In Defense of Mission: Impossible II (2000)

A film so tethered to its era that it's overlooked as a masterpiece of cross-cultural action filmmaking and an example of what franchise filmmaking could be

“Well, this is not mission difficult, Mr. Hunt, it's mission impossible.”

Naturally, I was present opening night for Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part One (2023), the latest iteration of the Mission Impossible series, a popular action franchise spun off from the beloved 1960s television show of the same name. To be transparent, I’m not especially fond of franchise filmmaking (unless it features Freddy Krueger or Jason Voorhees), but I find myself a cautious ally in Last Movie Star Tom Cruise’s fight to save theatrical distribution (and practical action filmmaking), as more and more films are dumped to streaming services before they’re even given a chance to attempt to turn a profit at the theater. As a child of 90s cable television and inescapable film marketing, I find myself increasingly disoriented with the gradual erasure of a definite monoculture, when all avenues of popular media were saturated with whatever blockbuster was playing the chain movie houses. Do the children know there’s a Mission Impossible movie out right now? Do they know about the special gimbal designed to capture Tom Cruise’s acting while he plummets out of the sky? To meet this moment, I’ve been playing catch up, watching the previous Mission Impossible films (many for the first time), circling back to one unassailable, unavoidable truth: Mission: Impossible II is my favorite film in the series.

Mission: Impossible II, released four years after the mega-popular first feature film, is directed by one of my personal favorite filmmakers, John Woo, who revolutionized action cinema with his “heroic bloodshed” movies, made in Hong Kong in the late 80s/early 90s. His groundbreaking films with Chow Yun-fat like Hard-Boiled (1992), The Killer (1989), and A Better Tomorrow (1986) blend martial arts filmmaking, perfected in Hong Kong, with the Western art of gunplay; leading men are complex, emotional beings; and personal moral codes are more significant than social distinctions of law and order. Woo’s distinct style, sense of humor, and romantic approach to storytelling made him a fun — if imperfect — crossover artist into Hollywood, beginning with the Jean-Claude Van-Damme masterpiece, Hard Target (1993), in which JCVD is a Creole ex-Marine dishing out private justice in New Orleans. Broken Arrow (1996) and Face/Off (1997) — both action/comedy hybrids starring John Travolta to great effect — followed. Mission: Impossible 2 is a culmination of the filmmaker’s Hollywood period and also the point of no return: Woo never had such visibility in Hollywood as he did here, nor would he ever again. The rest of his follow-up American films faltered and eventually he returned to Chinese cinema; his last US film was Paycheck (2003) and his upcoming, fully silent film, Silent Night, will be his first American film in twenty years whenever it comes out.

Woo’s romantic action films are a refreshing rebuke of the hypermasculine posturing of mainstream Hollywood cinema, in which famous cowards like John Wayne or Steven Seagal could reinvent themselves as physical gods — if they puffed their chests up enough — and outright fascists like John Milius could creatively fantasize about the efficacy of police states, as long as those works upheld the American ideals of unassailable white patriarchal prowess. The best filmmakers to work in Hollywood action films (Howard Hawks, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Paul Verhoeven, Michael Mann, etc…) contradict or complicate their leading men, interrogating the ways in which masculinity traps and hinders men from interpersonal development, trapping them as cogs in oppressive systems of violence. Woo’s films depict male interpersonal relationships as heartfelt, emotionally complex entities that define and shape a man’s life; a man can be soft and hard, without contradiction. A Woo man cries and he certainly loves: to openly love another, in a John Woo film, is the noblest thing a man can do. After all, it’s much harder to love something than it is to hurt something. To Western eyes, Woo’s films could even read as homoerotic, such as the charged relationship between brothers (police officer) Leslie Cheung and (criminal) Ti Lung in A Better Tomorrow (1986):

Woo’s balance between the emotional stakes of his story and the thrilling beats of his action sequences actually make him (in theory) a natural fit for Cruise’s Mission Impossible series, which begins, in Brian De Palma’s 1996 film Mission: Impossible, with Ethan Hunt losing his entire IMF team in a series of brutal killings. In execution, Woo’s film drew criticism and scorn for transforming Hunt from a straightforward Cold War-era super spy to a later James Bond-style action star, beginning with an (infamous) opening rock-climbing sequence, meant to demonstrate Cruise’s striking physicality. In Mission: Impossible (1996), Ethan Hunt iconically rappels down into a highly secure room to avoid detection. In Mission: Impossible 2, he can scale a mountainside without a harness (literally: Cruise did not use a harness for the dangerous stunt, to the concern of the studio and his director).

The escalation is part of the appeal.

As a lover of maximalist cinema, I’m constantly perplexed by the late American desire to make films as streamlined and self-serious as possible, as if films with eccentricities are incapable of telling genuine stories….as if dated effects or stunts are something to be embarrassed by, rather than a charm of their respective eras. It’s true that there is a certain…goofiness…to the early 2000s that’s a trademark of the era, with its preoccupation with space aesthetics, the possibilities of the Internet, and Y2K paranoia. It’s nothing like our deeply cynical cultural moment, in which being “cringe” is the death knell for art and sincerity is treated with absolute scorn. There has been a lot of terrific writing recently about the recent flattening of popular cinema: movies are blander than ever before, both visually and emotionally. The “content farm” model of the entertainment industry has whittled all film and television down to inoffensive (or lazy) clones of everything else. Any kind of goofy flourish or artifice or moment of genuine emotional (and tellingly, romantic) expression is carefully neutralized by cutting narrative or diegetic commentary: Well, that just happened. It’s excruciating. In Mission: Impossible 2, Tom Cruise plays a game of chicken with another man while riding motorcycles. It is deeply cool. No one stops to say “Did you just play chicken with that guy on a motorcyle?!” Imagine how stupid that would be.

“In American films, every kind of movie had its own audience. The action fans only watched action movies. The comedies were only for the family. The melodrama was for whatever intellectual audience. What they liked about my movies was that they felt like I put all kinds of elements into an action film. My films had good action scenes and were very emotional — with a lot of humanity and a sense of humor.”

-John Woo to Vulture

Mission Impossible 2 is the enfant terrible of the franchise and a lasting punchline, thanks to its clear markers of early aughts excess: rock-climbing; big, beautiful locations; crazy gadgets; the aforementioned stunt bike riding; a storyline involving a deadly virus, and at the heart of it all, 38-year old, 5’7” tall Tom Cruise, America’s princess (before his complicated rise-and-fall due to his Scientologist beliefs). Everything about the film is excessive and opulent in comparison to De Palma’s prior film, a cool, stylish thriller whose only shared characteristics with its sequel film is Tom Cruise himself and a striking visual style befitting its auteur director.

Woo’s kaleidoscope vision of the IMF universe coincided with a time of unprecedented artistic conversation between East and West: with the arrival of the Hong Kong New Wave at the end of the 20th century, filmmakers out of Hong Kong were receiving new attention on the international film circuit, while American films began to liberally borrow and recycle ideas from mainstream Hong Kong cinema, particularly in regards to action filmmaking. By the end of the century, the conversation was in full swing: The Matrix (1999) was choreographed by legendary Hong Kong director and fight coordinator Yuen Woo-ping; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), also choreographed by Yuen Woo-ping and starring Woo’s muse, Chow Yun-fat, was a massive critical and commercial crossover hit; Shanghai Noon (2000) was just the latest in a string of Hollywood hits for stuntman-turned-Hong Kong box office idol-turned international superstar, Jackie Chan. In this climate of East/West pop cultural exchange, it makes sense to snap up the firebrand action filmmaker out of Guangzhou for the sequel to your massively successful spy film. Certainly in retrospect, it’s one of the coolest possible decisions that could have been made.

In this film, iconoclastic IMF agent Ethan Hunt teams up with a professional thief, Nyah, played with devastating sex appeal by Thandiwe Newton, to infiltrate the circle of a rogue IMF agent, Ambrose (Dougray Scott), her ex, who has stolen a deadly “chimera” virus (and its cure) from a bio-genetics scientist tasked with engineering it to turn a profit. Forced into a Notorious (1946)-esque double agent plot, Nyah attempts to re-seduce Ambrose while Ethan attempts to recover the virus, without raising his suspicions. This will prove especially difficult, as Nyah has since fallen in love with Ethan, with whom she has intense, romantic sex.

Along the way, Cruise, never better, moons over the girl and executes a number of impressive action set pieces, including a stunning skyscraper jump, the infamous motorcycle chicken fight (which must be seen to be believed), and a climatic beach brawl straight out of a martial arts movie. Woo borrows from a host of international cultural artifacts in pursuit of his grand, fantastic vision, including Alfred Hitchcock (a sequence at the racetrack is the film’s most obvert homage to Notorious, Hitch’s best American film), Looney Tunes, Akira Kurosawa, Jean-Pierre Melville, and (of course!) the other films of John Woo.

But Woo doesn’t simply imitate, he innovates, bringing all of those sources into the textural fabric of the film, which feels truly international (fueled by the exciting/terrifying advance of the new century) yet so distinctly Woo. The director’s signature flourishes, such as his love of scattered birds and near-poetic explosions, give the film an almost operatic gravitas reminiscent of the director’s best American experiments like Broken Arrow and Face/Off. Maybe we needed time to move forward and look back to see the true value of what we once had: I only watched the film recently for the first time, and I was struck by its relatively poor reception (which seems to boil down to the conviction that the story is “dumb,” as if all of these films aren’t relying on very well-worn archetypes and story beats, transported from television).

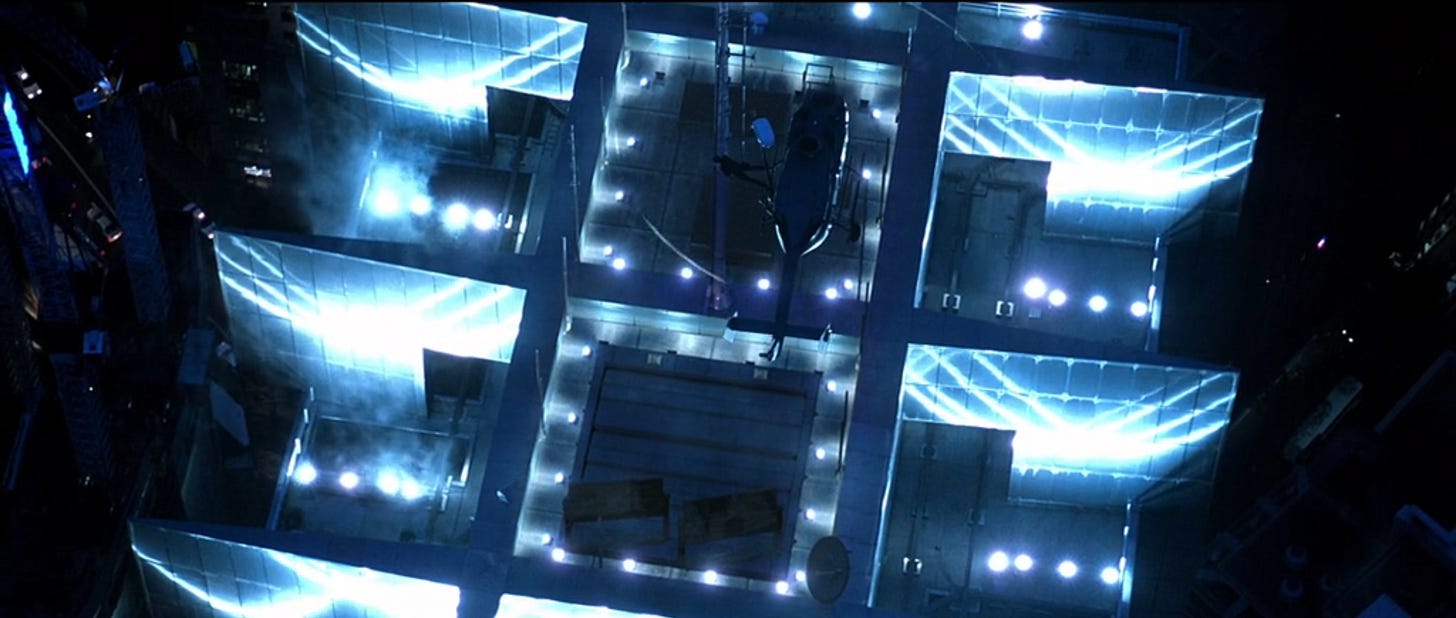

The film’s distinctiveness is its strongest asset. Watching Dead Reckoning, which I did enjoy, I was struck by how inoffensive the most recent film’s visual style is, with nothing that could visually tie it to this specific moment in time (in fact, the anachronistic waistcoats worn by both our leading man and leading lady Haley Atwell makes it feel especially stuck out of time). Everything is in service of showcasing Cruise as a moving point of interest, and while that’s certainly the appeal of the series as a whole, M:I 2 paints an unforgettable tableau of neon — evocative of the look and feel of late 90s Hong Kong — for him to move through. The futuristic bio-genetics lab, where the bulk of the action takes place, is awash in greens and blues; red laboratory lights permeate sections of the lab; refracted lights invade the frame, sometimes dotting a literal rainbow on to the filmic image. Strategic mirrors deepen the space and distort our perception. It’s (literally) all smoke and mirrors: we came to this movie to see something divorced from our world…something better than our world, extra-realized. It’s Y2K and we’re looking to the future, and Hong Kong is our ultimate visual shorthand for futuristic society. So why not evoke its multi-colored, vibrant color palette for the new millenium? “I didn't realize Hong Kong looked so beautiful at night,” Chow Yun-fat waxes poetically in A Better Tomorrow, “Such beauty can vanish in a blink.” There’s beauty here, too, in Woo’s madness: each frame drips with it. This is what we came for: to see something we can’t see in real life.

We come to this place to see Tom Cruise, sex symbol, whose carefully perfect body is the primary site of our interest and curiosity, and few can showcase a beautiful man like Woo’s careful lens. For as much as action films are stereotypically coded “guy movies,” the genre is awash with beautiful men, endearing them to female moviegoers like myself. Simply put: Ethan Hunt has never looked as sexy as he has here, with his gorgeous shag hair (the antithesis of Cruise’s ugly buzzcut in the first film), body-baring fashions, and (seemingly newfound) romantic boldness. This seems optimal, given that Cruise’s greatest appeal as an actor was in all the ways that he is different than the John Waynes and Steven Seagals of the world. He’s not just a bulk of muscle: he is a pretty man, played by an actor who would receive scrutiny his entire career for that very appeal. Consider how Tony Scott allegedly approached filming his young star for Top Gun (1986) after watching François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim, about a woman in love with two men:

“Who are you thinking for the girl in the film?”

There had been much talk about Demi Moore. Ned Tanen had just worked with her as a producer on Saint Elmo’s Fire and she was a bright young star.

“We already have the girl.” Tony [Scott] said, laughing.

“Who?”

“Tom Cruise. I told you. I am going to shoot him as if he was fucking Jeanne Moreau!”

Mission: Impossible 2 invites us to look at Cruise without shame, lingering on his face and body, offering him up to the discerning moviegoer who has paid their admission price to watch him move. Tom Cruise is not Steven Seagal, and that’s why we love watching him, even as he grows visibly older and textured before our eyes. Woo knows what he’s working with, and embraces it whole-heartedly: “My specialty is: I know how to make my actors look great,” Woo told Vulture just this year. “I know how to find the proper angle to make them look beautiful. Because I love my actors. I respect my actors. The actors in my films are everything. Every actor, I try to find a different angle or some special lighting to make them look great…even Tom Cruise — he understands it…everyone in my movies — I try to make them look great.”

Spoiler: Tom Cruise looks great in this movie.

Woo’s film was nominated for two Golden Raspberry Awards, including Worst Remake or Sequel and Worst Supporting Actress for Thandiwe Newton, the latter of which is a particularly egregious offense considering that her sly, sexy performance as a Millenium Ingrid Bergman is one of highlights of the film. Those awards have always been meaningless (Newton’s nomination reminds me of Shelley Duvall’s singled out nomination for Worst Actress for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining), but they help paint a cultural perception of the film as especially bad and shape the narrative of these things for years to come. Looking back on the film in the context of the seven (and counting) sequel films, Mission: Impossible 2 feels especially noteworthy because it’s so incongruous with its sister films, which have amped up the impressive stunt work (thanks to the model established by Woo), but have failed to replicate its unique visual style and full-throated embrace of the heroic bloodshed formula, which finds extreme emotional weight in the ways in which man makes sacrifices to survive a violent world.

A film from the year 2000 should be a snapshot of the cultural forces shaping that era, and I don’t think that quality in it of itself neutralizes a film’s staying power. Despite the popular narrative that it represents some kind of creative failure, Woo’s film maintains a cult following with a niche group of genre film fans. It’s a John Woo film starring Tom Cruise! If it’s dated or especially tethered to its era, that’s only in the best interest of the film’s legacy, as it is a real standout in an increasingly self-serious action franchise (based off a television show that looked like this). If anything, it’s an example of what franchise filmmaking could engender: deeply bold visions from individual artists leaving their creative stamp on a shared formula. In an era of remakes and endless franchise filmmaking, in which everything is designed as a cog in some grand, bland totalizing universe, being the maligned freak of a film series is actually deeply refreshing and cool.

“Let's get lost,” Cruise muses in the film’s final moments, which may as well serve as the film’s epitaph, buried as it has been in the years since, particularly after the (successful) franchise recalibration with JJ Abrams’ Mission Impossible III, practically designed in a lab to please everyone, followed by the death-defying thrills of the Christopher McQuarrie films (4-8). If MI:2 fails to fit, that only speaks to the ways it’s unlike any of its counterparts. If the film is an example of a franchise losing its way, may we all make such sublime mistakes.

Mission: Impossible II is currently streaming on Paramount Plus. Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning- Part One is in theaters.

“When people came to watch my movies, they didn’t know if they should laugh, cry, or be angry. But I don’t regret it, because I feel, as a filmmaker, you’ve got a duty to serve the truth inside your heart. No matter if it’s a comedy, action, or a love story, I’ve got to bring my true feelings into the film. I don’t want to hide and be happy. If I’m not happy, I don’t want to do something to try to please anybody.” -John Woo