining the board of the Film Foundation — which facilitates the restoration of classic and international cinema — Lucas has used his mega-millions to personally fund a number of film restorations through the Lucas/Hobson foundation, including vulnerable noir classics Detour (1945), The Letter (1940), Force of Evil (1948), and The Crooked Way (1949). When Lawrence Kasdan, co-writer of The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, set about making his own neo-noir, Body Heat (1981), Lucas came on the project as an uncredited executive producer, providing essential backing to the (then untested) new director. And in 1988, Lucas testified before Congress against the practice of posthumously colorizing old black-and-white films — fighting for the integrity of countless atmospheric black-and-white film noirs in the process (the inherent irony of this is not lost on me).

When it came time to return to his own trilogy in 1999, Lucas seemingly doubled down on all of the elements of the original film that were so personal to him: the anti-imperialist spirit inherent in the Rebel Alliance, the invocation of global politics (including a clear-cut invocation of the Bush administration and its bunk War on Terror, which greased the wheel for increased eradication of our civil liberties), and the cinematic references that initially inspired him to worldbuild in the first place. “It isn't the science, aliens, and all that kind of stuff that I get focused on,” Lucas once told James Cameron. “It's how people react to all those things.”

Lucas had full directorial control over all three films in this prequel trilogy, a choice met with criticism by many who found his scripts to be weak in comparison. But in terms of scope, these films expanded the world far beyond the reach of the original trilogy, eventually birthing a cult animated series — the Clone Wars (2003) — that would receive a garish (but beloved) 3D reimagining and expansion as a film/new television series from Lucas acolyte Dave Filoni (now the Chief Creative Officer of Lucasfilm) in the late aughts, all made in collaboration with Lucas.

As in the original films, elements of noir — and traces of classic noir films — can be found in most subsequent Star Wars properties, with the exception of the sequel trilogy (made after Lucas’ controversial sale of Lucasfilm to Disney in 2012) which has inarguably diluted the creative product that once thrived in relative filmic scarcity through a glut of streaming content no well-adjusted Star Wars fan (hah) could (or maybe should) reasonably parse. Now, with a few exceptions, the old movies that Star Wars products reference are largely… old Star Wars films. For that reason, the sequel trilogy is pretty much excluded here, along with (most) of the Disney Plus original properties, which are (mostly) just awful. No Lucas auteurism here… I just watch what’s in front of me.

So here are all of my favorite echoes of film noir throughout the series, as well as the classic film noirs that clearly served as inspiration. You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy…

The Empire Strikes Back (1980) dir. Irvin Kershner: The Third Man (1949) dir. Carol Reed

AKA War is Hell (and Foggy)

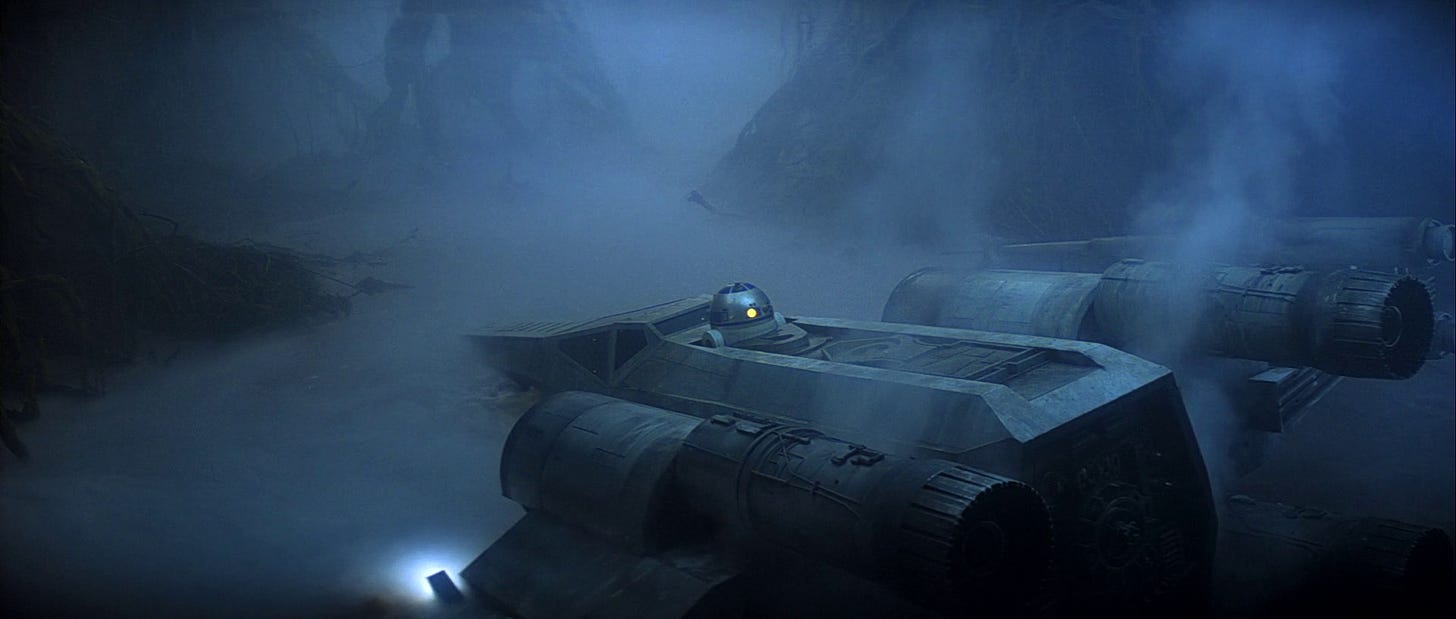

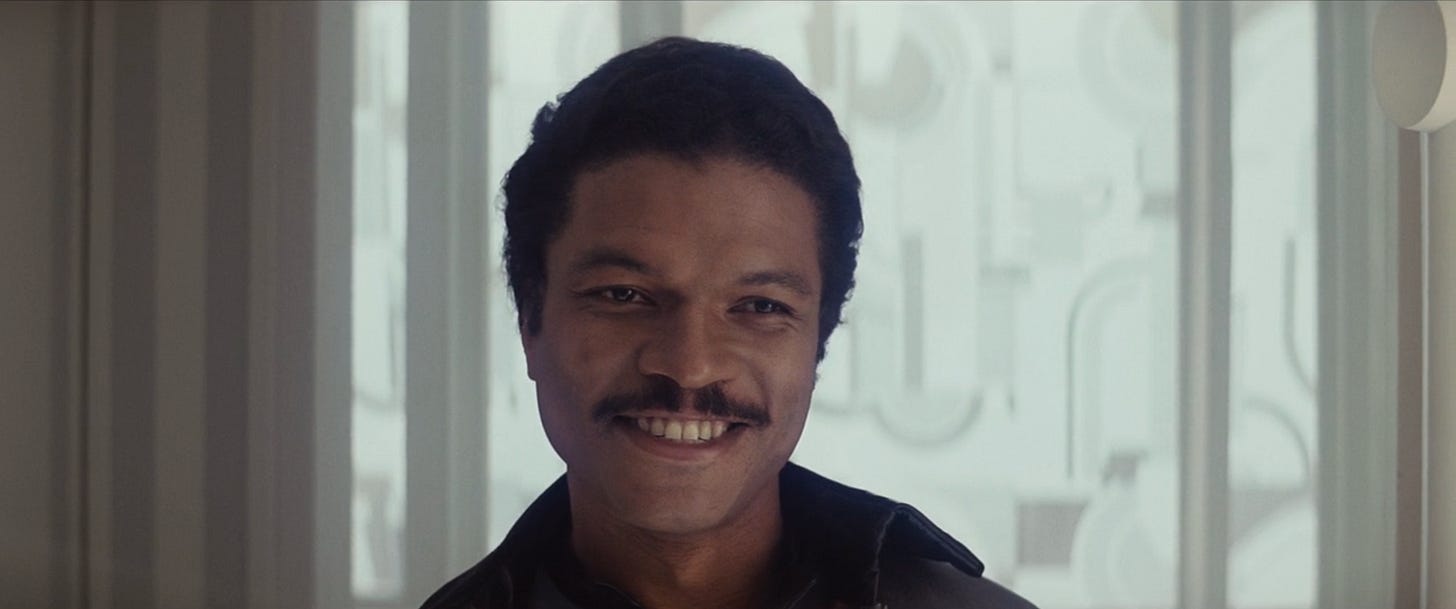

This beloved sequel to the original Star War film is widely regarded as the best standalone film of the Star Wars extended universe, thanks to its formal sophistication, wit, sex appeal, and willingness to delve deep into its protagonist’s psyche. If Star Wars introduces Luke Skywalker as the prototypical big screen hero, Empire looks at all the ways he fails as one: he’s too proud, too attached to his friends, and too impatient to appreciate the (many) nuances of the Force. Worse still, he’s much closer to the Dark Side of the Force than he initially assumes, as he learns a heartbreaking secret about his past. As Luke undergoes exacting Jedi training on the foggy, Vietnam-like planet of Dagobah, our other intrepid heroes fight the full might of the Galactic Empire arsenal across snowy terrains, floating cities, and asteroid fields. Enemies arrive dressed as friends, nothing is what it seems, villains lurk in the fog, and love is suffocated by the poisonous fumes of tyranny.

Co-penned by Lawrence Kasdan, best known for his deconstructions (and reconfigurations) of popular Hollywood genres in films like Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Silverado (1985), and the aforementioned Body Heat (1981), Empire Strikes Back (1980) feels much more sophisticated than Lucas’ original film, with tighter dialogue and a cynical bent that made it my least favorite Star Wars film to watch growing up (I liked the Ewoks of Return of the Jedi), but my favorite to watch as an adult. It undoubtedly helped that star Carrie Fisher worked on the project as a script doctor, and co-star Harrison Ford improvised improvements to Lucas’ stilted dialogue. The film feels tougher, grittier, and just plain sexier for their combined efforts. The film’s most famous exchange, which reads like something out of a world-weary pulp novel, was allegedly improvised by Ford:

“I love you.”

“I know.”

The film’s fatalist vibe and foggy, shadowy interiors evoke the atmospheric noirs of the post-War period, as the world tried to make sense of the carnage, destruction, and senseless violence that ravaged cities like Vienna, the setting for Carol Reed’s 1949 noir classic, The Third Man.

Set (and filmed) against the backdrop of a war-torn, bombed-out Vienna, The Third Man follows Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten), an American pulp novelist, as he reckons with the death of an old friend, Harry Lime (Orson Welles), who he soon learns was a racketeer during the war operating out of Vienna. His racket? Bunk penicillin, which he sold on the black market, causing countless deaths. Pretty bad! Martins becomes embroiled in a conspiracy regarding Lime’s death when he learns that there was an unidentified witness, a “third man,” and sets about investigating. Shuffling between a suspicious police chief (Trevor Howards) and Lime’s grieving girlfriend (Alida Valli), he sets out to uncover the third man, but the truth he uncovers isn’t exactly pleasant.

Written by Graham Greene as a novella and adapted for the screen (with probably some uncredited additions by star Orson Welles), the film is gruff and bleak, with an iconic downer ending that deviates from Greene’s original happier denouement. Cinematographer Robert Krasker, who previously worked with Reed on the James Mason-starring noir Odd Man Out (1947), shot the film in the manner of the German expressionists, with high contrast chiaroscuro lighting, striking visual lines that slash through the frame, Dutch angles, and startling close-ups.

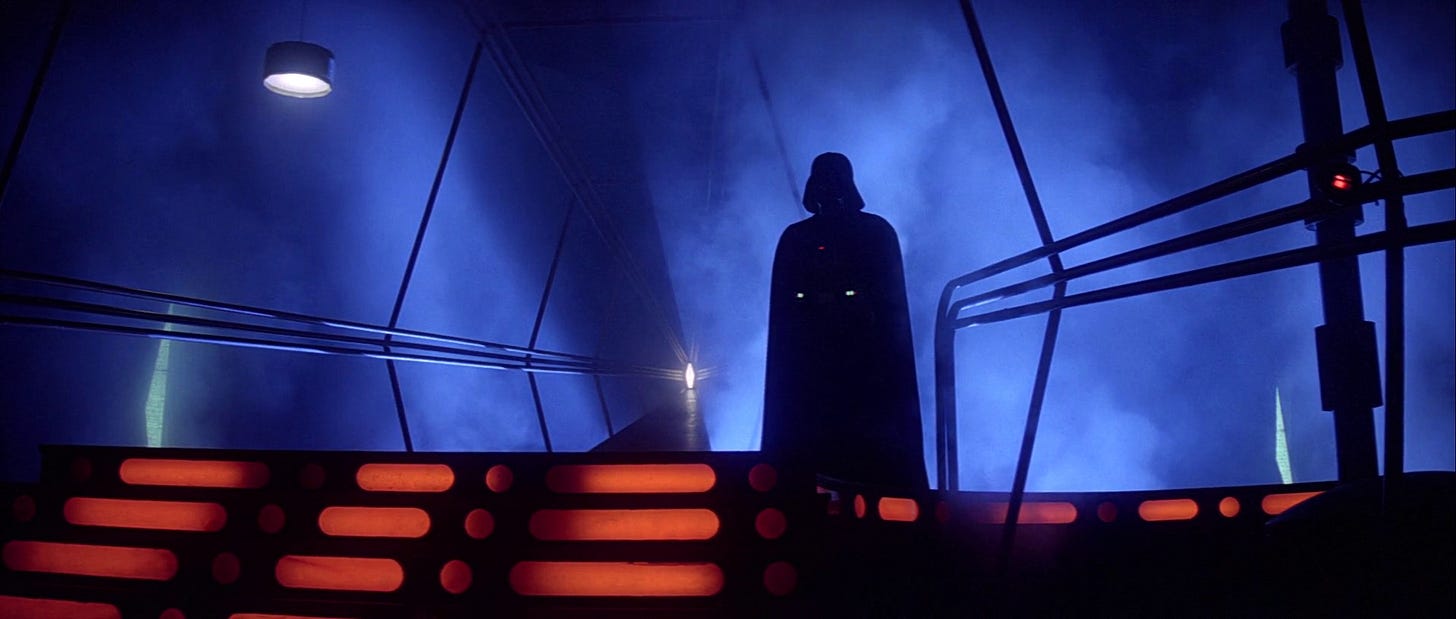

You can see the same aesthetic referenced and reworked in Empire Strikes Back, with its incredible production design by Norman Reynolds (who actually died earlier this year): Reynolds and his team constructed the unforgettable sets of the Bespin carbonite processing center, where the film’s memorable final act takes place. The moody set lighting, which provides high contrast and highlights the characters’ faces against the blue-dominant background, provides the perfect backdrop for a noir-tinged showdown. Here, light falls fractured against our characters’ profiles; steam rises up in gorgeous wafts, evocative of fog; and lightsabers act as key lighting on the faces of Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker as they duel for the first time. They fight in liminal spaces, impersonal and vast; humanoids swallowed by machinery.

Both films hinge on a betrayal by an old comrade, wearing a smile, and both culminate in a chase through the bowels of the city: in The Third Man, it’s the sewer tunnels of Vienna; in Empire Strikes Back, it’s the central air shaft of the floating planet of Bespin. Aesthetically, this allows us to focus on the characters in contrast to the vast, cold, and indifferent spaces they inhabit. Thematically, it illustrates the realities of the larger conflict they’ve been facing: in Vienna and Bespin, these battles are conducted in the shadows, not on battlefields. They’re fighting it out in the literal gutter, which is entirely the point. “We were very free,” a former member of the French Resistance states in The Sorrow and the Pity, Marcel Ophuls’ 1969 documentary about the French Occupation during World War II. “What I'm going to say may sound mean, but I think that to be a Resistant, you had to be maladjusted. We were free in the sense that, as outcasts of society, the organization of society no longer concerned us in the least.”

The Third Man (1949) is available to rent on digital platforms.

Attack of the Clones (2002) dir. George Lucas: Blade Runner (1982) dir. Ridley Scott

AKA In Big Cities, People are Just Flickers of Light

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Spread to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.