“‘Give me your hungry, your tired, your poor, I’ll piss on ‘em’: that’s what the Statue of Bigotry says,” Lou Reed sang on his album New York, from 1989. “Your poor huddled masses, let’s club ‘em to death, and get it over with…”

Welcome to June streaming.

Lou’s scathing words have been rattling around my brain a lot this month, as I struggle to keep it cool and light for The Spread while alternating between rage and despair. Here in New York, in 2025, his “Statue of Bigotry” looms large on the dirty boulevard: at 26 Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan, the gestapo forces of ICE are arresting immigrants who show up for routine immigration appointments, including mandated appearances, citizenship applications, and asylum hearings—effectively punishing them for taking the steps towards a legal path to citizenship. Just yesterday, mayoral candidate and city comptroller Brad Lander was arrested for trying to escort a man out of the building during one such attempted detainment. Other politicians attempting to visit the federal building to investigate reports of poor conditions in holdings cells have been barred by ICE, an organization that is now detaining migrants at such a scale that they cannot adequately house them all: these poor masses, separated from their families, huddle in cramped cells without showers or changes of clothes for days. And it’s only the start of their imprisonment: a lot of powerful people still have a lot of blood money to make off their backs first. How can one country contain so much collective agony?

I keep coming back to the embittered poetry of New York filtering through my headphones: “Americans don't care for much of anything…with human life not worth more than infected yeast.” But “this is no time for inner searchings: the future is at hand.”

I just keep my eyes open and keep on looking: backwards, then forwards.

For this month’s main program, we’re looking at stories of incarceration, and the psychological toll it takes on the people caught in cages, traps, chains, and camps. It’s a heavy program for an incendiary month: the start of summer, June tends to kick off a wave of political action and violence, as warmer temperatures boil into fervor in the streets. Juneteenth is a celebration, but it also recognizes a miscarriage of justice perpetrated by white power structures: the arrival of Union troops in Galveston, Texas, delivering news of the Emancipation Proclamation, two whole years after slavery was abolished. The fight for freedom would last far longer.

There’s some lighter fare as well. Elsewhere, a helping of Pride-friendly programming, including a tribute to “Good Judys,” the return of the queer cinema canon, and a real (and appropriately messy) bi icon for our actor showcase; a man who helpfully reminds us that “if you’re going to stay cool, you’ve got to wail, you’ve got to put something down, you’ve got to make some jive — don’t you know what I’m talking about?”

Let’s get into it.

If I Had the Wings of an Angel, Over these Prison Walls I’d Fly: Incarceration on Film and Television

On a recent visit to the New York Tenement Museum, our knowledgeable docent handed us a document illustrating the impact of the Immigration Act of 1924—also known as the Johnson–Reed Act—which capped immigration by country and unilaterally barred immigration from Asian nations: an attempt to preserve the homogeneity of the United States in the wake of mass immigration at the end of the 19th century. The point, he argued, was to remember how recent such formal restrictions on immigration actually were: the act authorized the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol, the first border patrol service in the nation’s history. The United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the law enforcement agency tasked with enforcing immigration, was only formed in 2002, in the wake of 9/11: it has been strengthened and emboldened across four presidential administrations, regardless of the ruling party, in the years since. That failure to curtail its amassing power is now proving to be disastrous, as the organization acts entirely of its own accord, without oversight or due process, detaining migrants from behind the safety of masks and civilian clothing. Recently, private prisons have stepped up to fulfill the agency’s ambitious designs: NPR claims, through data from TRAC, that nearly 90% of those within ICE custody are being held in facilities run by for-profit companies, predominantly in Southern states. This arrangement, effectively, puts a value on the life of every human being held in such a facility.

“Never in our 42-year company history have we had so much activity and demand for our services as we are seeing right now,” Damon Hininger, the surprisingly shameless CEO of CoreCivic, a private prison company, told enthusiastic shareholders on an earnings call last month, per the Associated Press.

The company, along with GEO Group (whose former lobbyist, Pam Bondi, is now the Attorney General), is one of several players in the big business of private prisons recently tapped by ICE to reopen old, idle facilities to house detained immigrant populations through no-bid, multi-million dollar “letter contracts,” hastily reworking old agreements to meet massive demand as the Trump Administration ramps up deportations—and mass migrant detention. In Leavenworth, Kansas, a formerly vacant facility in the longstanding, historically notorious prison town, shuttered in 2021, is reopening through a cushy, $4.2 million-generating deal for CoreCivic. Previously closed facilities are also reopening in Newark and Dilley, Texas through similar contract deals. Last month, detainees at a facility in Texas operated by private prison company Management and Training Corporation formed an “SOS” message with their bodies to protest the deplorable conditions inside the facility, typical of such sites, where extensive violence, unfettered use of solitary confinement, overcrowding, sexual abuse, and lack of food and proper medical care are commonplace. Because ICE so rarely fails to renew contracts, there is no incentive to reform or curtail abuse or violence within the private prisons it employs, and because these prisons are run for profit, they are incentivized to cut costs wherever possible, contributing to subpar conditions. This systemic neglect and violence is, of course, by design: make the fear of incarceration so significant that it encourages self-deportation (itself an incredibly dangerous process).

In 2019, The Atlantic reported on the punitive use of solitary confinement inside immigration detention centers under the Obama and Trump administrations over infractions like “menstruating on a prison uniform, kissing another detainee, identifying as gay,” as well as general mental health issues. Prolonged use of solitary confinement—which, per the United Nations, constitutes a form of torture—was used in dozens of instances, according to internal records obtained by several news organizations, including at least one incident involving a man held for more than 780 days: that’s over two years of living in a single, confined cell, without human contact. We cannot possibly understand the profound agony created by such extended confinement, though we do know its impact on the human body: heart disease, anxiety, depression, psychosis, increased risk of suicide, substance abuse, and self-mutilation. In other words, it erodes the mind and destroys the body; it crushes the will to survive. After Kalief Browder was held in solitary confinement for 800 days while serving three years at Rikers Island over a spurious claim that he stole a backpack, the Bronx teenager was never able to overcome the mental strain of the prolonged isolation endured while he was still underage, even after he was freed upon dismissal of his case. “Being home is way better than being in jail,” he told the New Yorker in 2014. “But in my mind right now I feel like I’m still in jail, because I’m still feeling the side effects from what happened in there.” Tragically, Browder died by suicide in 2015, a true victim of the carceral state and a Kafkaesque judicial system—a galvanizing incident in the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s.1

Browder’s story is one of several real tales of incarceration captured in this month’s program, which looks at the cinematic depiction of imprisonment, fictional or otherwise. The modern-day police state historically stems from slave patrols, which terrorized freed and enslaved Black Americans well after the formal abolition of slavery. In honor of Juneteenth—which commemorates the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas—and in recognition of the shameful expansion of the carceral state in recent months under ICE, it felt appropriate to try and put together a program that tackles the theme of imprisonment directly. I’ve tried to curate a diverse set of works that honestly engage with the nature of incarceration, rather than sensationalize life behind bars. These include documentaries on the carceral state; prisoner-of-war films; stories of political prisoners and uprisings; dramas about juvenile detention like the British borstal system (and the Young Offender Institution system that replaced it); chain gang movies; conceptual films like Woman of the Dunes (1964), Cube (1997), and The Platform (2019); and films with characters whose lives have been radically transformed by time inside like Thief (1981) and Scarecrow (1973). Prison—an inherently evil, worthless institution—aims to strip the individual of their personhood as a means of controlling them, achieved through dehumanizing, indiscriminate violence. It’s my hope that putting these films in conversation with each other will—rather than feel exploitative—highlight the humanity of the incarcerated, and the absolute need for prison abolition. After all, the abhorrent conditions currently being faced by detained migrants is a direct extension of the grotesque, bloated prison industrial complex we’ve allowed to flourish in this country since the War on Drugs of the 1980s led to mass incarceration of people of color. We’ve enshrined the idea that imprisonment is the solution to society’s ills, rather than a contributing factor to it, and given policing bodies the authority—and weapons—to use force and discipline in place of amnesty and compassion.

“Lots of fine people have sat staring at the inside of prison walls,” Augustus (Harold Perrineau) tells the television audience in Oz, HBO’s groundbreaking series about life inside of a (fictional) maximum security state prison. “Socrates, Gandhi, Joan of Arc, Even our Lord Jesus Christ. He spent the last night of his life not with holy men, but with scum like the kind we've got in Oz. One of the last things Jesus did on earth was invite a prisoner to join him in heaven. He loved that criminal. I say, he loved that criminal as much as he loved anyone. Jesus knew in his heart it takes a lot to love a sinner. But the sinner, he needs it all the more.”

Imprisoned individuals are punitively kept separate from the outside world—housed in massive facilities in largely isolated, rural areas—but we are also kept separate from them, as if, once out of sight, the incarcerated will also be out of mind, their lives left to languish. It’s imperative that we do not let that happen.

I’m a big advocate of NYC Books Through Bars, which sends books to incarcerated individuals based on request; each month, they hold drives related to the types of literature they’re looking to fill and sell discounted donation bundles through their associate, Freebird Books. This month, in honor of their 5th anniversary, they’re filling LGBTQ material that, in their own words, “might not pass muster at the U.S. Naval Academy library, but that incarcerated readers are welcome to request and receive.” It’s a super easy way to provide something nice to a population lacking in easy access to art and educational literature, so very necessary, and something we’re lucky enough to take for granted. Send them some books for $30!

Oh My God, l Am Totally Buggin, l Feel Like Such a Bonehead: on “Hags” and “Gay Best Friends”

In Truman Capote’s iconic 1958 novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the unnamed protagonist reflects on the beautiful, brief relationship he maintains with a woman named Holly Golightly, a call girl with surprisingly progressive views on sexuality whom he comes to know a little bit while toiling away as a struggling writer. Upon learning of a potential marriage, he reflects, in the poorly-aged verbiage of his time, “Was my outrage the result of being in love with Holly myself? A little. For I was in love with her. Just as I’d once been in love with my mother’s elderly colored cook and a postman who let me follow him on his rounds and a whole family named McKendrick. That category of love generates jealousy, too.”

Breakfast at Tiffany’s would, of course, be turned into a hit feature film that made a generational star out of Audrey Hepburn, who gets to tear through some of Capote’s most effervescent dialogue; the protagonist would be given a name, and a romantic subplot with Holly. But Capote’s novella, inspired by his relationships with a number of fashionable young women—including Marilyn Monroe, whom he’d later call “a beautiful child”2 —captures something far more fascinating than heterosexual romance: the relationship between a gay man (like Capote) and his best girl friend. His “Good Judy,” a term of endearment in the gay community to connote someone you trust and have a special bond with: i.e. his bestie, his gal pal—there’s a particular phrase for it, used by past generations, which I won’t reprint here, as it contains a slur I don’t feel comfortable employing, no matter how much my Good Judy playfully goads me into doing so. I prefer the shorthand: hag. And this program is all about hags.

A lot has been made about the “gay best friend” stereotype that exploded onscreen in the 90s and early 2000s—likely a result of the mass popularity of groundbreaking premium cable comedy series Sex and the City (1998-2004), in which gay characters, with a few exceptions, were little more than sounding boards and cheap punchlines for its female characters, and Will & Grace (1998-2006), a situational comedy in which a straight woman moves in with her gay best friend after the collapse of her engagement. Awash with cultural stereotypes and over-the-top characters of all genders and sexualities (so, you know, network television), Will & Grace in particular was a mainstream (and obviously imperfect) reflection of a real cultural phenomenon particularly relevant to creative spaces and artistic fields, which tend to draw people to dense urban centers: the strong, pseudo-familial bonds that can form between gay men and women as a protective safety net against the vagaries and peculiarities of urban life. In the Will & Grace era, the “gay best friend” was everywhere, particularly in female-oriented romantic comedies, leading to a controversial shorthand (“my gay”) that suggests that gay men serve little more purpose in women’s lives than to comment, sassily, on the events of their lives and the clothes on their body. Darren Stein, a gay filmmaker best remembered for his queer-coded cult teen flick Jawbreaker (1999), even later canonized this fetishization in another teen flick, G.B.F. (2013), in which a closeted teen becomes instantly popular when he comes out, only to become a pawn for the young queen bees who believe having a gay bestie will bring them clout.

The “gay best friend” stereotype is surely an issue of positioning and genre convention as much as casual homophobia: in the media landscape of that era, films pitched to (and starring) women were largely romantic comedies, which generally sideline friendships in favor of heterosexual romance—the ultimate life goal within the limited imaginative scope of a heteronormative society. Gay protagonists, as well as gay friend circles, were largely relegated to queer media, which received less visibility, less funding, and less canonization within the critical and cultural landscape at large. This hurts characters in more ways than one: in addition to sidelining the “gay best friend,” it also suggests (again, with limited imagination) that these female best friends are straight themselves, rather than gay or bisexual, gawking at a community from the outside, rather than celebrating it from within. How much of the asinine “women don’t belong at gay clubs” discourse stems from this deep-rooted cultural idea that women with deep attachment to gay men must be parasitic, fetishistic vampires with no vested interest of their own in the ongoing fight against queer disenfranchisement?

The “gay best friend” archetype was not new to the late 90s/early 2000s—character actors like Edward Everett Horton (gay in real life) played (coded) gay friends in comedies of the 1930s; Tony Randall fills this same role in the Doris Day/Rock Hudson “no sex” sex comedies of the 1950s/60s; Katharine Hepburn kikis with her bitchy neighbor, David Wayne, in Adam’s Rib (1949); and pregnant women seeking out proverbial shelter from social stigma befriend young gay men in British kitchen sink classics A Taste of Honey (1961) and The L-Shaped Room (1962). Gay liberation brought gay stories out of the closet—but the cultural sidelining of gay life within mainstream media would continue for decades later. This creates a particular challenge for someone looking to create a diverse program on “hags”: how to celebrate this relationship—and honor its specificity—when so much film and television tokenizes and sidelines gay characters? In addition to canonizing the new media that openly reflects it, warts and all, it’s a little bit of weeding out the older worst offenders (so no Sex and the City), repositioning ostensibly heterosexual movies with pointed subtext,3 and going to bat for movies or shows that, while maybe imperfect, have something interesting to say about relationships that complicate or subvert heteronormative mores. In romantic comedy classic My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997), Rupert Everett (gay in real life) plays the seemingly stereotypical “gay best friend” to antiheroine Julia Roberts, whose misguided attempts at seduction of an old flame on the occasion of his wedding form a sort of false-flag premise on which to hook the audience. But the film, far smarter than anyone gives it credit for, ultimately suggests that Roberts’ happiness isn’t tethered to heterosexual romance at all, but to the rich, meaningful relationship she maintains with her platonic best friend, who, in spite of her considerable personal failings, loves her unconditionally. In the film’s swoon-worthy, romantic final moments, Everett arrives at the wedding to surprise the heroine in her romantic destitution. “Maybe there won't be marriage,” he reflects, pulling her to the dance floor. “Maybe there won't be sex: but, by God, there'll be dancing.” And isn’t that what all of us are really looking for in life: someone to simply hold our hand when we need it the most?

There is a true sense of romance in such protective, meaningful friendships. Yet the hag / bestie dynamic is as messy as any familial bond, stretching, as it must, to accommodate the peculiarities of the human heart, and the in-fighting that punctuates any relationship between two people who see each other so completely, warts and all. “Well you are,” the protagonist marvels in Capote’s novella, when Holly Golightly unceremoniously dumps her poor, no-name cat on the side of the road. “You are a bitch.” Capote’s own complicated relationship with childhood best friend Harper Lee is captured in two films in this program—Capote (2005) and Infamous (2006)—as is his infamous literary “betrayal” of the coterie of rich white women he palled around with in the 1960s, which wound up destroying his life and career, memorialized in Feud: Capote vs. The Swans (2024). Elsewhere, famously gay artist Andy Warhol (played by a ridiculously good Guy Pearce) loves, exploits, and abandons his troubled muse, Edie Sedgwick, in gloriously messy aughts misfire Factory Girl (2004); co-conspirators and celebrity wannabes Rebecca and Marc turn against each other in Sofia Coppola’s Bling Ring (2013); and alt comedians Kate Berlant and John Early play resentful, estranged costars from a faux-sitcom He’s Gay, She’s Jewish in their comedy special Would It Kill You to Laugh? (2022), a satirization of their own comedic brand. In some of the most delicious entries in this program, the gay man and his hag enable the worst impulses in one another, engendering an endless feedback loop of bitchy discourse and/or bad behavior. “You ruined me!” a young gay man (Max Jenkins) screams to his toxic, tokenizing roommate (Heléne Yorke)4 while high on meth in the first episode of HBO’s High Maintenance (2016). “You’d still be wearing bootcut jeans if it wasn’t for me!”

For all the romantic cadence of the bond between a hag and a gay man, sometimes the heterosexual iteration of the former, entitled and frustrated by that which cannot be hers, lashes out at the beautiful man she loves the most. “Yes, I have friends, but none of them need me, and yes, I have you, and if you weren't such a God-damned poof we could have all been happy!” Julianne Moore, in Gay Icon Mode, drunkenly squawks at her best friend, Colin Firth, a college professor failing to move on from the loss of his longtime lover in A Single Man (2009), Tom Ford’s adaptation of the 1964 Christopher Isherwood novel of the same name. (It’s an incredibly mean and pathetic outburst, but…so oddly human). And speaking of romantic entitlement, no gay man and his female bestie are as noxious or calculating as (queer-coded) columnist Addison DeWitt (George Sanders, bisexual in real life) is towards the (queer-coded) woman he claims to love, Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter), in (queer-coded) classic All About Eve. “You’re an improbable person, Eve, and so am I,” he sneers in a pivotal scene, in which he strips back the last bits of delusion between them. “We have that in common. Also, our contempt for humanity and inability to love, and be loved, insatiable ambition, and talent.”

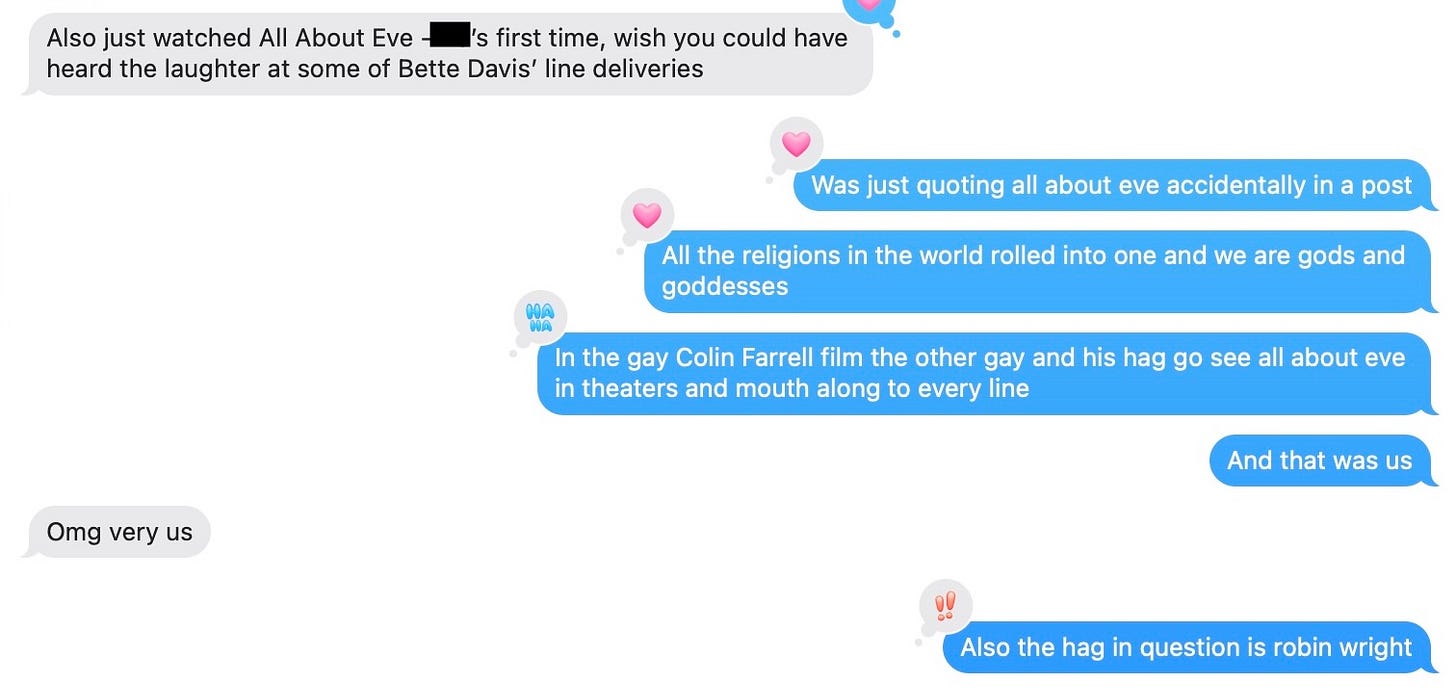

In the little-seen Colin Farrell-starring indie A Home at the End of the World (2004), a gay bohemian (Dallas Roberts) and his Good Judy (Robin Wright) attend a screening of All About Eve (1950), only to mouth along to every line, performing a ritual specific to their hermetically-sealed little world and speaking a referential language only used by those in the know. It’s the closest I’ve seen myself represented onscreen—well, that and the scene in The Family Stone (2005) in which Diane Keaton, a Great Judy, earnestly expresses the belief that she tried her to ensure that all of her children ended up gay.

This program, though titled “hags,” is really a love letter to all the beautiful, hilarious, thoughtful, ridiculous, catty, genius, earnest, outrageous, shy, mischievous, and/or heartfelt gay men who have enriched my life, held my hand, given me grace, taught me, broken my heart, and made life—forever undulating, never straightforward—a textured, beautiful cacophony that staves off boredom and gloom. This is for those fellow creatures that chase the Technicolor roads of Oz and speak the same strange, secret language, passed between artists and onlookers—I really would be an incredibly boring film critic without it.

“I just use common sense,” Edith Massey, another Mama Judy, tells a young gay man she’s courting for her (straight) son in John Waters’ Female Trouble (1974), reassuring him that her scion must be homosexual. “I mean, if they’re smart they're queer, and if they’re stupid they're straight, right?”

Hey I Heard You Were a Wild One (1953): Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando died in 2004, when I was 13 years old, meaning I was sentient—and tumbling into pubescence—when posthumous tributes came pouring in celebrating the legendary leading man as one of the greatest screen actors of all time, accompanied by photos showcasing the actor at the height of his popularity. This distinction is key, because it meant that I was suddenly inundated with images of the hottest man I’d ever seen in my life at a time when my hormones were rewiring my brain chemistry, shaping me into the oversexed woman I’d become. He snarled and mugged, totally electric, in a leather jacket and riding cap in promotional photos pulled from The Wild One (1953). He brooded in a tight undershirt carefully tailored, cut, and stained to emphasize his musculature in imagery lifted from A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Sure, The Godfather (1972) was mentioned, but all I cared about was the young, hot stud of the 1950s I was suddenly seeing everywhere—up until then, I’d gorged on the comparatively small, pretty boys of the new millennium, desire relegated to the realm of chaste fantasy. I’d marry Leonardo DiCaprio or Heath Ledger or JC Chasez and we’d…I don’t know; desire was an ellipsis, totally innocent and cerebral. But after Brando’s death brought me Brando, things changed. I watched all his old movies on TCM, and when I missed a showing of Streetcar Named Desire, I picked up a VHS (!) copy of the film at Dallas’ once-legendary home video mecca, Premiere Video.

The Weekend I Brought Home A Streetcar Named Desire From the Video Store—a pivotal event well-defined in my memory palace—I watched the film on a 12" television propped up on my bed, once…twice…three times…Rewound it; rewatched it, like the Zapruder film; went back again, each time discovering new little details to Brando’s performance I just had to see again: the way he lit a match on his shoe, or flexed while standing still, or seemed to chew gum, endlessly, like a cow with a cud, or screamed, like the world was ending, on the famous “Hey Stellaaaaaaa!” line reading. I didn’t want to return the film to the store at the end of the weekend: there was no YouTube yet, and we didn’t (yet) own the film. I panicked: how would I keep watching Brando without it? So I rewound the tapes (yet again) and recorded shitty, low-resolution videos of my favorite scenes on my flip phone (!), watching them in secret, late into the night, completely mesmerized. I didn’t yet understand that I was feeling desire—real, messy, sticky, adult desire—from a film named for the emotion, for the very first time. “What you are talking about is desire, just brutal desire,” Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) scolds her sister over the fraught relationship between her and husband (Brando), which is both abusive and incredibly carnal, in the film. “The name of that rattle-trap streetcar that bangs through the Quarter, up one old narrow street and down another.” And her sister, with a knowing look, asks in return, “Haven't you ever ridden on that streetcar?”

My sexual awakening was here. Aptly enough, it came courtesy of a sexually fraught melodrama written by a homosexual man.

Such an experience was not unique to yours truly, though it felt it at the time; many have similarly fallen under Brando’s spell. In Jeff Nichols’ underrated biker gang melodrama The Bikeriders (2023), Tom Hardy is so instantly transfixed by Brando’s performance in biker classic The Wild One (1953) that he decides to start a motorcycle club of his own. In a pointed scene that spells out the film’s homoerotic subtext, he ignores his wife to watch, in slack-eyed silence, as Brando, forever cool, snarls and struts through the movie, looking butch as hell. It’s an apt casting decision, given Tom Hardy’s now-iconic 2010 remark that “of course” he’s had gay sex, as he’s “an actor for fuck’s sake.” Such wisdom could speak to Marlon Brando’s own experiences as an openly bisexual actor5—and help to articulate his near-universal appeal. He was, in the parlance of our times, “for the community.” To hear the late Quincy Jones tell it, as he did in an instantly iconic tell-all interview to Vulture in 2018: “He’d fuck anything. Anything! He’d fuck a mailbox. James Baldwin. Richard Pryor. Marvin Gaye…He did not give a fuck!”

Everybody wanted a piece of Marlon Brando, or to be Marlon Brando, until they didn’t: famously consumed by his odd, reclusive behavior and personal shortcomings—including a penchant for overeating that was so significant, he allegedly used to break the locks off his own refrigerators in the middle of the night—he became an easy punchline towards the end of his life, just as his distinctive, raspy voice and showy performing style turned him into a parody of himself. The final ledger of his cinematic output is decidedly neutral: he made as many bad movies as good ones. But death is its own kind of rebirth, and in his death, he was able to escape the messiness of his personal and professional life. For those of us born too late to witness firsthand the many, many nadirs, it’s easy to idolize Brando as a scintillating icon of mid-century masculinity, a talented actor, a vocal ally to progressive causes like the Civil Rights and American Indian movements of the late 1960s, and the damn Godfather. We can cherry pick the best, and leave the rest. My feelings towards Brando, as a man and a performer, are more complicated than they were in the mid-aughts—when I watched all of his best movies and papered my walls and diaries with images of him, somehow both wanting to sleep with him (now, yes, I understood the feeling) and be him: cool, indifferent, rebellious, and undeniable. I’m more fascinated in the cult surrounding Brando, and the feelings he inspires in others, as part of a signification process through which they could understand their own gender identity: he was so much of a man that he helped define manhood for a generation of performers—including, most notably, James Dean, who developed a near-pathological psychosexual obsession with him, and Elvis Presley, who modeled his entire performing persona off of his work.6

Like Bob Dylan, “Brando” seemed to be born when he left a mysterious childhood for New York City, where he carved out his legacy as a fresh, radical presence. His mother was an alcoholic and his father was an abusive, often-absent salesmen: he allegedly channeled his father’s rage into the violent outbursts that punctuated his explosive performance in A Streetcar Named Desire, which made performing it night after night, to packed houses, difficult. A practitioner of the Stanislavski Method, which he learned while studying under Stella Adler at the New School, Brando began appearing on Broadway as early as 1944 (making his debut with I Remember Mama) and was part of the inaugural 1947 class of the Actor’s Studio, the same year he was cast as the male lead, Stanley Kowalski, in the original Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, replacing John Garfield, the original choice for the part. The Pulitzer Prize-winning play, directed by up-and-coming hot shot Elia Kazan, was a critical and commercial hit, then a cultural phenomenon. When Brando moved to Hollywood, it was bemoaned by intellectual circles who viewed it as a great artist selling out: after all, the performing style favored in Hollywood at that time was largely exaggerated and artificial, a far cry from the radically grounded work being done in the New York theater scene. Brando brought his “Method” performing style to his largely forgotten first feature, The Men (1950), in which he plays a paraplegic soldier recuperating in a veteran hospital with the same kind of sharply-channeled ennui that made him an instant-star in A Streetcar Named Desire—in real life, Brando was passed over for military service because of a knee injury; he spent time studying wounded veterans at a hospital in Los Angeles to prepare for the part. His second film, the feature adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire, also directed by Kazan, brought his acclaimed, transgressive performance of male entitlement and unfettered id to the rest of the country—earning him an Academy Award nomination and instant stardom in the process.

It’s easy to lump Brando’s early dramatic roles together to create a simplistic portrait of a tortured, brooding young genius—epitomized by his Oscar-winning performance in On the Waterfront (1954), in which he delivers the iconic “I Could Have Been a Contender” speech, which I delivered many, many times in the safety of my childhood bedroom. But Brando’s best early roles subvert or complicate this simplistic image of him as a mumbling Method baddie: consider his impressive turn as a beefcake Mark Antony in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1953), in which he blends in seamlessly with seasoned Shakespearean stage actors like James Mason and John Gielgud. His rendition of Anthony’s famous Forum and Dogs of War speeches, delivered with such heartfelt verve and passion, demonstrate why he was once the theater’s brightest rising light, despite coming from an entirely different school of acting. In Mankiewicz’ delightful film adaptation of the iconic stage musical, Guys and Dolls (1955), Brando snagged the flashy lead role of gambling womanizer Sky Masterson from Frank Sinatra, who was compelled to play against type as fast-talking loser Nathan Detroit instead—a switch that, in my humble opinion, forced Sinatra, a gifted comedic actor, to give one of his funniest performances. Brando wasn’t a singer by any means, but he had a nice little voice, and it’s so fun to watch him swagger and croon through the eye-catching, candy-colored studio sets of Guys and Dolls, particularly when he gets a chance to flex his considerable dance skills. “He could dance his ass off,” Quincy Jones, in that same 2018 interview, reflected, upon introducing the non-sequitur that he used to go cha-cha dancing with him. Sinatra, for all his effortless swagger and passable dancing in hokey Gene Kelly musicals, just wasn’t that sexy.

By the time of Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)—a critical flop that somewhat dubiously claimed Best Picture at the Academy Awards, despite winning in no other categories—Brando’s offscreen reputation as a problematic, troublesome performer consumed by his own improvisational, self-conscious performing style was beginning to significantly harm his image, as a host of other promising young actors with Method backgrounds (like Paul Newman and Warren Beatty) began to challenge his monopoly. By the mid-60s, the Old Hollywood Guard was losing ground to fresh voices and faces—and Brando was caught somewhere in between. For example, he worked with rising filmmaker Arthur Penn on The Chase (1966), a maligned, maybe-misunderstood flop that was the last movie the director made before exploding into the zeitgeist the following year with Bonnie and Clyde (1967), a smash hit that helped herald in the New Hollywood movement. The earlier film’s failure was the latest in a long string of critical and commercial disappointments for the performer, who, in looking to simply pay the bills, seemed to lose discernment in picking roles, more interested in offscreen activism—most famously, participating in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, lending his celebrity to the cause of racial equality. He seemed to grow disillusioned with the frivolity of his chosen profession—and trying to get up and go to work now, in 2025, against the backdrop of so much social and political strife, it’s at least a little understandable. Some of the failures of this turbulent era are truly noteworthy—like his fascinating turn as a closeted military officer who becomes psychosexually obsessed with a young Robert Forster in cinematic curio Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). Or the rich, textural Southwestern landscape captured in his western The Appaloosa (1966), shot in staggering Techniscope by legendary cinematographer—and Douglas Sirk’s go-to D.P.— Russell Metty, maestro of Technicolor. Or even Brando’s sole directorial effort, One-Eyed Jacks (1961), a bizarre (and endlessly watchable) fusion of Method acting, Old West schmaltz, and lurid psychosexual dysfunction. But a lot of his 60s movies are, quite frankly, unbearable, and he’s unbearable in them.

By the early 1970s, Marlon Brando, like Elvis before him, had become a joke and a has-been: his performance in The Nightcomers (1971), Michael Winner’s BDSM-soaked prequel to Henry James’ The Taming of the Shrew—better-appreciated these days—saw him stumbling over a bad Irish accent, bloated and balding yet still determined to be a sex icon. People viewed it as totally pathetic. It took a stunning, seemingly impossible act of professional reinvention in 1972 to return the troubled performer to his former glory, and reintroduce his legacy for a new generation: his Oscar-winning performance in The Godfather (1972). So much lore exists about Francis Ford Coppola’s magnum opus (if you believe it to be better than Godfather Part II, which I personally do not), and Brando’s performance in particular—the cotton balls in his jowls, the accent, the cue cards on Robert Duvall’s chest—that there’s not much interesting to add; its legacy and legendary production has formed the basis for books, television documentaries, and television series. And I actually find that Brando’s showy performance pales in comparison to the comparatively nuanced, quiet intensity of (spiritual successor) Al Pacino’s performance as his son, who transforms over the course of the film from a man of character to a man of violence. Perhaps that’s closest to how I view Brando now: as a performer who inspired others to further refine the disruptive, uncontrollable energy he brought to film. In my humble estimation, he paved the way for others to do it better, and more consistently.

But the film that most complicated my youthful love for Brando is his groundbreaking other movie from that year: Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), a movie so controversial on release that it resulted in obscenity charges in the director’s native country of Italy, where he was stripped of his voting rights for five years in punishment. Though widely understood as a considerable artistic achievement that pushed the boundaries of onscreen sex, the film remains infamous to this day because of the behind-the-scenes treatment of its leading lady, Maria Schneider, who later claimed that she was blindsided by the film’s infamous rape scene—allegedly Brando’s idea—in which butter is crudely introduced as a lubricant; the scene’s infamy, as well as the notoriety it brought her, apparently drove her deep into depression. Schneider’s oft-cited 2007 interview with the Daily Mail included the quote, “I felt humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci,” which have led some to claim that the experience was sexual assault—even though she clarifies in the same interview that all of the sex was simulated. The incident was, however, a significant violation of Schneider’s boundaries as a performer in a toxic, misogynistic working environment, and Brando’s actions and complicity—which he never apologized for—reflect the worst impulses of his brand of Method Acting, in which everything falls at the altar of the Tortured Male Genius, enabling bad behavior regardless of the collateral damage. No performer deserves to be psychologically tortured, abused, or feel violated in the service of making a film, and the farther we get from unchecked Brando fetishism and the kind of old-hat thinking that suggests otherwise, the better off we are. To cite a famous quote from Laurence Olivier levied at a different actor inspired and enabled by Brando’s Method legacy: “Why don’t you just try acting?”

Brando had a few more acclaimed roles after The Godfather (1972) revitalized his career, even after he famously rejected his Oscar, in a legendary, bold act of solidarity with the American Indian Movement that alienated old heads in the industry. His mumbling Colonel Kurtz, however hard-won behind-the-scenes, is an iconic part of Coppola’s classic Vietnam movie Apocalypse Now (1979); Superman (1978), in which he plays the hero’s birth father, was a massive critical and commercial hit of its time; and he even earned another Oscar nomination for his supporting performance in A Dry White Season (1989), playing a human rights lawyer trying an impossible case of racially-motivated murder from within the corrupt legal system of apartheid-era South Africa. He even gained a little late-career shine parodying his own screen persona, and acting opposite his spiritual sons, in successful, generally well-liked movies like The Freshman (1990), Don Juan DeMarco (1995), and The Score (2001), his final film role. But these successes were interspersed with the infamy of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), responsible for one of the most notorious film sets in modern history (in no small part thanks to Brando’s actions), and the never-released Johnny Depp-directed cinematic disaster The Brave (1997). His actual final role, voicing an old woman in an animated Brendan Fraser movie about a man who gains insect powers, Big Bug Man, was—perhaps blessedly—also never released. He died a month after recording his lines, and I’m not saying the experience killed him, but it certainly couldn’t have helped.

“Time liberates the art from moral relevance,” Susan Sontag wrote in her iconic, oft-debated treatise on Camp sensibility from her essay collection Against Interpretation. “Thus, things are campy, not when they become old—but when we become less involved in them, and can enjoy, instead of be frustrated by, the failure of the attempt…Maybe ‘Method Acting’…will be same as Camp some day as Ruby Keeler’s does now…and maybe not.” And that’s generally how I feel about Brando’s style of performance these days. Brando’s worst impulses—his bizarre attachment to inscrutable accents, general lack of professionalism, ridiculous reliance on cue cards and ear pieces, and artistic laziness—now alienate me from the slavish devotion I once felt towards him as an excited, slightly naive young film fan. But I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t still fascinated by the idea of him as a kind of ultimate drag king: the blueprint for masculine posturing and performance, whose legacy is often whittled down to an easy parody. After his death, Brando’s ashes were mixed and scattered with his childhood friend, onetime roommate, and alleged lifetime love, Wally Cox, a man he was so steadfastly devoted to he used to talk nightly to an urn of his ashes—stolen from his widow—after the man’s death. That’s just a reminder, for anyone who tries to position Brando as some great straight male avatar due to his Godfather cult, of who the man playing him really was.

Plus: The Return of the Queer Cinema Canon

Last year for Pride, we formally debuted our Queer Cinema Canon: three massive lists (Essentials, Next Steps, and Deep Cuts) covering queer cinema classics, sorted by year. This year, all of the films (with a ton of new finds) are accessible in one master list, broken down into the same three categories with the up-to-date streaming information. Last year, we further divided films from each list into four informal categories by era: “Pre-1969: Pre-Stonewall,” “1969-1990: Visibility and Canonization,” “1991-2009: ‘New Queer Cinema’ and its Aftermath,” and “2010-Present: The ‘New Queer Classics’.” It’s a constantly growing, true labor of love, culled from endless pawing through old analog guides and film screenings. I hope that you find something new and/or unusual to love from it. There’s simply so much beauty in the world, despite the loud, ugly bellows of bigotry currently polluting our airspace; It’d be a shame to pay any of the rabble any mind. Happy Pride!

That’s all for June! Until next time, my beautiful ones. Rouge and coloring, incense and ice/ perfume and kisses, ooh, it's all so nice…

Inspired by Browder’s story, President Obama signed an executive order in 2016 to ban the use of solitary confinement in prison…on juveniles. Although President Biden passed an executive order in 2022 demanding the restriction of solitary confinement against all inmates, its use actually increased during his presidency. The “End Solitary Confinement Act” was introduced in Congress in 2023, but it seems highly unlikely to move forward under this administration.

Truman Capote excerpted an alleged conversation the pair had after the funeral of acting coach Constance Collier in his short story collection Music for Chameleons (1980). He describes Marilyn to Marilyn as someone who “wears her heart on her sleeve and talks salty.” Over the course of one extended, gossipy conversation fueled by champagne (an incident that may or may not be total bullshit), Monroe asks Capote what he’d say when asked what she was really like, prompting this response.

The Rock Hudson and Doris Day romantic comedies, for example, play with a certain amount of irony to modern audiences, who now know that Hudson was gay; the general sexlessness of these films and the rich offscreen friendship between the two stars lend the movies a vibe not dissimilar to the hag/gay man dynamic now openly depicted. Down with Love (2003), a parody of these movies, knowingly plays with this aspect of the movie—and has subtext given of its own, given that the “B” romance is played by two now-out actors, David Hyde Pierce and Sarah Paulson. The film adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), though reconfigured to be about a heterosexual romance, contains nearly all of the same interactions of—and dialogue between—the two queer-coded leads in Capote’s novella, which ensures that the platonic, kiki dynamic between the two characters remains.

Heléne Yorke is the de-facto queen of playing the toxic Judy, at least on HBO: she later embodies a similar character on cult comedy series The Other Two (2019-2023), in which a gay man and his sister engage in seriously questionable behavior in a desperate bid to be as famous as their younger brother, a viral social media star.

Like Hardy, Brando commented on his own bisexuality on record: per Gary Carey’s autobiography, Marlon Brando: The Only Contender, Brando told a French journalist in the 70s: “Homosexuality is so much in fashion, it no longer makes news. Like a large number of men, I, too, have had homosexual experiences, and I am not ashamed.”

Brando’s performance and appearance in The Wild One (1953) established the “rebel without a cause” persona that Dean and Elvis would cultivate on and offscreen and become synonymous with 50s “greaser” looks. In the film, he sports a now-iconic riding cap and riding gloves, as well as a Perfecto motorcycle jacket—a garment originally designed by Irving Schott that dates back to the 1920s. Brando’s was adorned with the iconic B.R.M.C., for “Black Rebel Motorcycle Club”; in real life, bikers would customize their own jackets to display their club or group affiliation.