Happy Valentine’s Day, and welcome to February streaming!

You know, a wise man once sang that “We're living in a world of fools breaking us down, when they all should let us be,” presaging, perhaps, this exact current moment, when love, that unassailable force for good, is our last line of defense against a world determined to break us. Not me, though. Me, I’m a certified loverboy—in the Mariah sense.

Can you feel the love tonight? I certainly can, as I’ve been mainlining so, so many love songs this past month, sifting and searching back through movie history and digging deep into Awards Season Lore for this month’s main program, a microscopic look at an Oscar category so historically fraught and currently imperiled that it has been whittled to a mere nub of its former self ahead of the 97th Academy Awards ceremony.

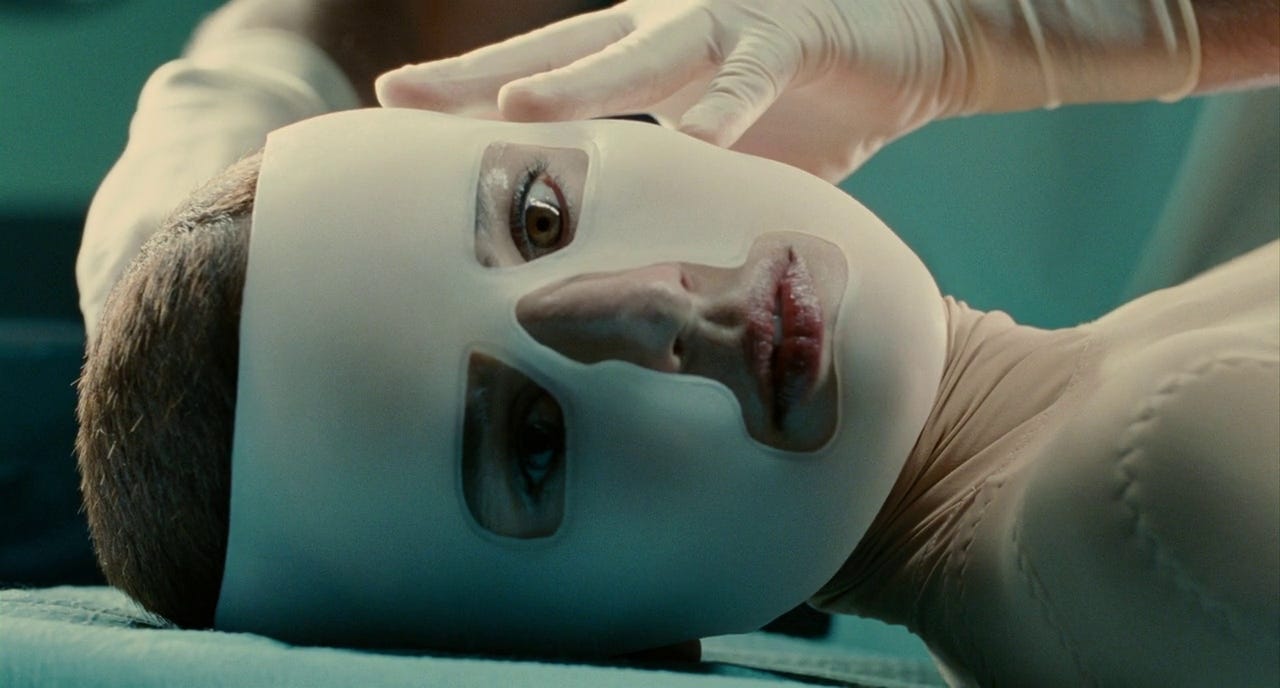

And what better time than right now, when an actor from Spain is kicking up so much dirt this Awards season, to dig into the filmography of one of the country’s greatest sons, whose transposition to Hollywood opened up a messy, messy can of fraught representation politics? He’s played a lot of destructive men, but none so villainous as that time he played a revenge-seeking plastic surgeon in Pedro Almodóvar’s darkest work, and it’s with that firmly in mind that we take a scalpel to the representation of plastic surgery in our media.

The envelope, if you please?

Beautiful Music, Dangerous Rhythm: The Academy Award for Best Original Song

If you were alive and sentient in 2006, you remember “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp,” the unavoidable ear worm from Hustle & Flow (2005)—and the time that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in a move so uncharacteristically cool it feels like a false memory, awarded it the Academy Award for Best Original Song. It was just three years after Eminem’s “Lose Yourself” became the first rap song to claim the award, and a mere decade after Andre 3000 took the stage at the Source Awards to a wall of boos and boldly declared, “The South’s got something to say,” staking a claim for southern hip-hop in an industry obsessed with East Coast / West Coast dichotomies. Southern hip-hop, despite dominating and leading the culture, has had to fight tooth and nail for institutional recognition ever since. Which is why it’s so, so funny that for one beautiful, impossible moment in time, Three 6 Mafia, the pioneering, cult favorite southern trap group out of Memphis, took to Hollywood’s biggest stage alongside Taraji P. Henson to perform their Oscar-nominated hit—and went on to win the award.

The group’s win was a groundbreaking moment for hip-hop at the Oscars—Eminem, famously, did not perform “Lose Yourself” on Oscar night, instead returning, 17 years later, to perform it in 2020—as the Academy’s original song eligibility rules disproportionately punish the musical genre, which relies heavily on sampling and recycling of past sounds. Palpably stoked to be there, Three 6 Mafia’s exuberant reaction to their win is still regarded as one of the greatest Oscar moments of all time (“George Clooney, my favorite man, he showed me love when I first met him!”), and an example of the kind of beautiful synergy that can happen when the Academy dares to be interesting (and relevant) for a change.

Sadly, nothing remotely this cool has happened at the Oscars since—and the comparable moments prior to this can be counted on one hand: specifically, Issac Hayes’ win for the main theme from Shaft (1971), and Paul Jabara’s win for the triumphant, Donna Summer-sung disco hit “Last Dance,” from Thank God It’s Friday (1978). Very few artists of color, actually, have taken home the big award,1 and, generally speaking, the Academy, when confronted with massive cultural change, tends to dig its heels in—take, as example, the year that they awarded Best Original Song to “Talk to the Animals” from Doctor Dolittle (1967) instead of the Simon & Garfunkel-penned “Mrs. Robinson” for The Graduate (1967), a groundbreaking New Hollywood film that garnered seven Oscar nominations (and one win, for director Mike Nichols)…none of them for its music.

The Academy Award for Best Original Song was introduced as a category at the 7th Academy Awards, which honored the films of 1934 and marked the first year that the eligibility period for films coincided with the previous calendar year. Beginning in 1946 (with the 18th Academy Awards), every nominated song would also (in theory) be performed at the ceremony for the Academy’s viewing pleasure—a delightful annual tradition notably excluded from this year’s ceremony, where Emilia Perez is expected to take home the prize (though somehow not for the song on everyone’s lips, “La Vaginoplastia”). It’s a pretty sad state of affairs, and (movie music) politics as usual: in a just world, the award would go to “New Brain” or “Blood on White Satin,” the best faux-pop songs of the year (courtesy of White Lotus composer Cristobal Tapia de Veer), from Smile 2. But if the award simply went to the best original song written directly for inclusion in a motion picture, it wouldn’t be keeping in line with almost a century of Oscar History.

The first-ever Best Original Song winner was “The Continental,” courtesy of Con Conrad (music) and Herb Magidson (lyrics)—a delightful, (seemingly) never-ending song and dance ditty performed in The Gay Divorcee (1934), arguably the greatest Ginger Roger and Fred Astaire musical in terms of all-around quality. The conceit of the category is simple: the Award, honoring the best songs written directly for a film, goes to the songwriters, not the performers who introduce the song, unless the performers have a hand in its creation. Songs must have been written directly for the movie they are introduced in—a point of contention formally settled after seven-time nominee (and two-time winner) Jerome Kern, who won the award for “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” a song that was popularized on wartime radio well before its inclusion in Lady Be Good (1941),2 petitioned the Academy demanding the change—though if you dig through the history of winners and nominees, you’ll learn, as I did, that enforcement of those rules has not always been…steadfast. It was, however, clearly enforced by the time “Come What May,” the iconic “secret song” at the heart of Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! (2001) was deemed ineligible for nomination because it was technically written for—but not used in—Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996), denying us a glossy Oscar Night performance of the song in a post 9/11 landscape when we needed it most.

The unspoken, opaque politics of the category are…exhausting. And seemingly anathema, with obvious exceptions, to fun. Nominations are determined by the songwriters and composers within the Academy (and determined by the scene of the film the song appears in), but winners are chosen by the Academy as a whole. And there’s a whole inside ballgame that’s not without dirty tricks—including at least one known instance of sabotage! Studying the list of nominees and winners (and observing what failed to make the cut), you begin to notice definite patterns about the category, the biggest of which is—for all we joke about the category feeling irrelevant in 2025—that the Oscars have sort of…always been this way.

Consider the 1954 loss of Dean Martin standard “That’s Amore,” practically a prerequisite for future films about the Italian-American experience, to “Secret Love,” a song from Calamity Jane (1953), the Technicolor musical about the famous frontierswoman played by Doris Day, which surely no one, in 1954 or otherwise, was seriously caping for. The following year, perhaps in penance for its prior Italo-phobia, the Academy awarded the prize to the titular theme from Rome-set romantic drama Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) over “The Man That Got Away” from A Star is Born (1954), one of the greatest songs ever written for a movie musical, beautifully sung by Judy Garland for her screen comeback. Frustrating, right? Just wait: two decades later, the Academy wouldn’t even bother nominating the “Theme from New York, New York” (1977)—a Golden Globe-nominated song so iconic, it plays on repeat while you file out of Yankee Stadium [UPDATE: THIS IS NOW NO LONGER THE CASE WHEN IT COMES TO LOSSES]—first introduced by her daughter, Liza Minnelli, in Martin Scorsese’s underrated postmodern musical (more Italo-phobia).

Something critical I learned about the Academy, and myself, in completing this census: the former loves a ballad, while the latter does not (I’ll concede it’s a bias one must overcome, like incorporating ruffage into one’s diet). The category is just rife with ballads, some beautiful and striking, some slow and interminable; yet they seem to regularly ignore the best ballads, like Diane Warren’s Golden Globe-winning “You Haven’t Seen the Last of Me,”3 a fitting swan song for Cher written for Burlesque (2010), or Bruce Springsteen’s stunning title track for The Wrestler (2008), another Golden Globe Best Song winner that failed to scare up even a nomination at the Academy Awards.4 Power ballad “Nobody Does it Better,” the Greatest Bond song of all time (and second ever nominee), lost to “You Light Up My Life,” a corny Debby Boone (her??5) dirge from the forgotten film of the same name—which also blocked “Nobody Does it Better” on the charts and at the Golden Globes and the Grammys that year (evidence of a culture in serious crisis). Actually, some of the worst Bond songs have taken home the top prize—including Sam Smith’s near-formless, forgettable “Writing's on the Wall,”6 while “Live and Let Die,” the first-ever Bond nominee, lost to the moth-eaten title track from The Way We Were (1973). Shirley Bassey’s sinuous performance of “Goldfinger” (1964) wasn’t even nominated, and Duran Duran’s “A View to a Kill” secured only a Golden Globe nomination in an Oscars year that nominated the unspeakably awful original song tacked on to A Chorus Line (1985).

The Academy is never beating the accusations that they hate sex.

In fact, the Academy is never beating the accusations that they don’t know what century it is, let alone what’s happening in music. For every great, fitting win—such as the two times the Academy recognized the considerable contributions of Indian musicians to global cinema, with big wins for “Jai Ho” from Slumdog Millionaire (2008) and “Naatu Naatu” for Tollywood instant-classic RRR (2022)—are head-scratching failures to read the room, like when the Academy spitefully failed to nominate a single track from Saturday Night Fever (1977), a cultural phenomenon that went on to become one of the highest-grossing soundtracks of all time. Another of the highest grossing soundtracks of all time? Purple Rain (1984)…zero nominations. The late Adam Schlesinger, of Fountains of Wayne, penned the greatest faux pop song in movie history with “That Thing You Do!” from Tom Hanks’ film of the same name, losing to the ballad Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber cynically tacked on to the fraught film adaptation of Evita (1996) so that the latter could eventually EGOT. And Schlesinger absolutely, having set that precedent, deserved a nomination for “Pretend to Be Nice,” his brilliant contribution to the soundtrack of Josie and the Pussycats (2001), which is one of several films with genius original song work completely overlooked because of behind-the-scenes politics and irrelevant box office considerations, including Sparkle (1976), True Stories (1986), Velvet Goldmine (1998), Glitter (2001), Idlewild (2006), and Popstar: Never Stop Popping (2016).

Hindsight is 20/20, of course, but that fails to account for why the Academy has historically, routinely ignored and undervalued popular music genres like pop, rock, funk, R&B, and hip-hop employed in the service of cinema. How else do you explain the exclusion of Blondie’s Golden Globe-nominated, Giorgio Moroder-penned “Call Me,” from American Gigolo (1980), one of the biggest songs of its era? Or overlooking the legitimate offscreen hits “Superfly” (1972) and “Car Wash” (1976) from their respective films of the same name? Whither the ethereal, psychedelic rock homage “Beautiful Stranger” from Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999)?

Even when the Academy nominates multiple original songs from a musical film, they tend to honor the wrong one. In the case of Disney films, which so often dominated the category over the years, they frequently rewarded the more radio-friendly, commercial, and/or childish songs, dating back to the nomination of “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” over “A Dream is A Wish Your Heart Makes” from Cinderella (1950). Consider that “Chim Chim Cher-ee,” a fairly disposable, dour track from Mary Poppins (1964) took the top prize at the expense of texturally richer songs that would better weather the test of time—such as “A Spoonful of Sugar,” or, my personal choice, “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” a song later named to the American Film Institute’s 100 Films: 100 Songs list in 2004 (a list that, in so many instances throughout this program, proved vindication for a number of snubbed tracks). In 1990, “Under the Sea” claimed the prize for The Little Mermaid at the expense of “Kiss the Girl”—a more sophisticated, cinematic option—yet “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” the straightforward lion-fucking ballad from The Lion King (1994) won over the more dense “The Circle of Life,” which so perfectly soundtracks the film’s unforgettable, show-stopping opening scene…“You’ll Be In My Heart” nominated (and winning) instead of “Two Worlds” from Tarzan (1998)…

You’ll drive yourself crazy to figure it all out…and one could make the case that I did in the course of programming this.

This program looks back at three categories of Original Songs, taking into (completely subjective) consideration the quality of songs and context in which they’re featured: the all-time Best Best Original Song Winners; the Best Original Songs that were Nominated, but Did Not Win; and the Best Original Songs that, for whatever reason, including ineligibility, were not nominated (to which I’ve crafted an accompanying playlist, which excludes at least one song, Shudder to Think’s “The Ballad of Maxwell Demon,” because it is straight-up not on streaming services). This one’s got a lot of Oscars lore, Hollywood history, informed analysis, baseless speculation, and petty nitpicking. The time has come for my dreams to be heard, Curtis! They will not be pushed aside and turned…into your own…all ‘cause you won’t…listen…

There’s Gotta Be Something Wrong With Him: Antonio Banderas, Our “Latin Lover”

By the time Rudolph Valentino hit Hollywood, the culture, per film historian Gaylyn Studlar,7 was well-primed for the “Latin Lover” stereotype the actor would come to embody in his silent film stardom. At the dawn of the Jazz Age, the culture was fascinated (and abhorred) by so-called “lounge lizards,” or: “‘cake eaters,’ ‘boy flappers,’ ‘tango pirates,’ and ‘flapperoosters’ who…indulged dangerous feminine desires—on the dance floor and off.” This “stereotype of transgressive masculinity” interpreted the new social freedoms of the post-Victorian era, including dancehalls, along highly racialized lines:

“At his most dangerous he was darkly foreign, an immigrant who was ready to make his way in the New World by living off women and their restless desires…In an era in which eugenics and notions of racial purity came to the foreground in American social discourse, these men of suspicious foreign origin were thought to be an insidious threat to the nation. Their ability to sexually entice America’s women meant that the latter were weakening in their will to fulfill their primary charge: keeping the nation’s blood pure.”

There are a lot of onscreen parallels between Valentino and Antonio Banderas, his pop cultural ancestor: hailing from Italy and Spain, respectively, both actors became American sex symbols by embodying pan-ethnic, pan-racial screen personas reliant on cultural obsession with the “Latin Lover” stereotype. Reliably swarthy and brooding (and yes, transgressive), these men—sent here to seduce America’s perpetually-horny female moviegoer (who is, naturally, white)—are transformed by the force of their desires into sensitive, caring lovers by film’s end (the central paradox of the modern romance novel, first consecrated in Valentino’s era). Their ability to fulfill this crudely defined, “exotic” role in popular imagination relies on Americans’ general ignorance towards the distinctions between ethnicity and race, as well as race and national origin, content to relegate all non-English speaking peoples to a formless, fetishized Other. Both actors were accomplished dancers, a considerable weapon in their seductive arsenal—Valentino popularized the tango stateside after performing the sensual, domineering style in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), while Banderas memorably tangoed in coming-of-age ballroom dance dramedy Take the Lead (2006), a film I saw twice in theaters.

In his native Spain, where he began his film career, Banderas mastered the art of masculine pastiche, satirizing toxic masculinity in his works with Pedro Almodóvar, who discovered the young actor and turned him into an international star. Beginning with Labyrinth of Passion (1982), Banderas’ screen debut, the pair began an artistic collaboration across eight films over several decades, with Banderas embodying some of the director’s darkest (and perilously seductive) characters—including a rapist who is pushed towards unrepentant misogyny by his bullfighting instructor in Matador (1986), and a disturbed super-fan who jealously consumes the life (and bed) of his favorite gay director in Law of Desire (1987). Almodóvar elevated him to leading man status with Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989), the director’s controversial satire of machismo culture and predatory romantic narratives—his first film after breaking into the international mainstream with Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), in which a bespectacled Banderas memorably played a supporting role. Their last collaboration, Pain and Glory (2019), a semi-autobiographical film of Almodóvar’s life, cast Banderas as Salvador Mallo, the director’s avatar, earning the actor his first (and only) Academy Award nomination for Best Actor (it also won him a Goya, the Spanish Oscar, after five previous nominations).

“Is that man beautiful, or what?” Madonna, underrated cultural critic, gushes in Madonna: Truth or Dare (1991) after she’s introduced to the Spanish actor, her personal obsession, at a Madrid party thrown for her by Almodóvar. “There’s gotta be something wrong with him…no one is that perfect.”

When Banderas made the move to America—beginning with his turn as a Cuban musician in The Mambo Kings (1992), a part he learned phonetically—his subversive onscreen persona…shifted. The handsome young actor worked his way up to mainstream stardom through a number of well-received performances—including his role as Tom Hanks’ lover in Philadelphia (1993) and a memorable turn as the villainous queer-coded vampire Armand in Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994). But he broke through to leading man status—and developed the stylized onscreen persona that he’d most become associated with in American film—playing Mexican gunslinger El Mariachi in Desperado (1995), beginning a fruitful multi-film collaboration with Mexican-American director Robert Rodriguez that would see the actor repeatedly, unreservedly step into Mexican roles, kickstarting his “latin lover” era.

In his review of Desperado for Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman, sounding not unlike Madonna, wrote: “The camera loves this velvet stud as much as it did the young Clint Eastwood. With long, straight dark hair that matches his matador-cowboy outfits and a stare as hot as lava, he’s an icon of feral, strutting vengeance.”

Per Mo (my boots on the ground), in the current world of film casting, “latine” is now considered the most inclusive, non-gendered word to connote those with Latin American heritage; “latinx,” while popular in academic spaces and with young queer people, is less convenient to Spanish-speakers, given its relative irreconcilability with the language. “Latino” or “Hispanic,” which tie identities to fixed gender expressions and Spanish colonial origins, respectively, are things of the past. But back in the 90s and 2000s, those were the kinds of parts Banderas played—and audiences saw no issue with a white Spaniard taking on roles from across the Latin American diaspora, even though it’s obviously a massive point of contention these days (see: the casting of Karla Sofía Gascón, a white Spaniard, in the role of a Mexican woman in Emilia Perez (2024)). His performance in Desperado so impressed producer Steven Spielberg it earned Banderas a role as masked Mexican vigilante Zorro (his most Valentino-esque part to date) in The Mask of Zorro (1998), a throwback swashbuckling adventure film that painted the young star as the ultimate “Latino” heartthrob—a man capable of both deadly swordplay and sensuous dance, who seduces his romantic equal (Catherine Zeta-Jones, Welsh) through a sexually charged sword fight. A massive cultural touchstone, Zorro turned him into a mainstream star and forever codified his confident onscreen sexuality (and comparatively “dark” features) as an extension of his “Hispanic” heritage—and, given that so few latine stars made it in Hollywood, let alone became sex symbols, made him into something of an industry novelty (to credit him with any kind of serious diversification of Hollywood stardom would be to miss the point entirely).

The roles that followed capitalized on his exoticism—in the (admittedly) sexy, but very dubious Original Sin (2001), he’s a Cuban plantation owner who purchases a mail-order bride (Angelina Jolie); in Frida (2002), he’s Mexican social realist painter David Alfaro Siqueiros; and in And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself (2003), he plays Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, who works on a (now lost) silent film about his life with D.W. Griffith. He’d play Arab characters as well, as early as Labyrinth of Passion (1982) and as late as Black Gold (2011)—he’s even Greek, in action sequel Hitman's Wife's Bodyguard (2021). This guy is everything but Spanish! In Shrek 2 (2004), he first voiced the character he’s probably best known for today: “Puss in Boots,” a swashbuckling, dramatically-inclined cat with an accent of unknown provenance—adapted from the fairy tale of the same name—who proved to be so popular, he appeared in five subsequent Shrek-verse films, including two standalone spin-offs centered on his (very funny) character. Puss in Boots is arguably the platonic ideal of an Antonio Banderas’ character: just some silly little guy from some silly little place.

Banderas, the diversity pioneer who wasn’t, is such an odd superstar—perhaps because, as Madonna once identified, he’s clearly drawn to weird and outré roles, which feel almost at complete odds with his movie star good looks and mainstream appeal in commercial fare like Spy Kids (2001). For every dogshit film on his resume (and there’s a lot of them, like The Expendables 3 (2014), Dolittle (2020), or Uncharted (2022)) he can also claim great, unusual work in polarizing films from beloved auteurs—playing a too-horny paparazzo in Brian De Palma’s excellent Femme Fatale (2002), or “The Hermit” in Terence Malick’s Knight of Cups (2015), or the final, doomed baddie in Steven Soderbergh’s low-key good espionage action film Haywire (2011). He began his career on the stage, and frequently returns to it—earning a Tony nomination for his role (as an Italian man) in 2003 Broadway revival of Nine and headlining Spanish-language versions of A Chorus Line (2019) and Company (2021) at Teatro del Soho CaixaBank, his own theater in Malaga. So much talent, in such a handsome package. Really, he’s not at all like Rudolph Valentino, who burned bright and fast, passing at 31, forever ensuring he’d be remembered as a curio of the silent era—Banderas has lasted, aging like a fine wine since his Desperado days: our own Spanish fly, still stimulating the masses.

Living for the Knife: Plastic Surgery on Film and Television

Cosmetic surgery dates back to the Bronze Age, but the first printed use of the word “plastic” to refer to reconstructive surgery dates to German surgeon Karl von Gräfe’s book Rhinoplastik, published in 1818. Incidentally, this was the same year that English author Mary Shelley published Frankenstein, that great modern parable about a doctor willing to shape (and reshape) a man from dead, reanimated organs and grafted skin, only to be haunted by his own creation.

Over half a century later, film was invented.

We’re a long way from Frankenstein, but we’re still contending with the notion of bending the human body towards our will, reworking it into our idealized image. “We intervene in everything around us: meat, clothes, vegetables, everything: why not use scientific advances to improve our species?” Antonio Banderas’ plastic surgeon character asks of the unethical experiments he claims to be carrying out on mice—but is actually conducting on a captive human subject—in The Skin I Live In (2011), a film in which plastic surgeries are enacted as punitive, fetishistic acts of revenge. “Isn't it easier to go forward when you know you can't go back?” a “Company” staffer says to a middle-aged banker, after he’s forced to accept a costly cosmetic procedure to assume a new life (as Rock Hudson), in John Frankenheimer’s paranoia classic Seconds (1966).

Entropy is a dominant theme in depictions of plastic surgery—a necessary intervention against the realities of time on the body, which is, from adulthood, in a state of decay, preparing for death—alongside rebirth: the possibility of assuming a new life or identity through physical transformation. In Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Japanese New Wave classic The Face of Another (1966), a burn victim wears an experimental prosthetic mask that allows him to seemingly assume a new identity—but also completely alters his entire persona, as he lives out two doubled, parallel lives. In film, the plastic surgery patient occupies two personas and realities—the old self they left behind, trapped (but never fully shed) in memory, and the “new” person, perceived by the world. “I am this guy,” insists an actor (Academy Award-nominee Sebastian Stan), who, having undergone an experimental procedure to cure his neurofibromatosis, auditions for a part in a play based on his past self, which he’s now, as a normal-looking man, unqualified for, in A Different Man (2024)…even donning a cast of his old face to better achieve the condition of his old self. “It’s kind of brilliant in a way, seeing you who looks like you, but you're not yourself,” the playwright, unaware of his transformation, notes in response.

We’re currently at a moment in time in which cosmetic surgery has become increasingly normalized—even culturally expected, for people over a certain age (and for those who have the means to do it). When Chiefs’ tight end (and aspiring actor) Travis Kelce showed up at the Super Bowl this month sporting an obvious hair transplant, it was a clear marker of how far we’ve come in recognizing (and low-key normalizing) cosmetic procedures—particularly for men, often kept out of the larger cultural conversation surrounding plastic surgery. What was once seen as the desperate behavior of the shallow and insecure—and sensationalized, in the new millenium, on reality programs like The Swan (2004), which transformed “unexceptional women” into beauty queens, or Bridalplasty (2010), the most cursed brainchild of VH1 celebreality titans 51 Minds Entertainment, in which brides-to-be competed to win targeted cosmetic procedures before their big day—can now stand in the proverbial sun as an achievable form of self-improvement.

This program highlights plastic surgery’s onscreen journey from shadowy, ethically dubious procedures in seedy genres like noir—A Woman's Face (1941), The Face Behind the Mask (1941), Dark Passage (1947), and Sunset Boulevard (1950)—horror—Eyes Without a Face (1960), The Wasp Woman (1960), Rabid (1977), Faceless (1988), and Goodnight Mommy (2014)—and melodrama—A Woman’s Face (1938), Ash Wednesday (1973), and The Skin I Live In (2011)…up through the cultural normalization of cosmetic surgery in the aughts and 2010s. Television schooled the masses: televisual cultural artifacts like Nip/Tuck (2003-2010)—which burgeoning television creative Ryan Murphy based on his own experiences covering cosmetic procedures for magazines—and hit reality series Botched (2014-) painstakingly deconstructed every conceivable cosmetic procedure (and accompanying horror story), desensitizing us to the novelty of it all.

If you listen to Tik-Tok tell it, we’re in the “undetectable era” of cosmetic surgery—per Elle, “Cheeks plump, but not pillowy; skin looking taut, but not stretched”—in which the exaggerated mugs and inflated silhouettes of the past few decades have been supplanted by a desire for subtle, unclockable procedures enabled by rapid advances in cosmetic technology. America is a nation that longs to be beautiful, and uniform, even if we have to travel outside our borders to achieve it: we’re not a freak show, but a beauty pageant, showcasing American exceptionalism on an international stage. To that end, plastic surgery is right there for the ugly and unhappy to reshape their lives, pulling themselves up by their boot straps into the aesthetic reality they want to live in. Cis folks seeking gender-affirming procedures—hair plugs, testosterone therapy, facial restructuring, etc. are well within their rights, without restrictions, to seek out whatever procedure helps them feel more beautiful and free in this great, taut nation of ours. God bless America.

That’s it for February! We’ll be back next month with more original programming (and fewer original songs). In the words of Ms. Diane Warren, you don't wanna miss a thing (“I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” was nominated for Best Original Song for Armageddon (1992)), so be sure to subscribe to The Spread if you’re not already a member of our little Academy.

Though the award would have gone to Harry Warren (music) and Johnny Mercer (lyrics), it’s interesting that Louis Armstrong’s introduction of “Jeepers Creepers,” a legitimate pop hit sung to a horse (!) in Going Places (1938), lost to Bob Hope’s signature tune, “Thanks for the Memory” from The Big Broadcast of 1938, which is barely a song, at the 11th Academy Awards.

He should have redirected that moral outrage to the fact that the song won over the Andrews Sisters’ “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” the superior song, from the Abbott and Costello war comedy Buck Privates (1941), which you might recognize as the inspiration for Christina Aguilera’s “Candyman.”

Everyone likes to laugh at sixteen-time Oscar nominee (and sixteen-time Oscar loser) Diane Warren, who continues to make fake songs for fake movies in an increasingly desperate bid to win an Academy Award for Best Original Song (her latest, “The Journey” from The Six Triple Eight, seems unlikely to break the streak at this year’s ceremony)…but these jabronis aren’t even nominating the right Diane Warren songs! Other D.W. snubs include the Golden Globe-nominated “Rhythm of the Night,” performed by DeBarge for The Last Dragon (1985), and “Why Did You Do That?”, the actual best song on the Star is Born (2018) soundtrack (and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise).

While the Golden Globes, a fake awards show that traces back to 1962, frequently scoops the Academy Awards when it comes to nominating Best Original Songs—such as this year’s nomination of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ “Compress / Repress” from Challengers (2024)—the Academy Awards very rarely scoop the Golden Globes.

Guess which stupid fucking song beat “Theme from New York, New York” at the 35th Golden Globes?

I will never forgive it for winning over The Weeknd’s “Earned It,” which, to me, is one of the best pop songs of the last ten years.

Studlar wrote at length on Valentino in This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age (1996)