Welcome to September and September streaming.

This month, we're leaving summer squarely in the rearview with maybe the most dad-coded collection of streaming programs yet: fitting, because I consulted my own dad in the development of at least one of these programs (I do sometimes rely on the counsel of men). My Baby Boomer father's expertise on rock music of the 20th century is directly proportional to the length of his sideburns in high school (as he explained to me once, the Jesuits forbade beards so he grew his sideburns until they just met in the middle). He taught me (mostly) everything I know about rock music and rock cinema, thanks to his old collection of vinyls, which I tore through as I developed my own musical taste (and a VHS tape of Don't Look Back that was certainly put through the ringer), transforming me into an insufferable mini rockist of my own, one who'd only find renewed interest in the potential for film to track the history of rock music. At 13, my mother told me to stop listening to so much Neil Young or I'd grow up depressed; she was fully right, though I don't know if we can necessarily pin that on Mr. Young. But I still do love him, and I love his performance of "Helpless" in Martin Scorsese's The Last Waltz (1978), and I'm so excited to present our showcase Rock on Film, which includes that film and so many more.

Elsewhere, we've got an Actor's showcase featuring two sort-of leading men, who, as far as I can tell, have only appeared in one film together: Avengers 2: Age of Ultron (2015), which is a sad fact and a real indictment of the limits of our own cultural moment. Also: we're re-opening the vault for a beloved auto film collab, as well as honoring the consecration of marriage on film. So grab your wingtip shoes and let's duck walk through this thing...

You...do know that despite all the computations...you could just dance to that rock 'n' roll station??

A Celebration of the Beginning of the Beginning of the End of the Beginning: Rock on Film

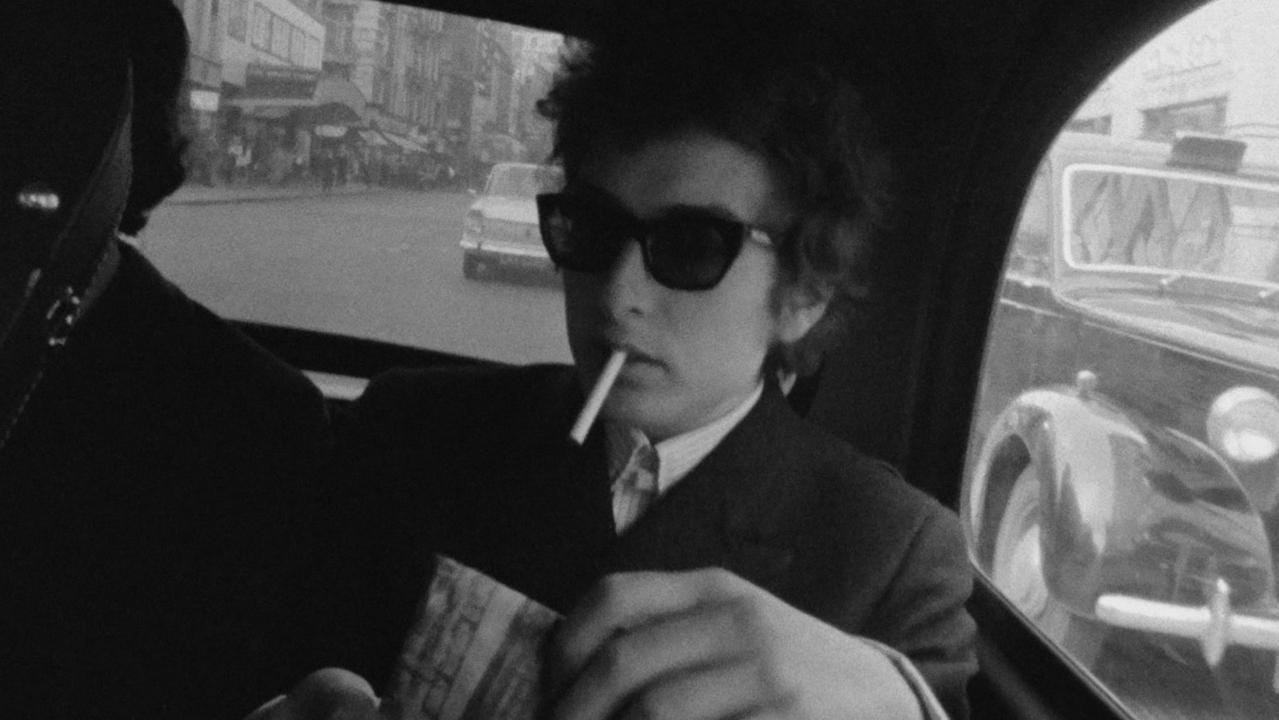

Inspired by a Labor Day program TCM did a few years ago, The End of Summer Tour, this program tracks the depiction of rock music on film, including the rock-and-roll musicals, rockumentaries, concert films, and fictional rock stories that helped consecrate the genre as one of the defining musical styles of the late 20th century and the ultimate symbol of its cultural revolution. Hollywood began trying to capitalize on rock music pretty much as soon as it became popular with white teens, greenlighting a number of concert musicals — really beginning with Rock Around the Clock (1956), a Bill Haley and the Comets showcase released just one year after the song of the same name was used to open the film Blackboard Jungle (1955), a juvenile delinquent drama starring Sidney Poitier, in one of his earliest hits. The film's success paved the way for later artist showcase films like Elvis' Jailhouse Rock (1957) and Chubby Checker's Rock Around the Clock (1961): quickie turnarounds to take the rock idols off of televisions and onto the big screens where they belonged. The history of rock's segregation, however, would be much more pervasive: although Little Richard and Fats Domino led The Girl Can't Help It (1956) — watched by a 16-year old John Lennon, who would be inspired to continue with his own musical aspirations with The Quarrymen — and black pioneers like Chuck Berry and Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers appeared in rock-and-roll musicals like Rock, Rock, Rock! (1956), the genre would soon swiftly be taken over by white men, who'd dominate the face of rock music on film for...well, pretty much up to our current moment! As always, this newsletter strives to diversify its programs as much as possible, but given the structural inequalities of the film industry (and frankly, the music industry) at the birth of rock music, there's always going to be limitations with that. We might look to 1964 as the year that changed everything: in August, A Hard Day's Night, the Beatles' first film (and a progenitor of the modern music video) dropped like a seismic bomb, epitomizing Beatlemania and the British Invasion of the early 1960s. In December, American International Pictures released The T.A.M.I. Show (1964), a concert film that featured a number of popular artists of the time, including an up-and-coming group known as The Rolling Stones; infamously, they appeared after James Brown's barn-burning set, which terrified them (and made them look like amateurs by comparison). The T.A.M.I. Show, directed by Steve Binder — who would go on to direct Elvis' 1968 television comeback special (and also, crucially, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory) — featured a number of popular white and black artists performing alongside each other and really captures the transitory moment when the former, inspired by the latter, reached the point of commercial viability. In 1967, D.A. Pennebaker released his fly-on-the-wall documentary Don't Look Back, filmed in London in 1965 and capturing former folk singer Bob Dylan's transmutation into a "rock and roll martyr" (to borrow terms from Todd Haynes' I'm Not There). Famously, Dylan "went electric" at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; the London tour the film captures began just one month later. Considered a landmark "rockumentary," the film documented Dylan's onstage performances and provided an unvarnished look behind-the-scenes at the most famous lyricist in the world (at his most defensive and brittle). Concert films capturing legendary music festivals would follow: Festival (1967); Monterey Pop (1968); Woodstock (1970) — which employed young editors Thelma Schoomaker and Martin Scorsese — and Gimme Shelter (1970). The latter, of course, filmed by Albert and David Maysles, would capture the horrifying mid-song moment at which a young concert goer was stabbed to death by a Hell's Angel at the infamous Altamont free concert, which many regard as the symbolic death of the Peace & Love era. But rock music, and the rock film, were only just beginning, and we've got them all here (hopefully!): R&B, folk, soul, glam, psychedelia, punk, heavy metal, New Wave (the Stop Making Sense restoration is in theaters September 22nd!), post-punk, pop, disco, and whatever the hell Tom Waits is (don't tell me, I don't care, I just keep listening). From ABBA: The Movie (1977) to Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1979), we've got rock on film in all its eccentricities and contradictions, embracing gerne ambiguities, honoring all film styles, and defying arguments of taste. The only thing that matters is that you play the films very loud.

I'm Superfly T.N.T., I'm the Guns of the Navarone: Samuel L. Jackson, the Pied Piper of Genre Film

He was kicked out of Morehouse college in 1969 for participating in an act of civil disobedience following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., taking the board of trustees — including Martin Luther King Jr.'s father — hostage, in order to force diversification. He later joined, in some capacity, the Black Panther Party, until his mother, following a meeting with the FBI, sent him to LA, seemingly terrified that he would be assassinated. Cut to 2011, when he was named the highest grossing actor of all time by the Guiness Book of Records (which was long before those Avengers movies began printing money). How to make sense of a complete contradiction like Samuel L. Jackson? He doesn't seem like a "one for them, one for me" actor as much as a "one of whatever you got, as many as humanly possible" actor: he's made over 170 films, at which point distinctions of good and bad start to break down. All that matters is that he's completely ubiquitous: the voice, the cadence, the swagger...the way he makes dialogue feel as if he wrote it himself; he's the lodestar of a hyper-referential pop cinema and the ultimate arbiter of cool. After emerging as a distinctive face (and voice) of black cinema in the 1990s, following his appearances in the films of Spike Lee, the actor became an international icon after his breakthrough performance as a poetic heavy in Pulp Fiction (1994), for which he was nominated for his sole competitive Academy Award. The flashy performance lives on in pop culture infamy ("Say what again!"), but it's really more nuanced than people give him credit for, achieving the kind of rare sincerity that makes Tarantino's best characters more than simple pastiche ("I'm trying real hard to be the shepherd"). He's also the film's weathered, still-beating heart, speaking hope and granting grace into a godless world: a real street preacher, dishing out sermons based on a fake bible verse from a Sonny Chiba film. It's his most acclaimed performance, but it's not even his greatest turn in a Quentin Tarantino film: that would come just a few years later, when he played too-cool arms dealer Ordell Robbie in Jackie Brown (1998), probably his best performance. Then, he became a Jedi knight (upending the previously established blue/green and red lore by demanding a purple lightsaber)...then shark food...then Shaft...then a begrudging snake handler...then he Oppenheimer-ed the whole Avengers "thing"...It's not surprising, given his natural charisma, that he became such a figurehead of blockbuster cinema, but it is a bit sad, if only because it makes it sometimes hard to appreciate just what a talented actor he really is. He can veer between comedy and malice with such terrifying ease that you never quite know where you stand when he comes on screen, particularly when that signature charm is weaponized into something sinister and/or deadly —such as in Kasi Lemmons' Eve's Bayou (1997) — masterfully riding tonal ambiguities and slippery genre distinctions — as in the puzzling modern exploitation film Black Snake Moan (2006), where he sings and performs his own songs on guitar. He's a Shakespeare's sonnet, he's Mickey Mouse! He might be one of the few actors I truly believe we need to preserve the head of, Futurama-style, because how do the movies even go on after Sam Jackson?

Return to the Spaderverse: James Spader, Sneering Sex Symbol of Film and (sort of) TV

Back in the nascent days of The Spread (February 2021), we did an abridged retrospective on the films of James Spader, a Brat Pack acolyte-turned-leading man whose sardonic demeanour and proclivity for choosing movies with weird sex made him a reluctant sex symbol and true pioneer of Horny Art Cinema. When I was 13, I hardly realized that Spader's chilling turn as rich villain "Blaine'' in the seminal 1986 John Hughes film Pretty in Pink would be so formative to the development of my own sexuality, but I've been chasing that blend of indifference, disdain, and desire ever since. His pretty-boy looks (and caustic charm) in the 80s almost obscured the terrific leading man he would become, all rogue energy, unsettling vibes, and full-on, straight-up sex appeal. Lately, Vince and I have been watching a lot of David E. Kelley's 2004 hit ABC series Boston Legal (do not do this), which Spader won two Emmys for, and it's curious how much the script relies on Spader as a likable leading man, even as he commits atrocious workplace violations against pretty much everyone employed at this law office. Spader is a pervert and a freak and that's why we love him. After playing a variety of yuppie worms in classics like Baby Boom (1987), Mannequin (1987), and Less Than Zero (1987), he fronted Steven Soderbergh's transgressive debut feature, sex, lies, and videotape (1989), which won him Best Actor at Cannes, where the film also won the Palme d'Or (making Soderbergh the youngest director ever to win the coveted prize). Playing a lost young man who can only get off by videotaping women describing their sexual fantasies, he represented a new kind of leading man: the anti-alpha male, whose eccentricities fuel his isolation but also make him incredibly human and refreshingly vulnerable. He'd play a number of such characters over the years, in some of the most compelling (and groundbreaking) films about sex and sexuality, including David Cronenberg's Crash (1996), where he chases the most dangerous sexual release possible, and Secretary (2002), playing a boss who engages in a (healing) BDSM relationship with his troubled secretary (Maggie Gyllenhaal). Over the years, we lost him to network television, particularly as his looks began to fade, and his cinematic output has been nonexistent since he showed up in Steven Spielberg's Lincoln (2012) and Tommy Lee Jones' The Homesman (2014). He hasn't made an actual film since voicing the villain in Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), but hey, you never know what the future holds (let's put him in a Knives Out, he'd be so good!) Now that The Blacklist is (finally?) over, maybe he will put aside the fedora and return to where we need him most: on the silver screen, making us all deeply uncomfortable. And maybe even a little turned on.

From the Vault: From the First Auto to the Last Race: Autoculture

Way back in the fall of 2021, Friend of the Spread and Professional Writer-in-Hiding Eddy Martinez pitched a programming collaboration, based on his extensive love for (and knowledge) of automobiles and automotive culture. It actually wound up being one of my favorite film programs: Eddy covered the cars, and I sprinkled in some ruminations on the depiction and mythology of the American open road, the significance of the driver's seat, and our cultural fetishization of gruesome car accidents...as a little treat for myself. It's a tremendously extensive program that feels incredibly relevant: Michael Mann's Ferrari (2023) received acclaim out of Venice (do you know how many times Eddy texted me "If you get into one of my cars, you get in to win" since this teaser trailer dropped?); Tom Hardy and Austin Butler are set to dramatize midwest motorcycle gang The Vandals in Jeff Nichols' The Bikeriders (2023), also just out of Venice; and Criterion Channel just released a stellar collection of '70s car films as part of their September programming (which I tore through Labor Day weekend and say who's Le Mans is this?!). So suit up and hop in, we're heading back out on the road with fresh write-ups and even more vehicular cinema. Here's what Eddy previously had to say about our collaboration: Autoculture - a term exploring our communal relationship with the machines that transport us every day. Whether as objects of desire or expressions of success or Sisyphean struggle, automobiles and motorcycles have historically been used as thematic representations of a given society's values, faults, and aspirations, referencing all facets of design, beauty, politics and class. These films have been selected because they point toward the amalgam of intellectual and emotional responses that our vehicles provoke on screen, representing an investigation of exactly why these artful heaps of metal and fiberglass, their pilots, and the roads they travel get under our skin. Go fast, don't die, and keep the rubber side down, kids.

Goin' To The Chapel: Weddings on Film

Just call me Andie MacDowell in a beloved British romantic comedy, because this year alone, I have attended — or will attend — four weddings (including Eddy's imminent November wedding...congratulations, Eddy!)...and no funerals...yet...depends on how all of these weddings go, am I right? Folks — in honor of several friends and/or patrons of the Spread who are engaged, planning a wedding, or staring down the barrel of one, I've compiled a list of the most memorable weddings on film, from the delightful to the disastrous. It's a real sliding scale: not everyone can be Maria von Trapp, walking down the aisle to a begrudging harmonized refrain of a diss track by her (extremely vocal) haters. When you plan a big, life-affirming event, something has to go wrong, and these things are invariably devastating or hilarious, with no possibilities for anything in between. So weddings are (and have been) fertile ground for film narratives (in the case of The Deer Hunter, it's half the damn movie!), and movies have expanded our horizons on what we can expect from a wedding: brides run off, grooms switch last minute, teenage girls written by Mormons marry to have sex with their vampire boyfriends, and ghosts can mistakenly think you're proposing to them if you're in the wrong place at the wrong time. This program catalogs wedding movies — or movies with hefty wedding scenes — as well as the lessons we've gleaned from them. Walking down the aisle to Can't Help Falling in Love, one of the most cloying wedding songs of all time*? Can I suggest ABBA's I Do, I Do, I Do instead? (It always hits). Planning to stage a shoot out with the FBI to escape the mafia? Remember: if it's happening at an Italian wedding, the speeches are before the dinner. Marrying Gérard Depardieu for a green card so you can move into a married couples-only apartment complex? Don't do that. Don't propose at someone else's wedding, don't wear white, don't marry a man (just in case he has seven brothers)...and if you're a bride, I fully support your right to dramatically run away from the altar (but only once, and I'm going to need you to actually, physically run). But if you're a groom, and you dip out on my friend's wedding, I'll get in that black car and run you over myself. Invite me to your wedding, I've watched a lot of movies and distant relatives love me!

*If you're a subscriber of this newsletter and you walked or are about to walk down the aisle to Can't Help Falling in Love: it's a classic love song, one of the great American standards, and I never said this!!

That's all for September! Until next time, keep a clean nose, watch the plainclothes, you don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows!