The Substance and the Age of Ozempic

Body Horror and Dysmorphia, Bravo, and the Big Business of Weight Loss Drugs

This piece includes discussion of eating disorders and body dysmorphia, which may be triggering to some readers.

Earlier this year, finding myself in a rare window of health insurance coverage, I went for a long-overdue physical at a new primary care provider. An extremely brave task, I thought, considering that my last physical ended with that primary care doctor in near-tears, talking for our whole hour about her own gastric bypass surgery, repeating, over and over, with dogged conviction, “I understand, obesity is a disease, it’s a disease.”

I had been hoping she’d check my vital signs. I was looking forward to receiving the little thwap from the hammer that makes your knee jump up. I left without that little comfort, and it was only later, in therapy, that I realized that this was highly unprofessional behavior from a medical doctor.

This year, as I got my vital signs checked and chuckled at the little reflex hammer, I waited with practiced patience for the Fatty Sword of Damocles to fall on my chubby little head, having provided my height and weight and knowing The BMI Conversation wasn’t far behind. But when the topic of weight came up, swiftly and without ceremony, I was met with a new line of inquiry:

“Would you like a shot to help you manage your weight?”

As an avid watcher of the Real Housewives franchise and someone preternaturally drawn to the experiences of older, fabulous women, I’m maybe more tuned into The Ozempic Question than is necessarily healthy: I’ve spent years watching women navigate thorny issues surrounding toxic beauty standards, of which weight is an essential part. And then there’s the gunk swimming around my own head: as someone who has suffered since adolescence with—to put it more euphemistically—disordered eating, I’ve trained myself to disregard hundreds of hours of reality television devoted to weight loss, weight management, eating disorders, and body image issues without issue…more or less.

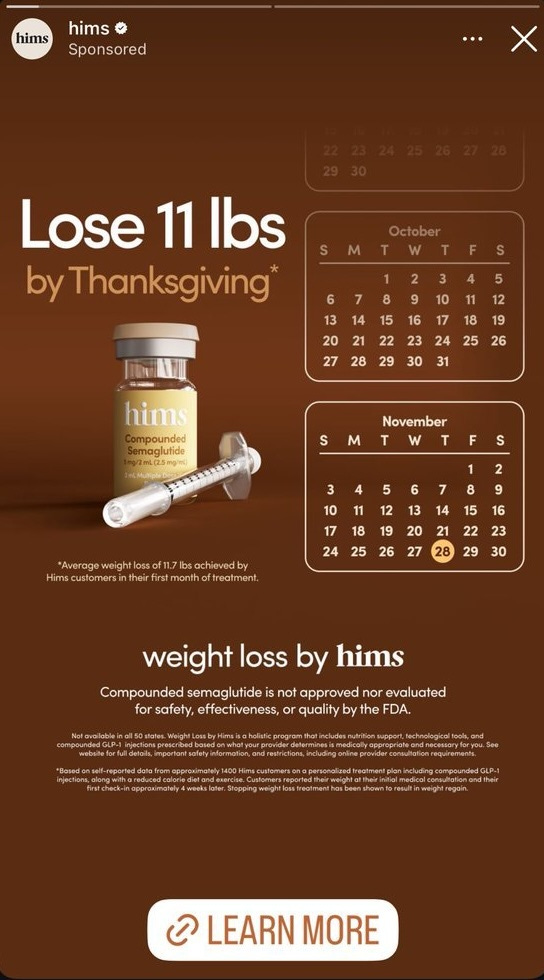

That is, until Ozempic (active ingredient: semaglutide)—a GLP-1 medication originally conceived to treat Type 2 diabetes—began being marketed for weight loss alongside other injectable drugs, including Wegovy (the generic brand my then-insurance company agreed to fill) and Mounjaro (active ingredient: tirzepatide). Now, “compounding pharmacies,” like Ro, Remedy Meds, and Hims & Hers1 have joined the semaglutide business under a legal loophole in the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938: these pharmacies can produce and sell cheap copycat (“compounded”) versions of prescription drugs that are not regulated by the FDA as long as there’s a “shortage” of the prescription. Because Novo Nordisk, the Danish manufacturer of Ozempic and Wegovy, cannot keep up with the surge in demand for the drug, these pharmacies are allowed to peddle their knock-offs…for now. Novo Nordisk recently petitioned the FDA to ban the production of copycat drugs with semaglutides on the grounds that it is too complex a drug to be compounded, and could be potentially risky.2 Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly (maker of Mounjaro and Zepbound) have also reaped the financial rewards of GLP-1 drugs’ explosion in popularity, so they have skin in the game.

My escapist television shows, previously saturated with every imaginable (but seemingly harmless) beauty practice, hoax, and fad, were absolutely transformed by the introduction of Ozempic to upper-middle class women. Suddenly, across every Bravo franchise, every woman larger than the “normative” body size began using Ozempic, or its ilk, to reduce their weight. The topic is broached by producers (and network God, Andy Cohen) with the careful, encouraging language of the legally-minded: you looked great before the Ozempic, and you look great after the Ozempic. Jennifer Fessler, of New Jersey, admitted that she’s still taking a semaglutide despite being hospitalized for an impacted bowel from the medication. Emily Simpson, of Orange County, has discussed her addiction to exercise after losing a bit of weight from a semaglutide, paranoid that she’ll gain it back. Caroline Stanbury, of the Dubai franchise, recounted a colorful incident at The Abbey to Page Six’s podcast, quipping, “If you haven’t projectile vomited on Ozempic, you haven’t lived yet.”

Issues related to body image have manifested in weird and oblique ways on the Real Housewives series, which purports to show the glamorous lives of upper-class women. Of course, the appeal of the series resides in its depiction of just the opposite, showing women at their darkest moments: drunk, sick, angry, gravitating towards criminal behavior and desperate, anti-social displays of id in a bid to stay relevant. In one of the series’ earliest outright depictions of an eating disorder, Jules Wainstein, an underrated “one and done” cast member on the Real Housewives of New York, memorably “cooked” a calzone on a cast outing with a metal fork deliberately wedged inside of it—a move that none of her fellow castmates understood as the kind of disordered eating behavior that “ruins” food so you don’t have to eat it. I’ve never forgotten it, nor Jules’ remarkable honesty about her struggles, making her a trailblazer for a sprawling series that now regularly discusses body image issues. Several women have since spoken candidly about their body image issues, and the compounding factor fame has played in navigating those issues.

Now we have Ozempic.

On the shows, the subject is bandied about in discussion the way Botox once was: as a party trick. A quick fix to a pervasive problem in older age, when excess weight lingers for longer, and in all the “wrong places.” Incidentally, this is also how they are being marketed online by compounded pharmacies. Nowhere, and at no point, does this accompany any discussion of body dysmorphia, nor the psychological impact that losing a massive amount of weight—only to potentially gain it back—can have on an individual.

“I’m completely disconnected from my body,” an anonymous Ozempic user wrote in Slate back in 2023. “I’m running into things; I’m misjudging what fits and what doesn’t. And then, when I walk into a room, people say things like ‘Wow! Look at you!’ They speak to me as if I ran a marathon or wrote a book—only I haven’t done anything…I need to be able to consider my own health, without shame. And I still don’t know how to do that.”

Ozempic hasn’t been on the market as a weight loss drug long enough to confidently predict its longterm impact on users’ physical well-being, though there’s anecdotal evidence of grotesquerie reminiscent of a dicey 2000s fad weight-loss drug, which made you constantly shit your pants. At least one recent lawsuit claims GLP-1 medications caused the emergency removal of a 62-year old woman’s colon, after large sections of it “died” as a result of taking the drugs. Online forums are flush with testimony from anonymous users (and alleged patients) about the drugs’ nasty side effects—including fatigue, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, and a total lack of desire to eat at all—as well as hellish accounts about the compounded versions currently being peddled as “quick-fix” weight-loss solutions.

The compounded versions of these drugs are not evaluated for safety by the Food and Drug Administration, though that has not stopped Hims & Hers from touting the claim that all their compounded drugs are made in “FDA-regulated facilities.” In a scathing report on Hims & Hers’ GLP-1 weight loss program by Hunterbrook Media,3 Dr. Angela Fitch, former director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Weight Center, called the sale of compounded GLP-1 weight loss medication “the largest uncontrolled, unconsented human experiment of our lifetime.”

What scares me more than the unnerving (and disgusting) potential side effects of the latest “miracle drug” is the cultural repositioning of weight—an incredibly complex, multi-faceted problem specific to each individual—as something that can be medicated away, until all human bodies morph into one Great, Perfect Body (or risk social censure). Naturally, that ideal body is thin. It’s a horrific conceit, if you really think about it: the whittling down of all “non-normative” bodies into one perfect specimen, at one perfect size.

“Perhaps any potential risk is worth the reward?” a doctor suggests to his patient in Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man (2024), which tells the story of an unhappy man who takes an experimental medication to “correct” a facial disfigurement caused by neurofibromatosis, causing his face to fall off in clumps. It’s one of two acclaimed films this year—both released on the same day—attempting to tackle our cultural reliance on medicalized body modification, and the experimentation we’re willing to undergo in a gambit to fix the gaping maw inside.

The Substance (2024), French director Coralie Fargeat’s sophomore feature, is perhaps the highest-profile post-Ozempic film4 to date, and, understandably, dredged up a lot of Discourse after its surprise runaway success at the box office this fall (as well as a baffling screenplay win at Cannes in May). The film, which is Mubi’s highest-grossing film to-date, has been something of a water cooler topic online, as well as a meme. As of today, it’s available for streaming on Mubi’s platform. Happy Halloween!

It tells the story of a beautiful, aging starlet, played by Demi Moore, who begins the film running an outdated, Jane Fonda-esque workout television program and encouraging her viewers, mid-workout, to keep working off the fat with a cheery, “You don’t want to be flopping around the beach like a jelly fish!” She is soon fired from her job on the grounds that she’s old and therefore grotesque; the rest of the film is a journey towards her becoming actually grotesque. She learns of an illicit drug called “The Substance,” which allows her, through a gross transformation, to spend a week as a younger, tauter, and “hotter” incarnation of herself (Margaret Qualley), then a week as her old, normal self. “Respect the balance,” the film’s sleek packaging warns. The two incarnations are linked, but don’t seem to share consciousness: they’re wholly separate people, who can’t seem to remotely empathize with either part of themselves. And they are incredibly cruel to one another, to disastrous effect.

A dark body horror comedy that’s more aligned with the gross-out, socially-charged body spectacles of the 1980s like Frank Henenlotter’s Basket Case (1982) and Brian Yuzna’s Society (1989) than a particularly thoughtful film with real, discernible politics, the film was accused by outraged moviegoers of everything from cruelty towards its characters to contempt for its audience to outright misogyny, a response that felt a bit odd given the film’s arch satirical tone.

How could so many filmgoers be so mad at a film so clearly enamored with its own braindead sensibilities?

It’s clear that the film, a fairly obvious allegory for body dysmorphia (“remember you are one”), is being viewed as a treatise on Ozempic culture, which thrives (and relies) on human misery. There’s the film as it exists (an offering of fairly standard, surface-level commentary on toxic beauty culture) and the film people want it to be, which is decidedly mean-spirited; earnestly preoccupied with the mind-numbing exhibition of Margaret Qualley’s flawless ass; contemptuous of women seeking out experimental beauty drugs, rather than sympathetic to their plight; and genuinely mocking the horrific things dysmorphic women do to their bodies. Personally, I don’t think the film is any of those things, and I’m a bit baffled at the heavy-handed responses to it. It’s by no means a perfect film (and its screenplay win at Cannes seems to say more about the French than it does about its particular merits), but it is a fun one, fearlessly led by Moore, one of the brightest lights of the late 20th century, and there’s a gleeful kind of catharsis to its outrageous, bloody ending. How you read that ending, it seems, is how you read the film.

It’s trite to say we need to be kinder to women: obviously, we need to be kinder to women! In a quiet, memorable scene in The Substance, Demi Moore tries to go on a date as her “older” self to boost her self-confidence, but gets stuck comparing herself to the “better” version of herself, and, having put on a face full of makeup, smears it all around, as if she could rub the skin of the body she hates so much right off. It reminded me of a particularly un-fond memory from my twenties, when I had a five-alarm-style meltdown while trying to put on a tricky lip stain and—having smeared it across half of my face trying to fix something repellant I couldn’t identify (myself)—was hours late to a party, only to break down in tears on arrival.

One of the largest obstacles standing in the way of being kinder to women are women themselves, which I think has been the main sticking point in the polarizing reactions to The Substance. There are people who see it as passing blame onto women, and people who see Demi Moore’s reckless flirtation with an incredibly destabilizing drug as a horrible truth reflected back: that they don’t know how to be kinder to themselves through the haze and mania of dysmorphia. And even if they did, the culture is not set up to reward or exalt health, only the “image” of health, however it is attained. In one arresting scene, reminiscent of the worst bouts of destructive eating behaviors I’ve personally experienced, Margaret Qualley attempts to remove a drumstick “left” in her body by her other incarnation, Demi Moore, pulling it out through her belly button in horror before screaming into the void:

I thought it was funny as hell, and, if I’m being totally honest, a way to personally laugh off some of the darker impulses that I kind of hid from everyone in my life when things were really bad, as they have been, in waves. No one cares how you lose the weight, really, as long as you can “respect the balance.” When the seams begin to show, that’s when it just bums people out. And in The Substance, the seams are quite literal.

The body positive movement of the 2010s-2020s has been, largely, a failure, with the pendulum now resolutely swinging in the other direction. Pro-Ana messaging can now be couched in the softer, more positive language of personal preference and acceptance on popular social media platforms, far more accessible than the weight-paranoid teen magazines of my childhood. Men, who face a culture of silence when it comes to issues involving disordered eating and weight loss, are now also being targeted by hawkers of weight loss medications, perhaps more perniciously given the shame that encourages using discreet services like Hims, originally a purveyor of hair loss and erectile dysfunction medications. With the mainstream acceptance of GLP-1 medications as a “miracle drug,” the culture has swung back in the other direction, as if deciding that there’s no excuse to be fat, even if you’re “lazy” (or whatever).

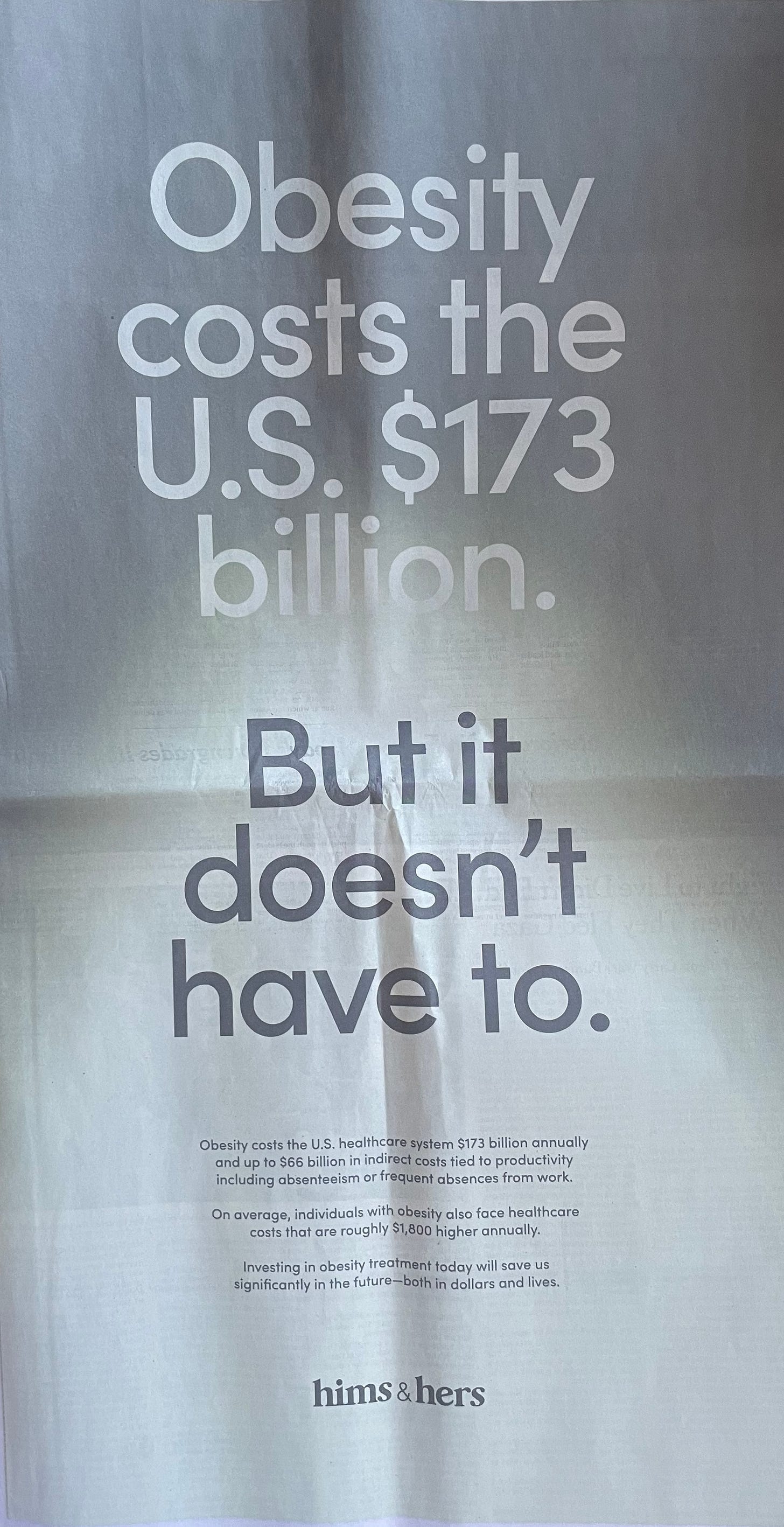

Despite lofty claims that weight loss drugs will help mitigate medical costs related to obesity—a medical designation still determined by BMI, which the American Medical Association has outright stated is racist—there is no evidence (yet) to support this claim, and, in fact, the drugs may have no impact at all on obesity-related medical costs (at least after two years of study). Weight loss drugs are big business: globally, the market for anti-obesity medications is projected to reach $50 billion by 2030. It allows pharmaceutical companies and big tech to reap the rewards of body insecurity, while the culture is excused from addressing any of the structural issues related to global weight gain, including a lack of access to affordable, healthy food; a reduction of publicly accessible space for exercise; and food insecurity caused by global climate change, which drives people towards cheap, highly processed foods.

It’s yet another way Housewives viewership trains the discerning cultural critic to see the writing on the wall: things are going to get very messy, very quickly, and at the end of it all, we will have no more grace for the people struggling with their weight and body image issues. They’ll either keep the weight off, or they won’t. And we’ll all talk about it.

Horror relies on the construction of an “other” to frighten us: in a standard monster feature, this means a hideous, snarling creature that chases normal people around in circles, until one or the other dies. In body horror, the “other” is the hideous thing mapped onto—or drawn out of—the human body; a reflection of our deepest fears and ugliest traits that we’d do anything to conceal from the world. The Substance works because the mechanism behind it is so stupid, so horribly disruptive, so physically disgusting and objectively sketchy, that it feels like something that would absolutely take root in our own culture, which despises fat people, and will do just about anything to get rid of them (or at least keep them in a state of perpetual shame for daring to exist).

I still haven’t decided whether I’m going to, in the immortal words of John Travolta, “GET THE SHOT!” I’ve sort of been avoiding my primary care doctor, because every time I reach out to her about other issues, she just wants to talk about why I haven’t started the Zepbound (Eli Lilly, active ingredient: tirzepatide) she prescribed me in June. If I do take a weight loss medication, it feels like a concession to the baser part of myself that’s caused so much internal harm over the years, which I’m constantly trying to defeat through logic and therapy and exercise and research and reframing. If I take it, it won’t be because I’m concerned about the longterm effects of obesity or my monstrous BMI; it’s not to defeat the great scourge of “absenteeism” and the healthcare costs associated with obesity…it will be because at the end of the day, whatever it takes, all my broken brain has ever wanted, regardless of the harm it engenders, is to be thin. Watching The Substance, I didn’t see an “other.” I only saw myself.

The Substance (2024) is now streaming on Mubi. A Different Man (2024) will be released to VOD platforms on November 5th, 2024.

A very well-known company that—as I’ve learned through personal experience—traps people in costly auto subscriptions with sketchy, deceptive pricing structures and twee start-up aesthetics that mask that you can’t actually get anyone on the phone to help or cancel your subscription “once it’s processed.”

The latest response from the FDA is that they are “working with its state regulatory partners” over concerns related to compounded semaglutide injections.

A fairly new, somewhat dicey-sounding “media arm” of the Hunterbrook hedge fund, which makes trades based on its “investigative journalism.” As far as I can tell, the organization has taken the most critical stance against the company of any media outlet.

Aaron Schimberg’s (lesser-known) film about medicated-away dysmorphia, A Different Man (2024) focuses on a man who is able to “correct” his neurofibromatosis, which causes facial disfigurement, with the help of an experimental drug. The treatment is unable to “correct” away his insecurities, which have festered over several years. (It’s the soul that needs the surgery!)