Just the other day, on “X” (née Twitter), someone who pays for a blue verification check posted a vintage photo of Carole Lombard and Clark Gable—the latter sporting the distinctive fez of the Shriners, face scrunched up in haughty charm, alongside the caption, “CLARK GABLE. 33RD MASON AND SHRINER. WAS HIS WIFE, CAROLE LOMBARD, WHO WAS KILLED IN A PLANE CRASH, HIS SACRIFICE?” (It’s all happening on X, the everything app!) I was floored by this accidental (and timely) brush with conspiracy: I’d been knee-deep in Masonic lore for weeks, prepping this newsletter, but it never even occurred to me to unearth all the theories of human sacrifice: I was, like a real jerk-off, too concerned with the banal, real-life ways Freemasonry connects aspirational white men to one another in a concerted effort to build cultural hegemony and geopolitical dominance. This is frequently my problem: it feels like nobody wants to interrogate shadowy systems of power without getting Globalist conspiracy brained. And, regardless of what my parents’ Dallas-area neighbors might think about that one time I went off at dinner about Lee Harvey Oswald—ignoring that he defected to the Soviet Union, renouncing his U.S. citizenship, and we’re just expected to believe that they let him back in (??)—I’m a normal American woman, with two feet planted firmly in reality.

Welcome to May streaming.

When Freemason J. Edgar Hoover received the Medal for Distinguished Achievement from the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York in May 1950, presented at a black-tie dinner at the Hotel Astor, the now-infamous FBI director took the opportunity to praise the Masonic influence on the Founding Fathers, who “under the divine genius of the supreme architect of the universe, did their work well” (like hiding all those clues in our national documents to hide that big treasure). Under Hoover’s hand, FBI men, courted largely from the man’s own fraternity, Kappa Alpha—an organization whose mission, incidentally is/was to uphold white supremacy—were highly encouraged to join the bureau’s own Masonic chapter, the Fidelity Club.

Hoover joined Federal Lodge No. 1 in 1920, shortly after he was named head of the General Intelligence Division at the Justice Department’s then-titled “Bureau of Investigation.” In late 1919, GID, the so-called “Radical Division,” arrested, incarcerated, and deported immigrants, anarchists, and labor activists as part of a larger xenophobic effort to expunge “radical elements” from the fabric of American life, all in the name of public safety and security. The Palmer Raids, named for Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, marked the first “Red Scare” in 20th century American history: thousands of people were arrested, typically without warrants, in dozens of cities across the country. In some places, detainees were held in captivity for months without access to a lawyer or any knowledge of the charges against them; others faced serious abuse in their incarceration, including starvation. Ultimately, 556 people were deported under the aegis of the Sedition Act of 1918, a wartime statute that specifically forbade critique of the U.S. Government, later repealed in 1920.1

If the eerie symmetry to our present moment is not yet obvious, consider that this series of events directly led to the creation of the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization currently engaged in a real-time legal struggle with the Trump administration over its mass deportation efforts, a campaign of cruelty without due process that relies on the dehumanization and othering of immigrants. The Palmer Raids, a mass overreach by the justice department and a serious violation of constitutional rights, was a major embarrassment for the nascent Bureau of Investigation, though Hoover himself weathered the storm of scandal (but never forgot the humiliation): in 1924, he was appointed director of the bureau and in 1935, the department was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1955, at the height of the Second Red Scare, J. Edgar Hoover, its most significant architect, was named a 33rd degree Mason by the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite Southern Masonic Jurisdiction of the United States, its top rank and highest honor. And if his duties truly did require human sacrifice, well, he did his work well. And then some.

Yes, it’s May, and, in honor of the significance the month holds in the history of the labor movement, we’re all fired up with a host of programs about power, protest, and all the crazy shit that goes down in that little stretch of swamp along the Potomac. To consider who wields power, one should probably consider how they came about it. How are the titans of industry and government determined and ordained in this country? Why, in hallowed halls and subterranean rooms, under the safe cover of cloaks and ancient, silly rituals that mask the very real consolidation of power they represent! Our main program, “Fraternity,” looks at the largely homosocial male environments entrenched in our culture that allow networking away from watchful eyes—and ensure that an elite section of people always come out on top. Then, for our actors showcase, we’ve got career retrospectives on two sex symbols who found themselves blacklisted for expressing support for progressive causes; one overcame it, triumphantly; the other did not, quite tragically. Both were, incidentally, subjects of tremendous songs: one, by the greatest country troubadour of the late 20th century; the other, by, well, Mickey Avalon.

Finally, a deep dive on the cultural depiction of Maryland, a state which, incidentally, tried to ban one of this month’s featured actors, calling for a boycott of her films in 1973, while the man that she once successfully sued for unlawful surveillance was scrambling to cover up one of the biggest political scandals of the 20th century. And in that spirit, we have our annual, regularly updated repository of progressive films.

So let’s lock in. You know, with my brains and your looks, we could go places…

The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man: “Fraternity” on Film

Fraternal orders—with their bizarre rituals, insular iconography, and serious real estate—practically invite the attention of conspiracy theorists: why else would modern men willingly assemble before a giant owl, as they do at The Bohemian Grove, the “gentlemen’s club” resort grounds that saw the birth of the Manhattan Project, were it not all part of some global conspiracy by elites to shape the world in their favor? Really, the theatricality of such insular male spaces distract from the dull truth at the heart of their construction: these fraternal organizations have historically existed to manage and consecrate power of a small group of white men, by putting them in contact with—and keeping them loyal to—each other.

In Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), William King Hale (Robert De Niro) takes his nephew, Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio), to a Masonic Lodge to confront him over his failure to curtail his headstrong Osage wife, paddling him into submission; the checkerboard floor, an architectural trademark of such spaces, reflecting back up into his glasses.2 The sequence is a subtle way of illustrating the consolidation of power in the Oklahoma territories, and the larger structures that operate, in secret, to uphold white supremacy through race-exclusive fraternal orders, which serve to incubate powerful men in honor-bound “brotherhoods.” Their actions are part of a larger, and far more sinister, design: manifest destiny by a secretive route. “You have to be a member to drink here,” Brad Dourif, a southern deputy (and secret Klansman), tells visiting FBI agent Gene Hackman, in town to investigate the murder of civil rights activists, in Mississippi Burning (1988). When pressed to clarify: a member of what, he says, after a pregnant pause, “Member of the social club.”

The Knights of Columbus, the Catholic version of the Masons, ban partisan political involvement, but they do allow advocacy on issues potentially of interest to Catholics, which is how the fraternal order has mobilized its members and lobbied around issues like abortion and gay marriage for decades—they even got “under God” added to the Pledge of Allegiance during the height of the Red Scare. They also directly fund pregnancy “crisis centers,” which prey on pregnant women through a combination of anti-abortion hysteria and medical misinformation in the guise of legitimate healthcare providers (they are not, and are thus not subject to HIPAA, nor legally compelled to provide accurate information). These are deep, well-lined pockets we’re dealing with. This is Old World money moving on behalf of Old Time Religion.

I’m not suggesting that all spaces in which men convene to socialize and connect with one another are fronts for nefarious activity and secretive political mobilization that directly negatively impact other marginalized and/or vulnerable groups, but when such meetings take place in secret, governed by codes of silence, well, how are we to know they aren’t?

When The Fast and the Furious director Rob Cohen made The Skulls (2000), a popcorn thriller inspired by the secretive Skulls and Bones society at Yale that counts three U.S. presidents as its members (William Howard Taft, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush) it was met with critical derision, something he later pushed back against: “I had in my mind that I was telling the story of George Senior and George W. Bush...and I thought this is how the elite functions. This is how the elite knits together these bonds that take them through life and keep them in the elite heights of any society...It's interesting how many of the critics missed this and didn’t understand it and blowed it off [sic] as silly.” Coming from Harvard graduate Cohen—not such a good dude, it seems— this should perhaps be taken with a grain of salt, but he has a point: several members of the Skull and Bones, for example, became key figures of the Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.) the wartime global intelligence agency that eventually became the C.I.A., whose strategic actions abroad, which tend to benefit the vested interests of the United States of America, are done without any public oversight, in total secrecy. Intelligence was sort of a Yale thing, actually, but not in a spooky way. Per the Yale Daily News: in the Yale graduating class of 1943, at least 42 members entered intelligence work. “It was very much an Ivy League operation,” Gaddis Smith, historian, told the paper. “It was kind of an elite club of often very wealthy people, but also people who were…in the social register.”

But maybe the truth really is more banal than sinister—my favorite allegation about Skull and Bones comes courtesy The Atlantic: “World domination aside, the most pervasive rumors about Bones are that initiates must masturbate in a coffin while recounting their sexual exploits, and that their candor is ultimately rewarded with a no-strings-attached gift of $15,000.”

Imagine three U.S. Presidents doing that. Imagine it, right now. Even Taft. Yes, the one that got stuck in the bathtub.

This program is all about fraternity, the ties that bind men together: in lodges, fraternities, armies, club houses, religious organizations, secret societies, criminal sex rings, knighthoods, and social orders. These are the all-male environments that produce, shape, refine, and politically align the men of this world, creating the masters of tomorrow. Hazing, crusades, grown men in robes of all colors, fight clubs (like that would ever happen), Freemason symbols and conspiracy, conclaves, orgies, bullfighting, skydiving, “fagging” (not my term!), and serial murder—this program has got it all, in all of the myriad of ways that men have organized themselves to preserve a white male-dominated society, resistant to any wave of social change.

In The Good Shepherd (2002), Robert De Niro’s abstracted biopic about James Jesus Angleton—a “Bonesman,” and one of the founding figures of the CIA—Joe Pesci plays an approximation of Sam Giancana, the Chicago mobster recruited by the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro. In a meeting with the fictionalized version of Angleton (Matt Damon), who levies the threat of deportation against him, Pesci discusses the values that each marginalized ethnic group possesses, despite their social disenfranchisement. When asked in response what his people “have,” the white CIA man responds, “The United States of America. The rest of you are just visiting.”

He Ran All the Way: The Marred Legacy of John Garfield

When “New York Historical,” the new tag for the New York Historical Society, launches Blacklisted: An American Story next month, the exhibition—which details the history and impact of the Hollywood Red Scare—will include a portrait of John Garfield done by his daughter, Julie Garfield, as well as several posters of the talented actor’s many famous films. “People were destroyed because of their beliefs,” Julie Garfield told the New York Times of the exhibit: it has long been the belief of the Garfield family that the Hollywood Red Scare, in which individuals named as political subversives by Congress were barred from working in Hollywood, directly led to the premature death of John Garfield, at age 39, from a heart attack.

Garfield, who devoted considerable time and money to progressive causes throughout his life, was one of the biggest sacrificial lambs of the Hollywood Blacklist. He was a major Hollywood star at the time of his subpoena by House Un-American Activities Committee, which oversaw the hearings into Communist “influence” in Hollywood, and his career was cut short after he failed to co-operate—stalling, playing dumb, and outright lying in his official appearance, effectively refusing to “name names” of Communist Party leaders. His professional ruin signaled to other, smaller performers that anyone could be barred from working should they run afoul of the suits in charge: best to fall in line and cooperate. But if the government was looking for a man who would simply roll over and spill his guts, they pegged the wrong guy. Garfield was a man of character, whose childhood on the streets of New York City instilled in him a definite code, one best articulated by Robert De Niro, one of his spiritual successors, in Goodfellas (1990): “Never rat on your friends and always keep your mouth shut.” Popular lore claims Garfield was preparing to name names at the time of his death; his family has never believed it.

At a production meeting for Body and Soul (1947), the hit boxing movie Garfield made under his own production company that later served as a particular influence on Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), he was asked why he insisted on casting Canada Lee, a progressive Black actor, in a key, non-stereotypical role as a former boxing champion, knowing that it would court controversy. His cutting response mirrored one given during an incident in 1952, in which the FBI promised to resolve his “professional problems” if he signed a statement swearing that his then-estranged wife was a member of the Communist Party:

“Fuck you.”

Garfield’s life may or may not have been cut short by the Hollywood Blacklist (a childhood bout of scarlet fever left him with a weak heart that also kept him out of wartime service), but his career, and subsequent legacy, certainly were: today, he lacks the dedicated fandom of actors like Marlon Brando, James Dean, Al Pacino, or Bob De Niro, even though all of those performers inarguably owe their celebrity and particular brand of Method acting to Garfield’s influence. Born Jacob Julius Garfinkle, the street-kid turned theater actor mixed dangerous volatility with vulnerability, tearing through lines with an accent that distinctly tied him to urban life. This formula had been done before, at Warner Bros., which specialized in just such a type of leading man—James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, and Paul Muni were all stars under contract at the studio. But none of them, quite frankly, were sexy, like Garfield was sexy. Garfield stood at just 5’7”—in pictures, he performed atop his self-proclaimed “man maker,” a box that made him appear bigger; there were better-looking stars, even sexier stars, but none of them married danger and menace with romantic allure like Garfield, whose film career lasted little more than a decade. He was the first modern sex symbol on-screen: his raw sex appeal, rugged good looks, and menacing eroticism made him an incredibly popular leading man in his time, and a whole new kind of Hollywood celebrity. He was Method before Method: a student of the American Laboratory Theater in New York, which was run by graduates of the Moscow Art Theater, Garfield trained in the acting exercises that would later form the basis of Method Acting, working alongside Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler, who would go on to train the first generation of “Method Actors” like Brando and Montgomery Clift.

The American Laboratory disbanded in 1933, but it’s many of its cohorts joined the Group Theatre, a coalition of progressive and Communist creatives who combined their personal leftist politics with their art, creating incendiary, anticapitalist works that captured the anger and ennui of the Depression era. Later, Garfield’s association with this organization would land him before HUAC, even though the actor himself apparently wasn’t much of an ideologue (his wife, Roberta, seems to have been the true ideological leftist). Garfield’s performances in plays by the Group Theatre cast him as “the angry young man,” torn asunder by global capitalism, even though offstage, he wasn’t taken particularly seriously by his dedicated cohorts, including playwright Clifford Odets, a lifelong friend, who later named names before Congress (Garfield actually died just one day after his friendly testimony). Garfield earned a Hollywood screen test off the strength of his work in the Group Theatre, an opportunity he was reluctant to take, but forced to endure out of economic necessity. No one could have predicted that he’d become an instant, bankable star off the force of his first screen appearance, but audiences immediately loved him. An Academy Award nomination followed, and Warner Bros. stuck him in six movies in 1939 alone, just to take advantage.

From the moment Garfield appears onscreen in his first film, Four Daughters (1938), a romantic melodrama about a composer (Claude Rains) and his, well, four daughters, he’s the only thing in the universe that matters. There’s just something about him that radiates sex: laconic, indifferent, cynical, and too smart for his own good, he tears through the artificial trappings of the corny movie he’s stuck in like he’s stepping right out of our own world, unwashed and tousled and puffing like a chimney. He’s the only real thing anywhere in the movie.

A nation of instantly aroused women took notice. After his breakthrough, Garfield plugged away for several years in studio fare, playing various iterations of his streetwise persona, though he balked at the parts he got and frequently found himself in contract suspension over his refusal to take certain pictures. Some of his films from this period are legitimate studio classics—like The Sea Wolf (1941), an atmospheric adaptation of Jack London’s 1904 novel, consciously rewritten as an allegory against fascism, or The Fallen Sparrow (1943), in which Garfield plays a jailed republican fighter at a time when the State Department wasn’t keen on insulting fascist Francoist Spain, our geopolitical ally. I’m a particular fan of Between Two Worlds (1944), a melancholy wartime film in which Garfield is one of several passengers aboard a mysterious ship awaiting judgement (doled out by Sydney Greenstreet!) after death. Some of these movies are not so great; and some of these movies, as was the fashion, bizarrely use Garfield’s Jewish ethnicity as a hall pass for ethnic pantomime—in the gorgeously overwrought Juarez (1939), in which he plays Mexican revolutionary Porfirio Díaz (!), and Tortilla Flat (1942), which turns him, Hedy Lamarr, and Spencer Tracy (!) into Mexican-Americans in Northern California. In a way, it’s sort of the essential Garfield persona: always othered, always on the outside looking in.

The best of Garfield’s work came towards the end of his Warner Bros. contract: his incredibly modern portrayal of a man blinded by combat in Pride of the Marines (1945) is a comparatively rich depiction of PTSD at a time when it was still-known as “Combat Stress Reaction” (CSR), or “battle fatigue.” But it was the following year that Garfield would really reach the apex of his creative and commercial powers: first, with a massive box office hit, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). Now regarded as one of the greatest film noirs of all time, The Postman Always Rings Twice was seismic on release, thanks to the combined sex appeal of its two ridiculously attractive leads: Lana Turner, bleached blonde and perversely festooned in crisp, all-white attire, and John Garfield, frequently shirtless and soaked with sweat, a volcano waiting to explode. They play a couple who conspire to kill the former’s husband in a bid to start a new life together, though nothing goes quite as they planned: it's as if the force of their sexual attraction is so all-encompassing, it exists entirely outside their control (an unwieldy attraction that continued offscreen, leading to an affair between the two stars). It’s the barebones structure supporting every erotic thriller to come: this thing between them will not be denied, even if it leads—as it must, under the Production Code—to their eventual destruction. Nobody Lives Forever (1946), another noir penned by cult novelist/screenwriter W. R. Burnett, brought Garfield together with director Jean Negulesco, who he’d go on to work with on one of his finest films, Humoresque (1946). A lovely music-themed melodrama, Humoresque pits Garfield, a promising violinist from the streets, with a beautiful, insecure patroness, Joan Crawford, on a doomed path of mutually-assured destruction. Equally world-weary, the two icons have scintillating sexual chemistry that crackles and pops (and I mean pops): “I'd like to slap your face,” Crawford snarls at her resentful boy toy. “Why don't you try it?” he fires back, quick as ever, without missing a beat; she smashes a glass against the wall in frustration. It’s hot.

After the success of The Postman Always Rings Twice, Garfield had unparalleled power in Hollywood, and he wielded it: not by extending his own studio contract, but by forming his own production company, Enterprise Productions. With it, he made the tremendous Body and Soul (1947), in which he plays an amateur boxer who rises the through ranks, only to fall victim to capitalism, manifested in-film by shady, corrupt promoters and fixed matches. A massive hit, the film begat a whirlwind of creative success for the leading man, though really it was the beginning of the end of his life and career: the film would come to be defined in nearly every way by the Hollywood Blacklist, as virtually everyone associated with it would find themselves in hot water with HUAC over the next few years, including the director, Robert Rossen, screenwriter Abe Polonsky, and several actors involved in the film (like the aforementioned Canada Lee). The next (and last) film Garfield made through his production company was Force of Evil (1948), a lurid, tremendous noir about a crooked lawyer who gets caught up in the numbers racket while trying to support his brother; nowadays, it’s regarded as one of the greatest film noirs of the era, but it was a failure in its own time, probably because, liberated from the studio system, the film was able to take the creative risks that made it so ahead of its own time. The Breaking Point (1950), a second, less-famous (but terrific in its own right) adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not, completely flopped, eclipsed by the actor’s offscreen troubles; by that point, you could practically see the toll taken by the performer’s offscreen stress on his face, imbuing his performance with a heartbreaking sense of borrowed time. His last and final film performance would be the aptly named He Ran All the Way (1951), a sweaty, frantic film about a petty thug who hides out in the home of Shelley Winters, outrunning the inevitable, with Garfield embodying a character so markedly different than his usual constructions: instead of the cool, calm guy of the streets, he's a pathetic, floundering individual, unable to accept the writing on the wall—it’s a terrific, if heartbreaking, final appearance. It feels like the actor is outrunning his own end, trying to stave off the larger forces closing in on him, just as the police close in on his character. By the time of the film’s delayed release, director John Berry and Hollywood Ten screenwriter Dalton Trumbo went uncredited, as they had already been blacklisted for refusing to cooperate with HUAC; Garfield would be dead less than a year after its release.

At the time of his death, he couldn’t even get a part on television. At the same time, two young Method actors were making names for themselves in Hollywood, graduates of the inaugural class of the Actor’s Studio, founded in 1947 by Group Theatre members Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford, and Robert Lewis: Montgomery Clift broke through to leading man status with his dishy antihero performance in A Place in the Sun (1951); a month later, the film adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), starring the young man who originated the menacing lead role on Broadway, made an overnight star of Marlon Brando. Garfield died on May 12, 1952, two months and a day to the 24th Academy Awards, where both young men were up for Best Actor.

Sunrise, sunset.3

A “Stupid Fucking Actress”: Jane Fonda through the Years

When Jane Fonda was still a child, she once encountered her mother, Frances, the second of screen icon Henry Fonda’s five wives, staring at herself in the mirror. Addressing her daughter, the troubled matriarch told her, “If I gain any extra weight, I’m going to cut it off with a knife.”

If the mirror stage marks the moment an infant recognizes themself in the mirror, and understands that they are distinctly separate from their parent, surely, in this moment with her mother at the mirror, Fonda saw only their similarities. Like her mother, she’d struggle with mental health issues and terrible body dysmorphia most of her adult life; like her mother, she’d get stuck under the thumb of controlling men who would always find her wanting, including Henry Fonda. Her mother, born near the beginning of the century, was a victim, plagued by a bipolar condition at a time when “hysterical” women were treated as wasted goods and excess baggage, lobotomized and locked away in sanitariums: tragically, she died by suicide when Jane was still just a preteen. She learned the true story of her mother’s death from an issue of Photoplay magazine. Jane, blessedly still with us at 87 years old, came into a deeply sexist world that punished difficult women—even the most privileged ones—became more difficult, and faced the consequences for it. Her journey to self-actualization, painted as spoiled, infantile entitlement by her critics, was (and remains) fucking badass.

Fonda has been called many things throughout her career: a bimbo—for her kittenish appearances in French erotic movies of the 1960s—a traitor—for her unapologetic condemnation of the Vietnam War and antiwar work—an idiot—for her perceived vapidity, deeply rooted in sexist attitudes towards outspoken women—and a sell-out, for her late-career pivot to shilling workout tapes. But she was, and is, to this day, an icon. A survivor. A role model.

She kicked open the door for all of us to be the kind of women we want to be, on our own terms. Others felt differently about it.

“She wasn’t that smart,” journalist David Halberstam remarked of the press conference Fonda held after visiting North Vietnam, a visit that included firsthand documentation of an ongoing U.S. war crime, eclipsed by her sensationalized “Hanoi Jane” photoshoot, in which she posed atop an anti-aircraft gun at the behest of her hosts. “And she was in way over her head. I’ve been in ‘Nam. Fonda isn’t a politician. She’s a movie star: a stupid fucking actress.”

Fonda, the greatest nepo baby in Hollywood history, was born into every conceivable privilege: she came into this world while her famous father was shooting Jezebel (1938), the film that would make him a star, ensuring that she’d come of age with a famous name that could open all kind of doors. Wealthy, beautiful, and well-labeled from square one, it seems inconceivable that Fonda would want for anything. But Fonda’s desire for perfectionism led to a lifetime of insecurities and neurotic obsessions, chiefly with her weight, which she maintained through a lifelong addiction to binging and purging, ballet, dexedrine, and chain-smoking. The pre-fame Plain American Jane—a fashion model turned aspiring theatrical actress who found herself being molded by a fascistic little Svengali named Andréas Voutsinas—is captured in a little-seen documentary shot by the legendary filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker, simply titled Jane (1962). Capturing the creative process and opening night of Fonda’s disastrous Broadway show The Fun Couple, the movie captures Fonda’s insecurity and vulnerability as a young performer: she’s completely precarious, yet totally dedicated to her craft, displaying that odd intensity that would make her such a compelling leading lady. Fonda had Hollywood hits during this period—Period of Adjustment (1962), which brought her a Golden Globe nomination; Walk on the Wild Side (1962), which put her slinky figure on the poster over other, more famous names; the Mad Men-style sex shenanigans of Sunday in New York (1963); and the dreadful Cat Ballou (1965), in which she served cunt in an interminable, egregiously goofy Western farce.

Creatively, Fonda found the projects offered by Hollywood unfulfilling and moved to Paris, where she took up with a coterie of intellectuals and artists who, while all leaning left, could not overcome their interminable Frenchness to fight le racisme or le general shittiness towards women. Here she met, fell in love with, and worked collaboratively with prolifically horny filmmaker Roger Vadim, who cast his (eventual) wife (and mother of his child) in his incredibly erotic films, reinventing her in the image of his famous French exes Brigitte Bardot and Catherine Deneuve (who apparently stayed on with the pair well into their relationship). None of these films are remembered today beyond Barbarella (1968), a groundbreaking cult film—based on a French comic serial of the same name—about an innocent yet wanton space sex goddess who dons a series of leotards and thigh high boots to travel the galaxy. Adrift in space, Barbarella is ignorant of the ways of sex, yet soon finds out, narrowly escaping sexual violence at every turn and finding legitimate romance in the arms of a winged angel (John Phillip Law). There’s an orgasm torture machine that Fonda breaks…it’s all late ‘60s Camp and excess, but it made Fonda, who is genuinely funny and beguiling in the role, a generational sex symbol—something that soon became became a vice. As the popular thinking goes, Fonda’s pivot to progressive activism in the late 1960s proved so controversial because men coveted her as Barbarella—perennially available, endlessly pliable—and hated the “shrew” she proved herself to be by loudly, proudly using her voice to draw attention to social inequalities.

Although Fonda had grown up around progressive politics—her father’s own Liberal beliefs, her brother Peter’s involvement with the counterculture, and the influence of left-leaning friends like Robert Redford and Simone Signoret—her real political reckoning began after the fighting in Vietnam intensified in the late 1960s. The My Lai massacre of 1968, in which U.S. soldiers mutilated, raped, and murdered hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese civilians, proved a major turning point in public perception of the war and Fonda—stuck in bed due to a difficult pregnancy with her daughter Vanessa—had nothing to do but read the news, horrified. Stateside, Fonda had scored a major hit with Barefoot in the Park (1967), a delightful romantic comedy co-starring Redford adapted from a Neil Simon play, which gave her enough cachet to secure a part in They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969). In her personal life, she began involving herself materially in the antiwar effort, attending lectures, protests, and actions, as well as donating time and resources to civil rights groups, including the nascent Black Panther Party—putting her own obligations towards motherhood on pause, divorcing Vadim, and moving back to California.

With They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969), Fonda entered a new period of creative and professional stimulation that she hadn’t yet experienced as a young actor. Working collaboratively with director Sydney Pollack, she developed her character—a desperate, hard-edged competitor in a Great Depression-era, all-night “dance competition,” in which the last couple standing wins a cash prize—with concerted and deliberate thoughtfulness, shaped by her own emerging political consciousness. By her own admission, it was the first time a director valued her feedback in developing a role, and it paid off: it earned her the first of seven Academy Award nominations and brought her Klute (1971), the first of two Best Actress wins. In Klute, Fonda plays a fashion model who moonlights as a sex worker by night, only to get caught up in a conspiracy involving an obsessed john and a police detective played by Donald Sutherland (with whom she’d begin an offscreen affair). Fonda developed the character based on on-the-ground research—spending time with real sex workers on jobs—as well as her own feelings about herself and her body; in total defiance of her Barbarella image, she cut her famous long locks into an unglamorous asymmetrical shag, a reflection of her shifting priorities and burgeoning feminist awakening. Completely unvarnished, her performance in Klute is mesmerizing: a mix of vulnerability and strength, a refreshingly nuanced look at sex work that eschews the standard stereotypes.

Fonda’s performance was so good, she won the Oscar despite the increasing infamy of her offscreen activism, which made her a target of FBI surveillance, estranged her from many in Hollywood, including her father,4 and threatened her career. A year after winning an Academy Award, she couldn’t get a job in Hollywood. In France, she lent her Hollywood status to Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Maoist satire of the left, Tout Va Bien (1972), which premiered at New York Film Festival with an accompanying coda: Letter to Jane (1972), a corny featurette centered around the infamous photo of Fonda atop an anti-aircraft gun in North Vietnam, attacking her as a bad political actor. Meanwhile, she was building FTA—or “Fuck Free the Army,” a series of shows she developed with boyfriend Donald Sutherland and actor Peter Boyle as a means of politically engaging—and entertaining—troops. A kind of parody of Bob Hope’s jingoistic USO tours, the shows took place at coffee houses near army bases, since the military refused to let them stage it officially. A movie capturing their tour, FTA (1972), was quickly pulled from theaters after release, then disappeared for decades. In 2021, Jane recorded a new introduction for the Kino Lorber restoration and rerelease of the film, in which she notes that while the antiwar effort stateside was led largely by white, affluent Americans, the antiwar movement within the military consisted largely of non-white, working class troops who couldn't afford college deferment, making their protest far riskier. Her attempts to amplify their experiences coincided with her professional blacklisting: she became unemployable over her beliefs, as conservatives loudly decried her as a traitor to her country, simply for questioning the Nixon’s administration’s line on the war. Offscreen, she successfully sued the administration over violations of her civil liberties, conducted via a secretive campaign of illegal surveillance and harassment: the Feds opened her mail, embedded agents in her circle, and showed up at her daughter’s kindergarten. Named in her lawsuit were two banks—Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York (i.e. J.P. Morgan) and City National Bank of Los Angeles—both of which conspired, without her knowledge, to give detailed accounts of every single one of her financial transactions to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI released their files on her, and she dropped the lawsuit.

Her romance with second husband and “Chicago Seven” figure Tom Hayden, led to a concerted effort to soften her public image and cater to his emerging political aspirations; this, the end of the war, and the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974, cleared the way for her return to Hollywood. But to say that Fonda “sold out,” is something of an oversimplification: she simply held her cards that much closer to her chest. Sensing, with that keen eye of hers, yet another need for reinvention, she found a version of herself that could stand in positions of power while keeping her political convictions steadfast. She began her pop culture restoration with Fun with Dick and Jane (1977), an anticapitalist comedy classic about a bored, upper-middle class couple who take to a life of crime to fund the construction of their backyard pool. A major commercial success, Fonda levied this clout into Julia (1977), an adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s totally bullshit memoir about the time she definitely smuggled funds to the resistance under the eyes of Nazi Germany. Historical accuracy aside, it was a massive critical hit; Fonda earned an Oscar nomination, so she kept going. Forming her own production company, IPC Film, she made Coming Home (1978), a melodrama about an unhappily married housewife who begins a romance with a paraplegic veteran (Jon Voight, if you can believe it) while her husband (Bruce Dern) is away in Vietnam. Fonda funneled her own experiences and exchanges with veterans into the film, even fighting with director Hal Ashby over a penetrative sex scene that she had rewritten as a cunnilingus scene culminating in the female character’s first orgasm—a rarity for the time. For her efforts, Jane Fonda won her second Academy Award for Best Actress (she delivered her acceptance speech in ASL!), solidifying her return into the cinema firmament, a great middle finger to all the powerful men who tried to take her down—including the FBI, who, in addition to likely planting and fueling negative sentiment about her in the press, orchestrated a bogus arrest in 1970 for “drug trafficking.” In her iconic mug shot, Fonda, still in her Klute shag mullet, raised her fist in the Black Panther salute.

Fonda’s official “Fuck You” era is a beautiful thing: when The China Syndrome (1979), a film about a reporter (Fonda) who witnesses a concerning incident at a nuclear power plant and becomes a whistleblower on its shoddy security measures, opened, the nuclear power industry excoriated the film for fear-mongering. Twelve days later, a partial nuclear meltdown of a power plant in Harrisburg, PA sent radioactive materials into the surrounding environment in the worst accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history, which fueled concerns about the potential dangers and environmental effects of nuclear energy. Dubbed the “Three Mile Island” accident, the real-life disaster fueled the film’s success and relevancy, earning Fonda another Academy Award nomination. And when it came time to make a feminist workplace romp, Fonda got one over on her conservative critics by carefully threading the needle between screwball comedy and social satire of the 1930s: 9 to 5 (1980), a cultural Trojan horse that hides its labor antagonism behind a kicky Dolly Parton track, painting a fantastical misandrist tableau that makes a case for childcare, equal pay, sexual harassment education, and flexible hours for female employees.

Fonda took a lot of heat, once more, for the next phase of her celebrity—workout guru. In his documentary Hypernormalisation, documentarian Adam Curtis used footage from Fonda’s incredibly successful line of home workout tapes to illustrate the left’s abandonment of political values in the wake of the Vietnam War. Actually, proceeds from those tapes went directly to the Campaign for Economic Democracy— Tom Hayden’s PAC that promoted a slate of progressive causes, including rent control—as well as Fonda’s own political causes, like abortion rights and the fight against apartheid in South Africa. On a more personal note, Fonda credited the “workout,” as she termed it, with helping end her lifelong bulimia, which persisted through all her personal triumphs, losses, pregnancies, and activism; all the phases of Fonda’s life, really, marred by body dysmorphia. Developed out of her Los Angeles fitness studio, Fonda’s fitness empire, which included classes and an album, as well as, eventually, a series of home video workouts (beginning with Jane Fonda’s Workout, from 1982) fueled the VHS revolution, as women bought home video equipment en masse specifically to use the tapes. At the time, many gyms were only open to male bodybuilders, and Fonda’s tapes found and catered to an underserved market: women who, for whatever reason, didn’t feel comfortable stepping into a gym. Unlike the many, many imitators to follow, Fonda’s tapes are textually very interesting: set in her warm, inviting studio and populated by beautiful, lithe bodies, watching her workouts feels like getting into a cool dance class, where everyone’s doing Fosse-style moves to tighten up their glutes.

Jane Fonda formally retired in 1991 amidst her third marriage to media mogul Ted Turner, but it didn’t stick: she returned with a supporting turn in Jennifer Lopez vehicle Monster in Law (2005), to box office triumph that proved that at 68, Fonda was more beloved (and relevant) than ever before.5 She bore witness to the fall of Lindsay Lohan with Georgia Rule (2007), defending the increasingly beleaguered young star when a scathing letter from one of the film’s producers about her onset behavior was leaked to the press. Ironically, she played blowjob queen Nancy Reagan in the Weinstein Company’s Forrest Gump reheat, The Butler (2013), and drew critical acclaim (and a Golden Globe nomination) for her performance in Paolo Sorrentino’s showbiz dramedy Youth (2015). But really, the definitive work of her twilight era is Grace and Frankie (2015-2022). A universally beloved Netflix sitcom starring her friend and 9 to 5 co-star Lily Tomlin, the two living legends play polar opposites who live together and spend their lives at each others’ sides after their husbands reveal their long-standing affair with one another. It's a quietly groundbreaking show: these two women become each other’s life partners, navigating uncertainty together, but also living it up in a cute little house by the sea, never letting a revolving door of romantic and sexual partners upset their new arrangement.6 Hollywood depicts old age as a death sentence for women, but Grace and Frankie, which brought the stars a whole new generation of fans, defies that narrative, and the notion that we can sunset these living divas just because they’re old(er). When Fonda, at 81, opened a box office hit with romantic comedy/airplane movie classic Book Club (2018), it just proved that there’s a real appetite for stories concerning older women—if only Hollywood would give them a chance! Fonda, the rare celebrity to remain culturally relevant sixty years after their screen debut, is an industry icon, but she’s still fighting injustice: just put her name in a recent news search, and you’ll see the myriad ways she’s still lending her name and money to support causes she believes in. Famously, in October 2019, she spent four consecutive weeks protesting climate change outside the U.S. Capitol, each time ending in arrest. She’s still going; she’s still fighting. I’m getting emotional as I reflect on this—truly, there are low-key tears in my eyes—because at a time of such political uncertainty, there’s something so inspiring about a woman who could be resting on her laurels, but continues to give a shit, even as we’re told that giving a shit is hopeless or corny or both. Fonda made giving a shit cool—not because it was the fashionable thing to do, but because it’s the only way she could honestly live in the world.7

“What we, actors, create is empathy,” Fonda said in February, at the Screen Actors Guild Awards, where she received a lifetime achievement award. “Empathy is not weak or woke. By the way, woke just means you give a damn about other people.”

Continue Eating the Oysters or You Will be Shot and Killed: Maryland on Film

On December 1st, 1948, a young congressman named Richard Nixon called the FBI to report that Whittaker Chambers—the Time editor and alleged ex-Soviet spy currently testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee against former State Department official and alleged Soviet asset, Alger Hiss—now had tangible evidence to corroborate his outrageous claims about Hiss… an incredibly convenient and fortuitous development, given that Chambers spent years claiming no such evidence existed. Convening at Chambers’ Maryland farm, HUAC investigators were soon handed a roll of microfilm which had been stowed in a hollowed-out pumpkin hidden in his pumpkin patch. The roll contained smoking gun documents with Hiss’ handwriting, seemingly proving that he was part of a Communist spy ring. Based on this evidence, the so-called “Pumpkin Papers,” Hiss, who always maintained his innocence, was indicted for perjury, while Richard Nixon was catapulted into the national spotlight for the first time. What better illustrates the sheer absurdity of our political theater and the odd, indecorous quality of Maryland itself, than a bunch of stuffed shirts rummaging around a pumpkin patch, hunting for Commie Clues?

There’s just something about the state of Maryland, that tiny smattering of land that’s the seat of the nation’s power, surrounded in all directions by rural brush and coastal enclaves, that makes it so ripe for intrigue. Founded as a haven for persecuted English Catholics, the state, well-situated on the Chesapeake Bay, sits squarely in the middle of the nation and feels pulled between its two never-reconciled halves: during the Civil War, it remained in the Union, even while slavery remained legal in the state (as a border state, it was not included in the Emancipation Proclamation and slavery was not made illegal until a new state constitution in 1864). The garish state flag is quite literally a clash between the two battle flags employed by Marylanders who fought for the Union and the Confederacy, derived from the coats of arms of the Calvert and Crossland families, respectively. That schism engenders a state culture that never quite seems to gel: rednecks and white collar civil servants; segregation and ethnic diversity; the rural expanses of the Appalachian Mountains out west and the coastal lowlands of the Eastern Shore, contrasting with the dense urban centers stuck in the middle along the Piedmont Plateau. “America in Miniature” they say—and water, water, everywhere.

It’s just that kind of too-close proximity between urbanity and provinciality that explains how a bunch of queer punks could stage a freak show in the woods, in which local hicks gawk in disgust at gay sex acts, or copulate with a bunch of chickens in a trailer on an unincorporated swath of land outside of Baltimore. Which is just what John Waters and his Dreamlanders—a collective of local friends and actors—did with Multiple Maniacs (1970) and Pink Flamingos (1972), respectively; the latter of which became one of the most infamous cult films of its time and made the filmmaker a pioneering figure in American independent film. Inspired by his love of tacky movies, watched at the local drive-in, Waters, the product—like so many Maryland creatives—of private Catholic school education that didn’t quite take, brought a queer lens to mainstream American culture, satirizing middle-class morality from typically unremarkable locales.8

“I hate the Supreme Court!” Mink Stole screams at a bunch of children playing baseball in the yard of a wealthy Baltimore suburb in Desperate Living (1977), before killing her husband and absconding with her maid to a rural enclave, run by militant lesbians. “Will you please stop it?” she whines to a cop with a deep Maryland accent and a fetish for wearing women’s underwear after they’re quickly pulled over on the highway. “I have never found the antics of deviants to be one bit amusing!”

In his later, more accessible films, Waters dramatized his own experiences growing up in Baltimore—including the working-class “drape culture” and the segregation of the 1950s and 60s—as a sort of bizarre love letter to the freaks that thrived, and kept the city weird, against a backdrop of racists and rubes. In the process, he gave voice—and what a voice, that flat, wide “O” vowel that I hear, every day, from my own beloved husband’s mouth—to a bizarre little part of the world that’s been the subject of so much media relative to its square footage. In his 2005 memoir Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste, the filmmaker writes, “It’s as if every eccentric in the South decided to move north, ran out of gas in Baltimore, and decided to stay.”

All of John Waters’ films are included in this program, though he’s far from the only proud native son of Baltimore canonized here: also represented are the films of Barry Levinson, like Diner (1982)—which stars Ellen Barkin, a woman his son, Euphoria creator Sam Levinson, born three years after this film, would later date—Avalon (1990), and Liberty Heights (1999), developed out of the acclaimed writer/director’s family history, as well as his own experiences growing up Jewish in the 1950s Baltimore suburbs. Plus, two pioneering series set and shot in Baltimore from David Simon, former writer for the Baltimore Sun turned self-serious television scribe: Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-1999) and its spiritual successor, The Wire (2002-2008), regarded as two of the greatest television shows of all time, both notable for expanding the artistic possibilities of television filmmaking, complicating the “cop procedural” format, and using the fabric of Baltimore itself to enrich their stories. The Wire in particular presents Baltimore as the dark mirror image of Washington D.C.: a city in which citizens are underserved by institutions marred by corruption, underfunding, and the chaos of poverty and racial disenfranchisement, in which bad deeds are done by all sides, but only some are afforded protection. But, you know, with pit beef and funny little voices. “It’s Baltimore, gentlemen,” Deputy Commissioner Ervin Burrell (Frankie Faison) taunts a mob of cops. “The gods will not save you!”

Beyond urban Baltimore, we journey into the leafy environs of the surrounding state, with films like Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964), a psychosexual melodrama set at Chestnut Lodge, a real-life private mental institution in Rockville that has since been demolished and turned into a local park. In Lilith, the patients, including Jean Seberg, a young woman living with schizophrenia, roam the grounds and wild terrain abutting the hospital, antagonized by its wild natural spirit. The film even includes a woodsy sequence set at a “jousting” tournament, which is a real-life activity in which riders lance poles through hung rings (this is, believe it or not, the state sport of Maryland). I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (1977), based on a semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, also draws inspiration from Chestnut Lodge. Cult indie horror filmmaker and zine writer Don Dohler shot his low-budget horror movies like Fiend (1980) and Nightbeast (1982)—which a 16-year old J.J. Abrams actually worked on—in the wooded suburbs around Baltimore. And the most successful indie horror film of all time, The Blair Witch Project (1999), makes memorable use of Maryland’s densely forested state parks to stage a deeply upsetting tale of Hiking Gone Wrong. Set in Burkittsville—a historic village in Frederick County—and shot primarily in Seneca Creek State Park in Montgomery County, the film’s chilling climax even unfurls in the super-creepy (and since-demolished) Griggs House, located in Patapsco Valley State Park…far more sinister than it has any right to be.

There’s a deep rot in this culture—maybe it’s the Catholicism; maybe it’s the extra strength it takes to crack open all those crabs; maybe it’s all the environmental pollutants absorbed into the skin at Seacrets—that engenders such satisfyingly upsetting art.

You’ll find so many varied aspects of Maryland culture represented in this program: its intense religiosity (Saved!); the D.C. area’s influential hardcore punk scene (Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980–90), and the suburban heavy metal crowds of Heavy Metal Parking Lot); the heavy concentration of industries like the media (All the President's Men, Broadcast News, Shattered Glass), the military (Shipmates Forever, Annapolis), and intelligence (Patriot Games, Enemy of the State, Red Dragon); and the area’s rolling farmland (Pollyanna, The Mating Game). If you know that “Take Me Home, Country Roads” was actually inspired by a drive down Clopper Road in Montgomery County, this program is for you.

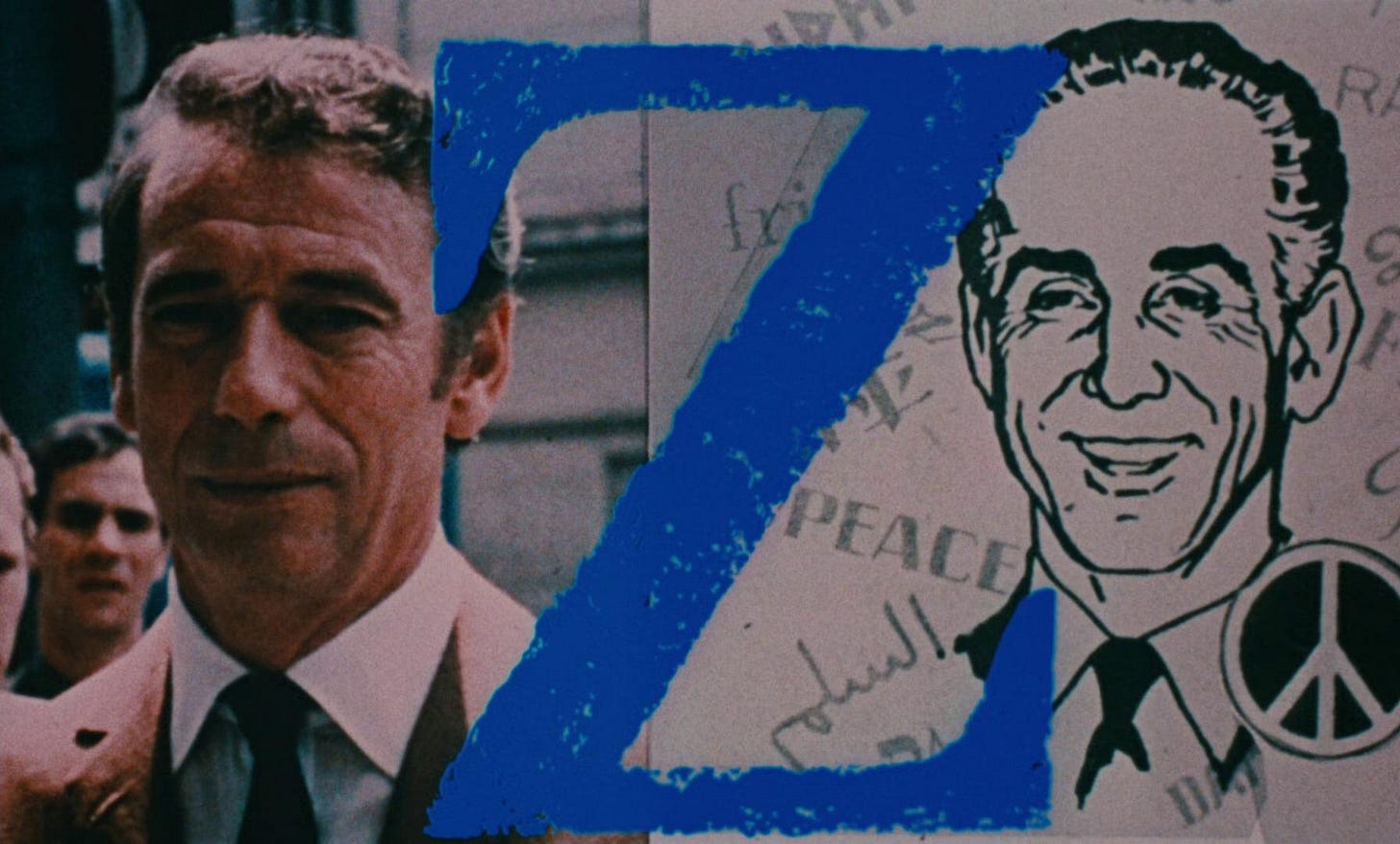

Plus: Leftist Cinema from A to ”Z”

This annual program features our continually expanding list of international progressive cinema with updated streaming and access information, ready for your enjoyment. Recent additions include last year’s phenomenal Nickel Boys (2024), Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat (2024), and the Academy Award-winning documentary No Other Land (2024), as well as a bunch of influential Palestinian films like Fertile Memory (1981), Intifada: Road to Freedom (1988), Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996), Jenin, Jenin (2002), and 5 Broken Cameras (2013).

I’ll leave you this month with the immortal words of Eugene Debs, which bolster me in days like these, when I feel closest to despair: “While there is a lower class, I am in it, while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

That’s all for May! Until next time, keep looking up: every word we need comes from the skies, can't you read my eyes saying love?

All of these Hoover Facts come courtesy Beverly Gage’s G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (2022), a must-read.

The film’s shooting script goes further in its use of Masonic symbolism, including an unused scene of Hale and his fellow masons—including a man later revealed to be part of the local Ku Klux Klan—performing the Scottish Rite ritual of “Extinguishing the Tapers.”

You Must Remember This has an incredible episode on John Garfield as part of their 2016 series on the Hollywood Blacklist, a reference for this program.

Things got so bad they’d literally be arguing back and forth in the press. Eventually they mended their fractured relationship, at least enough to make On Golden Pond (1981), a film Fonda conceived as a bid to win her legendary father a long-denied Academy Award (it worked, but he was too sick to attend the ceremony). She played his onscreen, estranged daughter, a melancholy echo of their own dynamic.

Whatever her offscreen relationship with JLO, it was solid enough to facilitate an incredibly game appearance by Fonda in the singer’s maligned Amazon Prime music film This Is Me... Now: A Love Story (2024), in which she plays a member of the “Zodiac Council,” looking down on JLO’s poor life choices.

I’ll never forget an episode in which the pair are confined to a nursing home against their will and have an existential crisis when they realize that they’ll never be allowed to cook in their own space again. But the show’s frankness is also…empowering. Demystifying. Oddly…soothing?

The 2017 You Must Remember This series “Jean and Jane,” a major resource for this program, compares and contrasts the lives and careers of Jane Fonda and fellow actress activist Jean Seberg.

While making his first feature, Mondo Trasho (1969), John Waters and crew were arrested for shooting a sequence of a naked man walking on the campus of John Hopkins University.