Well, welcome to January streaming.

New York is so very cold, Los Angeles has burned, and David Lynch is dead.

We’ve made plans and resolutions, withheld and abstained, judged and reprimanded, curtailed and castigated…and each day feels harder, grayer, longer, and emptier than the one before it. I have everything and nothing to say, and each time I sit down to write, I feel like I’ve forgotten how to do it. The brain is just an organ and mine must be atrophying. This month, I come only with absolution for the lazy and uninspired, preaching the gospel of taking it easy against the backdrop of an unfeeling current moment. Our programming this month…is a different story. January is a cold, dark, putrid month—made beautiful only by the artificial glow of the silver screen. Why do anything else, when the movies are right there waiting for you, begging to be watched?

This month, it’s (not quite) out with the old and in with the new, as we take one last look at 2024 and pick through some discarded cinematic curios that have rusted over with time. Despite the melancholy, we’ve got a supersized block of programming, including retrospectives on the two sexy, wisecrackin’ co-stars of The More the Merrier (1943): both (incredibly underrated) screen icons who pivoted to Westerns at the top of their game before leaving it behind entirely. Elsewhere, we’re pumping in enough serotonin to carry you through these bitter weeks. Don't you know, pump it up? You’ve got to pump it up…

Pump it Up: Bulking Up (and Getting Shredded) on Film

“Let's say you train your biceps: blood is rushing into your muscles and that's what we call The Pump,” a 28-year old Arnold Schwarzenegger explains in voiceover in Pumping Iron (1977), the cult sports documentary (and lodestar for this program) that put him and bodybuilding—in that order—on the map. “Your muscles get a really tight feeling, like your skin is going to explode any minute, and it's really tight—it's like somebody blowing air into it, into your muscle. It just blows up, and it feels really different. It feels fantastic.”

For the more-determined among us, January means a return to the gym: a resolve to retrain our bodies after the indulgences of the holiday season into the lean, mean, and efficient machines we long to be. For those addicted to It—the Pump, the zone, the itch, the buzz, the dopamine hit, the drive, the burn, the high—there’s nothing quite like the pull towards strenuous physical fitness, and the call to work harder, better, faster, stronger, which is what this program is all about. Getting jacked is inherently American, to hear our great leaders tell it. On April 10, 1899— five years after Edison released a series of films of strongman Eugen Sandow flexing for the camera—President Theodore Roosevelt, who turned to boxing at a young age to overcome a sickly childhood constitution, delivered “The Strenuous Life” speech in Chicago, waxing on the patriotic virtues of an active lifestyle:

“If we stand idly by, if we seek merely swollen, slothful ease and ignoble peace, if we shrink from the hard contests where men must win at hazard of their lives and at the risk of all they hold dear, then the bolder and stronger peoples will pass us by, and will win for themselves the domination of the world…let us shrink from no strife, moral or physical, within or without the nation, provided we are certain that the strife is justified, for it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness.”

In Pain & Gain (2013), Michael Bay’s dark comedy about a real-life gang of Miami bodybuilders who descend into a life of crime, Mark Wahlberg puts it another way: “When it started, America was just a handful of scrawny colonies. Now, it's the most buff, pumped-up country on the planet: that's pretty rad.”

Hollywood’s preoccupation with enviable, fit bodies really reaches all the way back to Douglas Fairbanks—that great superstar of the silent era who became the physical embodiment of All-American values and virile masculinity. But American film’s love affair with cut, bulging bodies really took off with the explosion of physical fitness culture, largely attributed to the burgeoning scene at Muscle Beach, an outdoor gym off the Santa Monica Pier built in the 1930s under the Works Progress Administration. There, jacked fitness figureheads like Vic Tanny, the father of the modern, now-ubiquitous “fitness club”; Jack LaLanne, who hosted the first nationally syndicated television show dedicated to fitness; and Joe Gold, founder of Gold’s Gym, worked out and built followings, epitomizing California Beach Body Culture. Tanny was even parodied in Muscle Beach Party (1964), the gloriously corny second “Beach Party” film—in which teen idols Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello fight an outrageous bodybuilding coach (Don Rickles) over use of the beach.

One of Joe Gold’s patrons, Arnold Schwarzenegger, began training for bodybuilding competitions at Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach, and while Pumping Iron (1977) made him a famous name, he’d change the look of male action film stardom forever when he crossed over into leading roles with Conan the Barbarian (1982), John Milius’ outrageously entertaining, unrepentantly violent swords-and-sandals schlock fest, which took great care to bare and showcase Arnold’s super-bulky body. Schwarzenegger’s eventual rival, Sylvester Stallone—already a fitness icon thanks to Rocky (1976)—really began to bulk up in the 1980s, culminating in his ubermensch physique in both Rocky III (1982)—where he was shredded to 166 pounds and 2.8% body fat—and Rocky IV (1985), the latter of which incorporates one of the all-time great training montages in film (it just…keeps…going…), a major inspiration for this program. Around the same time, professional wrestling (and Hulk Hogan) hit the mainstream, thanks to the machinations of the villainous genius Vince MacMahon, who successfully cross-promoted the first-ever WrestleMania (1985) with hip new music network MTV, programming a buzzy wrestling special with wrestler Wendi Richter and fan Cyndi Lauper, The Brawl to End It All, that brought in a young crowd (and, incidentally, turned a spotlight on women’s wrestling).

Suddenly, everywhere you looked, big, hunking bodies were de rigueur, (secretly) fueled by the normalized use of anabolic steroids, which turned strongmen into beasts, skewing our notion of what the human body could look like (and what it was capable of). America really was becoming the most buff, pumped-up country on the planet—and the existential threat posed by the similarly cut bodies of the USSR, courtesy of a formal Soviet sporting culture, was one we were willing to try and crush, repeatedly, at international sporting competitions and in virtually all of our popular media. And when women got into the heavy fitness game as well, it drove paranoia about the collapse of gender distinctions—a tension captured in cult sequel Pumping Iron II: The Women (1985), in which badass powerlifter Bev Francis’ uber-bulked-up physique raises accusations that she’s not “feminine” enough, capturing female bodybuilding at an ideological crossroads (and presaging our own current moral panic about women’s sports).

We’ve never really slowed down since, not really, even after we (allegedly) got rid of the steroids, and this program honors the films that exemplify our “no pain, no gain”1 culture and shape our cultural understanding of fitness. Here you’ll find a collection of (fiction and nonfiction) combat and contact sports movies and television shows, from wrestling to martial arts to boxing, as well as audiovisual love letters to bodybuilding and power training. Additionally, Real Hollywood Movies that continually define (and redefine) male physique, like Fight Club (1999)—the film that launched a million male eating disorders thanks to Brad Pitt’s lean, enviable build, still the preoccupation of fitness websites and forums even 20 years after its release. Or the sea of bare washboard abs in Zack Snyder’s 300 (2006), chiseled to a fine point by celebrity trainer Mark Twight, who later worked with Henry Cavill to develop his equally unattainable body for Man of Steel (2013), which completely redefined the look of male movie stars in the 2010s (uber-jacked, and completely de-sexualized). Finally: selections from beyond our borders, like the harrowing Peking opera training that molded the unbreakable body of Jackie Chan, and the Japanese nationalists who saw cut bodies as an exemplification of a superior culture. (It’s almost like preoccupation with physical fitness is a manifestation of nationalist ideology no matter where it takes root!). The works selected for this program don’t just display bulked-up bodies: they capture them in motion, highlighting the arduous training and discipline that goes into sculpting a human body into a living work of art (and a well-oiled machine). And, because one program is not enough, we’ve added a bonus circuit—that’s two pump it up-themed programs for the price of one! Maybe they will inspire you to hit the gym…or maybe you’ll wind up watching really fit people pull a 1.5 ton boat up a ramp while eating ice cream from your couch. No judgement this month!

Celluloid Heroes Never Feel Any Pain: Jean Arthur on Film

Cinema history is littered with glamorous women, whose otherworldly beauty, severity, and brooding allure make them feel like unattainable goddesses, perched high atop the heavens. They are helped in and out of carriages and cars, carried across ballrooms, and perched on divans, flanked by butlers and festooned with jewelry, liable to seduce a room with a simple gesture; simpering, sweet swans epitomizing the fairer sex.

Jean Arthur was not one of those women.

“Look, when I came here, my eyes were big blue question marks,” Arthur snarks in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), in which she plays a secretarial aide forced to babysit a stooge baby senator at the behest of the political bosses intent on pulling his strings. “Now, they're big green dollar marks.” She’s a tough, cynical, smart woman, who spends the first half of the film mocking her charge’s naiveté in a cutthroat, corrupt Washington D.C., only to fall for the man’s guileless nature, coaching him, by film’s end, with the procedural knowledge to take on the bigwigs. That’s the classic allure of Jean Arthur: she may act tough, but ultimately, she’s real solid stock, the kind of salt-of-the-earth people they used to write folk songs about. She’s an honest working girl: a scowling smart aleck capable of melting down into sweet sincerity if so moved. She’s never the richest or prettiest girl in the room, but she’s always the most interesting, continually forced to land on her feet, even when the rug is pulled out from under her. In that sense, she’s the most relatable of the great screen idols: she feels—particularly given the painfully limited roles for actresses back in the day—incredibly, strikingly modern. I don’t think she gets enough credit for breaking the mold as she did. She’s just one of the girls!

Arriving in Hollywood during the silent era, Arthur spent years toiling in thankless bit parts at her first studio, Paramount, lost in a town that seemingly had no place for a gal like her, even after successfully crossing over into talkies. After a spell on Broadway, Arthur got a new contract—and a second chance—at Columbia, where she finally blossomed in the “screwball comedies” that the studio became known for. Her time in silent film trained her to be incredibly expressive onscreen, and she had this great knack for selling long, extended bits without having to say a word—like tying a little blindfold on her piggy bank before smashing it to pieces in Easy Living—communicating so much with just her face. She broke through to mainstream stardom with her gangbusters performance in John Ford’s The Whole Town’s Talking (1935), playing a rare love interest for Edward G. Robinson: streetwise and no-nonsense, she struts through the film like a real-life Bugs Bunny in Girl Mode, mugging, scheming and cracking-wise like one of the guys (but still with a girlish, coquettish energy). It’s no surprise she’d go on to embody the “Hawksian woman,” so-named for the female characters that appeared in the films of “man’s man” director Howard Hawks: a woman who—while not expressly feminist—countered stereotypical depictions of “the weaker sex.” The Hawksian woman is smart, beautiful, and ballsy, but above all else, she stands by her man, even when the going gets tough. “I’m not trying to tie you down,” she coos, in that casually devastating way of hers, to Cary Grant in Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings (1939), a stirring, sparkling dramedy about a woman who falls for a daring airmail pilot in the treacherous Andes Mountains. “I don’t want to plan, I don’t want to look ahead, I don’t want you to change anything…anything you do is alright with me.”

Her forte was comedies—playing a plucky labor agitator in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); trying to hand-return a fur coat that lands on her head in Easy Living (1937), penned by Comedy Svengali Preston Sturges; and secretly shacking up with Ronald Colman and Cary Grant in George Stevens’ The Talk of the Town (1942). But Arthur’s true maestro was Frank Capra, with whom she’d appear in three pictures that skillfully fused comedy and drama, all of them stone-cold classics: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), with Gary Cooper, and You Can't Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), with Jimmy Stewart (with whom she had particularly devastating onscreen chemistry). (Italian immigrant) Capra’s idealistic conception of America was a place where ordinary, hard-working people were capable of great, impossible things, if only the people at the top would give them a shot. If you’ve seen It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), his best-known film, you know exactly what I’m talking about—Arthur, the exact kind of extraordinary ordinary person he adored, was originally set to co-star with Stewart again, but was replaced by Donna Reed: the nerves that would plagued her her whole life had, by that point, consumed her whole.

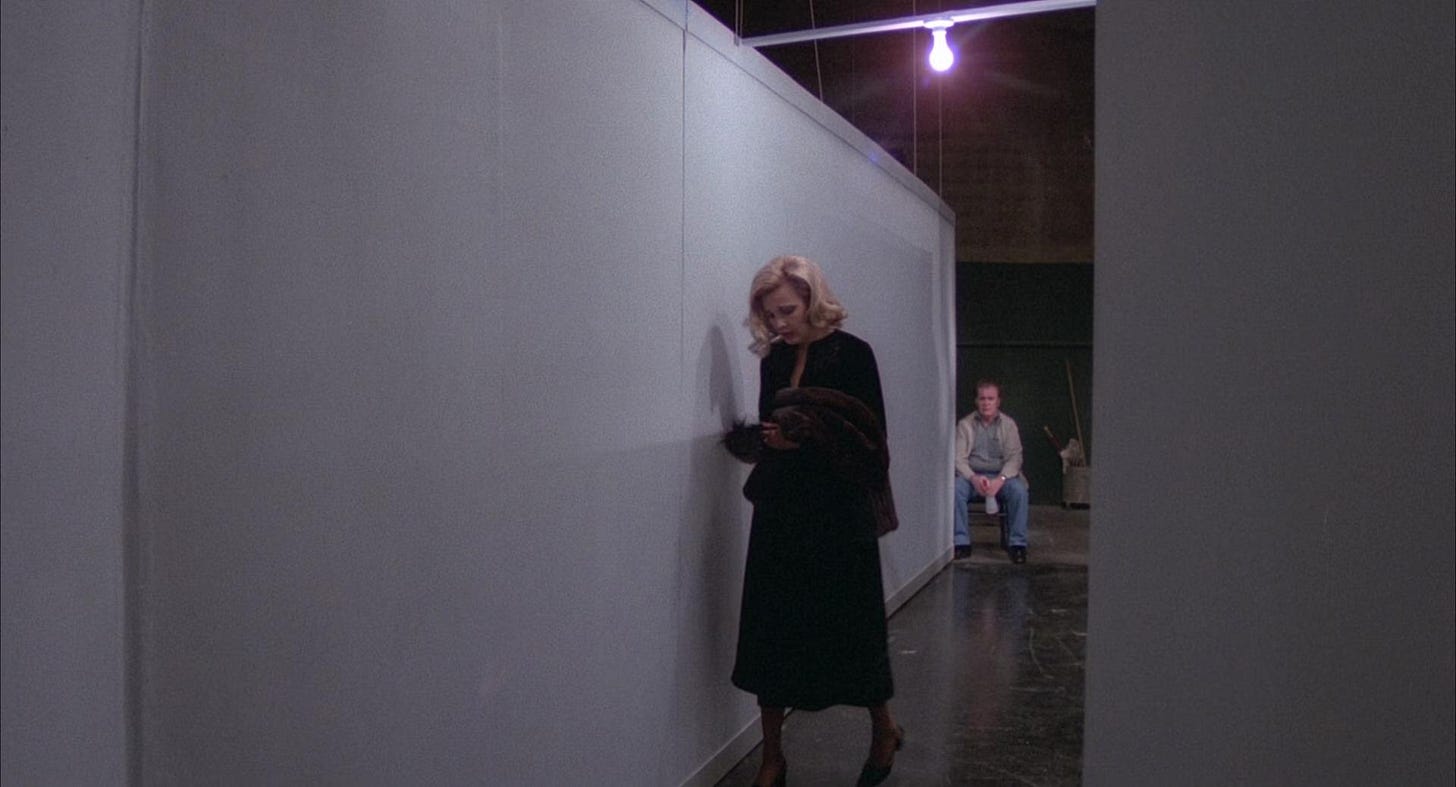

There’s very little we actually know about Jean Arthur, beyond what she committed to film. Fiercely private and loathe to comment on herself (as legend has it, she once said she’d rather slit her throat than give an interview), she retired from Hollywood pretty much as soon as her contract with Columbia was up in the 1940s, returning only for Billy Wilder’s delightful A Foreign Affair (1948) and George Stevens’ Western classic Shane (1953). Her reticent nature offscreen stemmed from being painfully shy, and eventually, she just couldn’t hack it anymore—she dropped out of the original stage production of Born Yesterday, clearing the way for Judy Holliday to become a new star, starting the cycle anew. Subsequent attempts to return to the stage were equally unsuccessful, and a brief television show bearing her name lasted just one season. Watching her on screen, you’d never know that such a vibrant, confident woman could be the construction of someone so plagued with self-doubt and insecurity—something that is, to me, incredibly inspiring. Despite her timidity, she became one of the signature leading ladies of her time, leaving behind an impressive cinematic legacy and successfully crossing over from the silent era thanks to that distinctive voice often described as “husky.” Slightly lisped and high-pitched, I find it girlish, a sonic precursor to the “baby voice” some of us gals just can’t shake off. To me, she sounds a lot like my late aunt Pat: just a normal American woman. But man, what a woman!

One Right Note: The Lasting Allure of Joel McCrea

What if—instead of Gary Cooper or John Wayne—there was a third, and Better, Man? Well, that’s sort of Joel McCrea, the dishy, underrated leading man-turned-rancher whose offscreen humility, quiet personal life, and early retirement from the movies make him something of an undersung figure in the great tapestry of Classic Hollywood lore (and a total anomaly in the fast-paced, scandal-ridden industry of yore).

Few were as immune to the perils and pitfalls of Hollywood as McCrea—a dreamy, lanky leading man known for his deadpan delivery and mastery of multiple genres, but whose acting career, terrific as it was, forever played second fiddle to his real love: ranching. The grandson of a stagecoach driver, McCrea got his start in Hollywood as a horse wrangler in old Western serials, and he began buying up land as early as the 1930s, eventually consolidating it into a 3,000-acre ranch in Thousand Oaks, CA, where he lived after (mostly) retiring from Hollywood by the late 1950s. He began his career as shameless eye candy in a number of deliciously sleazy pre-Code RKO pictures, including The Most Dangerous Game (1932), a blueprint for the modern horror film; The Silver Cord (1933), an audacious interrogation of the incestuous dynamics of overreaching “boy moms”; and Birds of Paradise (1932)—a steamy island picture that drew controversy for its depiction of “miscegenation” between leads wearing very little clothing, with McCrea as openly on display as his co-star, Dolores Del Rio.

Towering over six feet, McCrea was a hunky favorite of the top leading ladies of the era—particularly Miriam Hopkins, Barbara Stanwyck, and Constance Bennett—both for his offscreen gentlemanly nature and onscreen tall stature, which forced his screen partners to look up, offering a flattering angle of their necks. Even in his earliest pictures, he has an undeniable everyman appeal and an aptitude for onscreen lovemaking that suggests the offscreen life of someone far more promiscuous (Lord knows Hopkins tried hard to get with him when the cameras went down). After the implementation of the Hays Code limited the onscreen depiction of sex, McCrea’s rugged sensuality kept it steamy, putting over a lot of sexless “sex scenes.” He met his future wife, Frances Dee, on the set of the Silver Horde (1930), and—contrary to Hollywood convention—the pair stayed blissfully married from 1933 until his own death in 1990 (on the 57th anniversary of their wedding).

McCrea took an understated approach to acting, which served him particularly well in screwball comedies, as his taciturn, strait-laced persona helped “sell” the outrageous situations he found himself in onscreen, much in the way Buster Keaton would straight-face a scene while the scenery fell down around him. In the early 1940s, McCrea became the mouthpiece for wunderkind writer/director Preston Sturges, then on a seismic run of hit comedy films, beginning with Sullivan’s Travels (1941), his most personal work, now considered to be one of the greatest American comedies of all time. McCrea plays a successful, privileged Hollywood director who longs to helm O Brother, Where Art Thou?, a rousing social drama that will help him move away from the irreverent comedies he’s become known for and into stronger stuff. Desperate to learn how the other half lives, he hits the rails, playacting poverty, learning the hard way that comedy and tragedy are never that far apart. I don’t think anyone else of that era could have walked the film’s fine tonal line, which is just so strikingly modern (and speaks to Sturges’ relative creative freedom in the highly-regimented studio system).

McCrea would make just one more truly great film with Sturges—The Palm Beach Story 1942), truly one of the funniest movies ever made—and one more really bad one—The Great Moment (1944), about the discovery of ether as anesthesia for dental surgery, which sounds like a 30 Rock joke, and effectively killed the Sturges’ career, ending the pair’s association. McCrea smoldered opposite Jean Arthur in the utterly delightful The More the Merrier (1944), but after The Virginian (1946)—which later inspired a hit television series of the same name—he pivoted almost exclusively to Westerns, and when Westerns moved to television, he retired all together, content to live out his days working his ranch. Still, several of those Westerns are considered bonafide classics of the genre, including Jacques Tourneur’s Wichita (1955), in which he plays Wyatt Earp, and Sam Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country (1962). One of the films he made with Jacques Tourneur during this period, Stars in My Crown (1950) was particularly notable for its egalitarian sentiment and standout performance from groundbreaking Afro-Puerto Rican actor Juano Hernández, who plays a freed slave targeted by the KKK for refusing to sell his land. Despite a few outliers, McCrea’s career was pretty much moot by the 1960s.

McCrea was never nominated for any big awards or fetishized by international cinephiles, despite appearing in almost a hundred films dating all the way back to the silent era. People figure he never earned superstardom because he never really…sought it out: he was certainly as talented—if not more so—than either Cooper or Wayne. If he fails to get the name recognition he deserves nowadays, maybe it’s because he made acting look too easy: his performances are deceptively simple, deeply modern, and unpretentious in execution. He summed it up the best when he once remarked, “People say I’m a one-note actor, but the way I figure it, those other guys are just looking for that one right note.”

Oh, That’s Not—Films that Have “Aged Poorly”

In August of last year, the New York Times profiled former NFL player Michael Oher amidst his ongoing lawsuit against the Tuohys, a white Tennessee family best remembered as the couple played by Tim McGraw and Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side (2009), an early Obama-era, post-racial sports drama that earned the latter an Academy Award. In the film, Bullock plays a tough “tiger mom” to her adoptive son, Oher, a working-class black kid stuck in the foster care system, who she puts up in her home. In reality, the couple, who have since made a pretty penny on the lecture circuit as the “real-life” inspiration for the film, never adopted Oher, but they did lock him in a cartoonishly sketchy conservatorship, through which they controlled all his funds and life decisions for 20 years, including through the entirety of his professional football career and The Blind Side fame. The Tuohys were close family friends with Michael Lewis, the author of the book that later became the massive hit film, and the couple subsequently received a favorable, outsized role in Oher’s life story, which was even further distorted on the way to the big screen. As the NYT profile points out, Oher, played by Quinton Aaron, barely speaks in the film version, content to passively watch the events of his own life from the sidelines; a depiction that—in Oher’s opinion—perpetuated the idea that he was stupid, negatively impacting his professional career. It’s a depressing, if unsurprising, coda to a story pegged from release as racist: a classic white savior narrative by which a person of color becomes a side character in their own life story. But knowing the full extent of the Tuohys’ exploitation of Oher—beyond simply co-opting his accomplishments as their own—really does illustrate what a vile little film it truly is. Ham-fisted on arrival, it has only curdled in the years since.

What do we mean when we say a film “Aged Poorly?” It’s easy to point to films like Birth of a Nation (1915), Song of the South (1946), or the still-unreleased The Day the Clown Cried (1972)—we’re getting it this year, folks!—obvious Bad Ideas that came out the gate as Bad Ideas…but where’s the fun in a program like that? I think we can dig a little deeper and dredge up the cinematic curios that—for whatever reason—everyone would like to forget happened. (It just feels right for January, a month known as a dumping ground for movies doomed to fail and be forgotten). What happens, for example, when you make a biopic about an international human rights icon2 who is later accused of abetting ethnic cleansing? Failed hagiography, cringeworthy propaganda, doomed premises, and movies twisted and reshaped with the influence of real-life events…don’t you just love the complex, ever-shifting intersection of life and art?? We’ve got it all: the Ridley Scott war film that lionized a convicted pedophile and cast Obi-Wan Kenobi in the role, the mean-spirited Gwyneth Paltrow comedy that gave her “fat” body double an eating disorder, Mel Gibson’s conspiracy theory movie (from 1997…), the blackface film Ronald Reagan screened at Camp David, Woody Allen’s If I Did It (it’s not Manhattan),3 and the movie where Rambo literally had to hand it—and the “it” was explosives—to al-Qaeda.4 Remember On the Basis of Sex (2018)? Can you name the movie that first brought Ted Danson and Whoopi Goldberg together, culminating in a near-career ending blackface scandal at a Friars Club roast?5 How can you tell if you’re watching the crow’s nest movie from Inglourious Basterds (about some sort of “lone survivor,”6 if you will) without a hint of irony? And do you think Ron Howard—when he tucks himself in bed at night, far from our prying eyes—regrets elevating a hack hillbilly to the second highest office in the land?7 Finally, with the recent passing of Olivia Hussey, we’ve got plenty of heat for the real-life predator who forced her to appear naked—at age 16—in a goddamn Shakespeare adaptation, and the creeps that sexualized Brooke Shields and Natalie Portman when they were still underage…and if you think I’ve forgotten about Bryan Singer’s crimes— including the lawsuit he incurred from the families of underage boys on his sophomore film—just because he’s currently hiding out in Israel, I have not!

I’d never advise against watching a movie (unless, of course, it’s Gigli, not included in this program), so let’s take a second, more critical look at these!

Favorite First Watches of 2024

As we look forward into the New Year, I look back at my favorite first watches of 2024: 50 (new-to-me) watches, from glaring, still-relevant blind spots—like For a Fistful of Dollars (1964), The Battle of Algiers (1966), and The Long Goodbye (1973)—to instant all-time favorites—like Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), True Stories (1986), and Mississippi Masala (1991)—to a surprising number of sport-centric classics—like This Sporting Life (1963), about rugby; Bull Durham (1988), about baseball; and Love & Basketball (2000)—to two of the late Gena Rowlands’ most beautiful performances, in Opening Night (1977) and A Woman Under the Influence (1974). The past has so much to teach us about the present, so here’s to the cinematic discoveries that await us in the year ahead. If you’re interested in my take on The Best Films of 2024, you can check out my ballot over at Film Comment, which, in the interest of full transparency, I submitted before I’d seen Nickel Boys, a beautiful film that I probably would have included in the list.

That’s it for January! It’s the worst time of the year and it’s hitting especially hard this time around, so try to be kind to yourself and others…except for the fascists taking office on Monday, of course. To them I say a long and hearty: fix your hearts or fucking die. Until next time, we're together in dreams, in dreams…

Fun fact you (maybe) didn’t know: “No pain, no gain!” was popularized by Jane Fonda in her groundbreaking workout tapes: legitimately, and without hyperbole, one of the most cultural significant products of the 1980s and galvanizing to the sale of home video systems.

Luc Besson’s The Lady (2011), which stars Michelle Yeoh as (since disgraced) Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, which the director has since admitted he regrets making.

(It’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, which is, in my humble opinion, better than Manhattan).

Rambo III (1988), which, contrary to popular belief, does not end with a title card thanking “the brave Mujahideen fighters of Afghanistan,” a popular urban legend, though the film does basically express that exact sentiment.

Made in America (1993), a film in which the pair plays (sperm donor) father and daughter.

Peter Berg’s Lone Survivor (2013).

Here’s another wonderful tribute to the great Jean Arthur!

https://music.apple.com/us/album/jean-arthur/1700578270?i=1700578614